Fatima Mernissi, Morocco’s Feminist Icon

This is a guest post from Ausma Zehanat Khan. Ausma holds a Ph.D. in international human rights law. She is a former adjunct law professor and was editor in chief of Muslim Girl magazine, the first magazine targeted to young Muslim women. A British-born Canadian, Khan now lives in Colorado with her husband. The Language of Secrets is her second novel, following The Unquiet Dead. She is currently at work on her third mystery in the series. Follow her on Twitter @Ausmazehanat.

When I was an undergraduate, two books were all the rage in the circles I moved in: Fatima Mernissi’s Beyond the Veil, and her feminist tour de force, The Veil and the Male Elite. Fatima was a sociologist who examined the relationship between women and the Qur’an, women and men, and women and the caliphate, subjecting each to meticulous inquiry. Because she was a critic of the status quo, namely the entrenched idea that men were entitled to moral and religious superiority, her books sparked a great deal of debate—much of it hostile. When she came to speak at my campus, a delegation of young Canadian Muslims was sent to interrogate her point of view.

I was a member of that contingent, and of course I knew nothing about the exacting standards of scholarship, or the rigorous process by which Fatima had re-examined history and scripture. But I had read both her books and was eager to hear her speak. When I saw her in person—a vibrant, confident woman, very much at her ease, speaking with elegance and humor, I knew her talk was about to change my life.

Fatima was the first feminist scholar of Islam I encountered. She wrote from within the tradition, as a believer in the absolute equality of men and women. The Veil and the Male Elite was a ground-breaking work, a thorough and patient examination of the sources used to enforce the submission of Muslim women, where Fatima took arguments advanced by the religious patriarchy in favor of men’s superiority, and exposed them as outright fallacies. In the words of her obituary in The Guardian newspaper, “Fatima connected the degradation of woman to man, and man to the imam and the caliph.”

So much of Fatima’s work was about freedom of thought. the autonomy of the individual, and the right to interrogate tradition using reason and free will. Her knowledge of the Qur’an and the intellectual strength of her logic inspired generations of women, including myself. I fell in love with her sense of autonomy: I was always inside the Islamic tradition but now I could speak with authority and be heard.

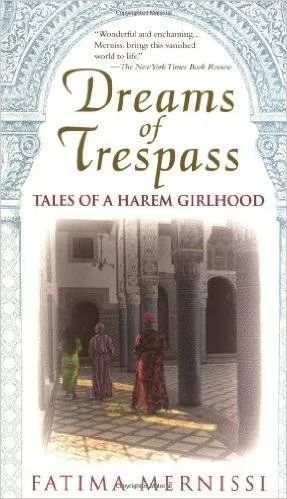

Fatima’s memoir was so lyrical, so effortlessly graceful, so intimately expressive, that it taught me to look at myself and the lives of all the Muslim women I knew with much greater consideration and empathy. It was my first experience of solidarity.

Fatima’s sparkling intellect will be missed but her powerful legacy lives on.

- The Women in Science We Don’t Write About

- Terry Tempest Williams on Women and Books

- Feminist-Friendly Comic Books

- Lauren Beukes On Writers and Their Cats

- Sonali Dev on Why She Writes The Heroines She Writes

- All Around the World: Women Writers from Every Continent

- On Worldviews and Reading Widely

- 50 of the Best Heroines from Middle Grade Books

- Between Worlds: Finding Home in Fantasy