8 Writers Discuss How Fairytales Can Disrupt The Status Quo

A fairytale provides the form and basic building blocks a narrative can take, but the storyteller adds the meaning, chooses what to include and exclude, what to emphasize and what to make backstory. Fairytales reflect the social norms of the teller, which includes the time period they live in, their culture, their religion, etc. Since most fairytales stem from patriarchal societies, older versions are full of sexist and racist values. But modern retellers can change that, can transform a tale to reflect different social values, can push back against societal constraints. The familiarity of fairytales makes them the perfect receptacle for disruption. Readers will notice any slight change, any shift in the narrative, and a world of meaning can be put into those changes.

Take, for example, Beauty and the Beast, originally written by Gabrielle-Suzanne Barbot de Villeneuve and published in 1740, then popularized by Jeanne-Marie Leprince de Beaumont a decade later. Beaumont adapted Villeneuve’s version by shortening it and including more virtue signaling. Both pieces have predecessors, of course, in the myth of “Cupid and Psyche” as well as older fairytales featuring animal transformations and marriages. In Beauty and the Beast: Classic Tales About Animal Brides and Grooms from Around the World, Dr. Maria Tatar explains some of the social contexts Beaumont put into her retelling: “Madame de Beaumont’s tale attempted to steady the fears of young women, to reconcile them to the custom of arranged marriages, and to brace them for an alliance that required effacing their own desires and submitting to the will of a ‘monster.’” When I taught fairytales several years ago, my college students were shocked to think about Beauty and the Beast as a tale about arranged marriages. For them, the story is about loving people no matter what they look like, and while they’re not exactly wrong, they’re failing to think about how young girls were often married to much older men, men they would perhaps find beastly. It’s also notable that Beauty is, well, beautiful. Would the story be the same if she were as hideous as the Beast, or if their places in the story were exchanged?

Centuries later, in 1979, Angela Carter published “The Tiger’s Bride” in The Bloody Chamber and Other Stories. In this retelling, Beauty’s father gambles her away in a game of cards to a beast. At the end of the story, Beauty allows her tiger husband to lick away her skin and reveal her animal pelt. Carter, writing during the sexual revolution, used the frame story of Beauty and the Beast as a way to embrace women’s sexuality and animal instincts.

Anytime a writer retells a fairytale, they’re putting aspects of their culture and social values into the piece, whether intentional or not. I spoke to eight contemporary fairytale retellers and asked about their thoughts on how fairytales reflect social norms, and what changes they made to fairytales in their own retellings to reflect their societal values.

Poisoned Author Jennifer Donnelly

“Fairytales are like Rorschach tests, and what we see in them speaks to different needs we have as we grow and age. The ideas for Stepsister and Poisoned are not so much these bolt-of-lightning type things that come to me; they’re more driven by unanswered questions I’ve had since I was little. For some reason, these questions are demanding answers now. For Stepsister, I wanted to know who decided that the stepsisters were ugly. Why do we let that person decide? And is it time, maybe, that we decided for ourselves?…

What’s a bit puzzling to me is why now—why are these questions I’d buried deep long ago surfacing now? I’m not entirely sure, but I think it’s because I’m watching my own teenage daughter and her friends try to navigate their way through a world that still too-often judges girls not by their abilities or achievements, but by their looks. And I think it’s also because of the seismic shift our society is going through with regard to the #MeToo movement. That has made me question a lot of things I didn’t even know I could question, and imagine changes to our world that were once inconceivable to me. If my books could be even a small part of the feminist conversation, if they could prompt young readers to ask questions of themselves and their world—that would make me very happy.”

Vicious Spirits Author Kat Cho

“The one thing that really struck me about the gumiho myth is how it’s always about how the female fox is evil and only motivated by evil desires. However, some of the oldest/first fox spirit myths do depict the fox spirit as benevolent and even helpful (for example, there’s one where a fox spirit helps a monk find enlightenment). I wanted to unpack how it could come about that the gumiho would only be depicted as evil and explore the idea that the men who told stories of this female fox might have had ulterior motives for blaming everything on the female fox. Then, when I added the concept that the gumiho is real (I mean, what? They’re definitely real…) how would that affect how a gumiho would see herself if everyone believes she is evil.”

Bookish and the Beast Author Ashley Poston

“I love subverting tropes. Most retellings are very much rooted in misogyny, even though now (mostly because of Disney) they are used to inspire young girls to go out and chase their dreams. In Geekerella, for instance, the original fairytale has Cinderella finding her Happily Ever After through the foil of a prince. It’s through him she can go on to live how she wants, and so when I was adapting it, I wanted to change that. Cinderella would save herself. For Bookish and the Beast, I had to treat the fairytale a little differently. As you said, it began as a story written to prepare young girls for arranged marriages, but it hasn’t aged very well at all. So I began with what people today still love about the fairytale—Beauty’s gumption, her kind heart, her loving relationship with her family—and decided to rebuild the fairytale from there. So it’s less about Beauty being the victim of circumstance, but Beauty creating her own circumstances, like I did with Cinderella. I am a deep proponent of princesses saving themselves, and trust in relationships being earned instead of given, and I hope that comes through in my stories!”

The Mermaid, the Witch, and the Sea Author Maggie Tokuda-Hall

“I think one of the most central aspects of fairytales is ‘getting the girl,’ which is a gendered and heteronormative tradition I find a little wearying. So when I sat down to write my own fantasy novel that would have that kind of grand scale, fairytale feeling, I wanted to give new lovers a chance to find each other on a stage set with witches and mermaids and magic and mayhem. And so I have Florian or Flora, who is a genderfluid pirate, and Evelyn, who is a cis lesbian at the center of my tale. I think fairytale-like stories are a perfect place to explore ideas of shifting identities and sexuality, because we know the shape of the stories already. Allowing new, more complicated characters to stand in the place of those we already know adds a layer of delight in creation for me, and I hope readers enjoy it, too.”

Star Daughter Author Shveta Thakrar

“[O]ne thing I love about ‘Savitri and Satyavan’ is how it can be viewed through a feminist lens—Savitri chooses her own husband and then must save him from Lord Yama (Hindu god of death) by using her wits.

With Star Daughter, it’s a little more complicated. I adapted the source material (Vedic astrology), peppered in bits of mythology here and there (like the story of Gajendra and the Crocodile), and even made up my own myth (the creation of diamonds) to create what I think is a modern and feminist original fairytale. Though half star, protagonist Sheetal is also half human and was born and raised in America, and I wanted that to come through. After all, I’m diaspora myself, and shaped for better or for worse by the culture and time period I grew up in!”

Girl, Serpent, Thorn Author Melissa Bashardoust

“Much of Girl, Serpent, Thorn was inspired by ‘Sleeping Beauty.’ Some of the earlier versions of ‘Sleeping Beauty’ are very disturbing in terms of consent and agency, and while the more well-known versions remove or soften some of the upsetting details, there is still that question of the main character’s agency. That was something I knew I’d have to deal with in working with ‘Sleeping Beauty’—how do you give a character agency when she spends most of the fairytale asleep? My way of reframing that story was to look at each of its pieces symbolically—what does it mean to touch the spindle, what does it mean to be asleep, and what does it mean to awaken? So while Girl, Serpent, Thorn is different in terms of the plot details and the characterization, I was looking at the same themes and questions that the original stories stirred in me—but my answers to those questions are based on my own modern-day values.

As for the Shahnameh, the context is interesting because the Shahnameh was written at a very specific moment in time and is itself a recontextualization of earlier myths and cosmological beliefs. While there is much scholarship regarding the Shahnameh and its background and I’m certainly not an expert on the nuances there, the commonly accepted interpretation is that its author was trying to preserve a cultural identity, and especially language, that was under threat of being forgotten or replaced at that time. I’ve tried to be mindful of that context while writing this book, and have been inspired not just by the world and characters of the Shahnameh but by the earlier myths and beliefs that it transformed. But I’m also drawing on broader themes and elements in some of these stories, like complicated family dynamics, the need for belonging, or the fear of becoming a monster.”

The Once and Future Witches (October 13) Author Alix E. Harrow

When I spoke to Harrow, we discussed her series of fractured fairytale novellas forthcoming in 2021.

“That’s the secret superpower of retelling stories again and again and again! They’re never the same story, really, because we’re never the same tellers or listeners. (It’s popular to complain about remakes and retellings of popular franchises, but I’m fascinated by all their endless iterations).

And yes, I chose ‘Sleeping Beauty’ precisely because its origins are so profoundly bleak (Google ‘Sun, Moon, and Talia,’ folks), but also because it’s so difficult to rehabilitate. Even removing the original element of assault on a sleeping woman leaves you with a painfully passive protagonist, a princess-shaped object who is cursed and then un-cursed entirely without her own involvement.

I don’t want to spoil my own as-yet-unwritten book, but I hope I can find a way to give the Beauties the agency their own stories deny them. And I think when you put lots of disempowered people together, they become…not so disempowered, after all.”

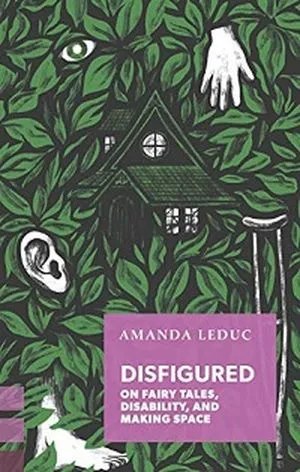

Disfigured: On Fairy Tales, Disability, and Making Space Author Amanda Leduc

On why while many modern retellings depict today’s feminism, more characters of color, and more LGBTQ+ characters, disability representation still tends to depict the same negative stereotypes:

“One of the biggest reasons for this, I believe, is our tendency—especially in our Western, ‘Disney-fied’ culture—to lean toward the idea that fairytales end happily, even though historically that has been far from the case. (You need only look at some of the more obscure Grimms’ tales to understand that happy endings do NOT always come to everybody.) There is still very much an entrenched idea in today’s society that disability is incompatible with the idea of a happy ending, and when you put that together with the (also firmly entrenched) idea of a fairytale as having to have a happy ending at all costs, it becomes difficult for many people to imagine a world in which these two things—fairytales and disabled happy endings—can exist together. So in order for a happy ending to come about in a fairytale, disability needs to be eradicated in some way.

I think it’s also worth noting that many people still conceive of fairytales as existing in a pre-technological, pre-industrial society. Historically, these types of societies were never built with the disabled body in mind, or took the disabled body and life into account in any way. So the transformations that occur in fairytales have necessarily had to happen on the individual level, because it was almost impossible for the writers of original fairy tales to imagine a transformation that happened on the level of society. Thus, it is easier to imagine a transformation where a half-human hedgehog boy turns into a man than it is to imagine a society that transforms to recognize the hedgehog boy for who he is.

This is, of course, rather ironic when you take into account the fact that magic is rampant in fairy tales—surely Cinderella’s fairy godmother could just as easily have used her magic to overturn the social order!”

To read more about disability representation in fairytales, check out my discussion of Amanda Leduc’s memoir in conjunction with an analysis of The Witcher and Pet by Akwaeke Emezi. Here are some of my LGBTQ+ fairytale recommendations, and some thoughts on why the same fairytales are told again and again and the problems with the white colonialist fairytale tradition. This look into how Nazis used fairytales to further their political agenda is disturbing and fascinating, and shows how storytellers can use fairytales to reflect their values in sinister ways.