The Importance of Pandemic Diaries

It has never been quite so clear to me that I am living through a Major Historical Event that will end up in future history textbooks. There might even have to be a full three pages on 2020 in the updated version of the U.S. History textbook I remember from 11th grade. The type in that textbook was infinitesimal, and there were three columns per page, so three pages would be a lot.

Your history teacher may lecture you about primary sources, and they’re right to do so. First-person accounts of major historical events help us live in the moment and understand more of the day-to-day. Ruth Franklin tweeted early on, before major lockdown measures, to encourage people to start writing diaries and reflect on what was happening around us. Jen Miller at the New York Times also took up this idea and expanded further about why it was helpful and necessary. Diaries were not only a way to reflect and process your feelings but could be extremely precious as archival accounts in the future. It’s not about writing the perfect, most interesting account, but communicating the reality of what’s happening. Wright State University put together a series of prompts to help us get started.

Plagues Throughout History

When we look into historical, first-person accounts, we’re usually looking for something profoundly illustrative of the time. What we usually get is a much more nuanced, quotidian account. Samuel Pepys, a Member of Parliament in the 1670s in England and later a naval administrator, kept a diary from 1660 to 1669 that coincided with the Great Plague of London, the Second Dutch War, and the Great Fire of London. He catalogued the day to day as much as the life-changing events, which makes his diaries such a useful source for reconstructing that particular period in history. His tracking of the Great Fire of London of 1666 helped historians track down exactly how the fire started and spread so aggressively throughout the city. Some have pointed out that his cataloguing of the Bubonic plague felt similar to the experience of the coronavirus pandemic. Diarist accounts of plagues have been extremely helpful to historians throughout history: a historian named Paolo Guerrini documented the plague in Brescia of 1478 in Italy, and there is a similar diary from Absalon Pederssøn about the 1565–’67 plague of Bergen in Norway. Notably, the plague in Bergen came from a ship bound from Danzig. There were many instances of the bubonic plague throughout history, and we’ve been able to reconstruct the effects and deadliness on the day-to-day lives of people at the time through these diarists.

In the United States, the closest moment geographically was of course the influenza outbreak of 1918, which had its own series of diaries documenting the disease. Diaries about the coronavirus/COVID-19 have quickly cropped up in news publications—CNN has their own tag for the necessary documentation of the work. Slate has recently pivoted to people dealing with the reopening fracas. We’re also relying on healthcare workers (doctors, paramedics, and more first responders) to keep video and written diaries to give us the tangible effects of the disease in the world of hospitals. The first-person accounts are not only providing a historical record for future archivists, but also a needed form of connection between all of us sheltering in place (or going out and about, as states start to re-open and then have to close down again because people aren’t practicing smart and safe public behavior). We also relied on stories from Italy and China early on to give us a window into what the U.S. would be like under lockdown.

Living Through Oppression

Living Through Oppression

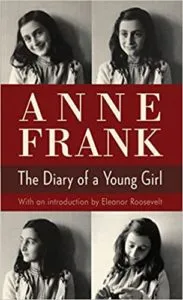

In the time of war, first-person accounts are necessary to save and show the human toll, especially when major world powers attempt to censor and hide the experience of suffering. I think we currently take Anne Frank: The Diary of a Young Girl for granted—Otto Frank initially only published it in the Netherlands. It was a huge success and continued moving around the rest of the world because it laid bare the intense tragedy of World War II on the Jewish people who were forced to go into hiding to avoid camps and death.

In a similar fashion, wartime doctor Dang Thuy Tram kept a diary of her experiences fighting the U.S. troops away from her field hospital in Vietnam. Last Night I Dreamed of Peace didn’t come out until 35 years after the fact—the story of its publication is fraught as well. It is tangible proof that the dissemination of the experience of the oppressed is an important political act.

At the same time as the pandemic rages on, the Black Lives Matter movement has gained global traction with protests cropping up around the world, taking down racist statues and demanding equal rights. First-person accounts are how people are organizing, especially over social media. In a turn of events that will stun no one who has followed teen activism, many young people are organizing protests across the U.S.

Archival Activism

There will be narratives of people trying to change and reform the way the protests and the pandemic functioned in the United States, especially when textbooks edit history and gloss over difficult topics. Activists suggest saving articles that lay out the facts of police brutality at protests and the experiences of protests on archive.org to make sure they live on the Internet. A devoted archivist could also start saving as many articles as possible—this is a time of constant first-person accounts because there is so much wild misinformation.

Archives are not stable, impersonal creations. They rely on people who care about the preservation of history to exist. The current moment needs both documentation and preservation, especially with regard to the pandemic because the current U.S. government wants to present a vastly different narrative about the coronavirus than the lived experience. They are also constantly lying about the protestors. First-person accounts will be necessary to tell the real story of the uprising and the pandemic years down the line, especially to show our future generations that we did not take this experience lying down.

There are plenty more first-person accounts and memoirs to dive into about war, contemporary experiences, or politics for research on major historical moments.

Living Through Oppression

Living Through Oppression