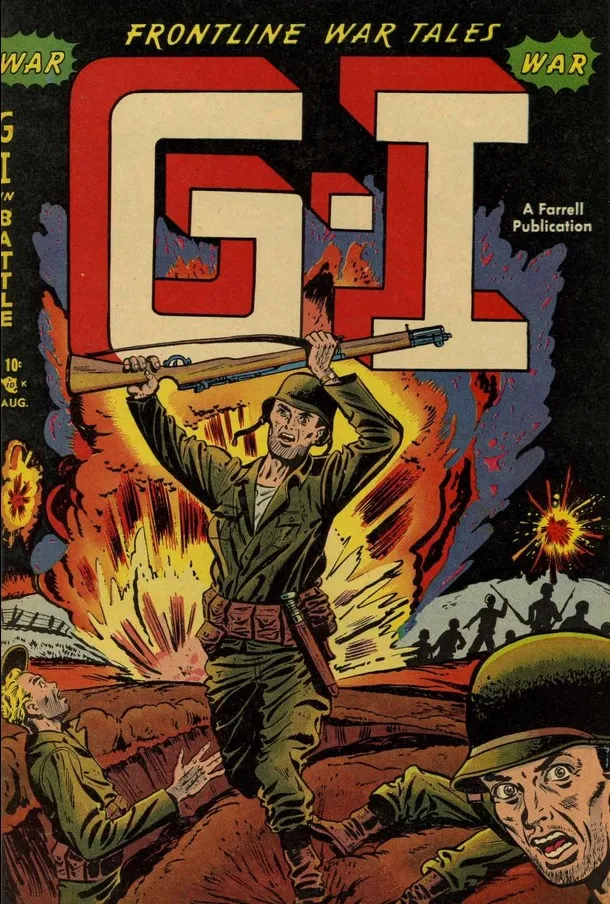

Retro Comic Rewind: G-I in Battle

Some comics go down in history as masterful examples of the craft and are beloved by multiple generations. Others end up at the landfill. In this series, I’ll be looking back on some forgotten series to better understand what kind of comics our ancestral nerds were reading in the days of rotary phones and record players.

Today’s subject: G-I in Battle!

The Context

The Korean War began in June 1950 when North Korea invaded South Korea. The U.S. and the UN quickly got involved on the South Korean side, which led China to send in troops and the Soviet Union to provide support and supplies to the North. Everyone thought the war would end fast, which of course means it slogged on for years longer than they expected. Both sides signed an armistice in 1953, but the war still hasn’t ended.

G-I in Battle was first published in 1952, which seems like a funny time to debut a Korean War comic: by this point, it was clear the war was going badly, and most Americans wanted out. But I guess if your target audience is war-hungry little boys eager for exciting stories, that reality wouldn’t matter much.

As for the context of this article, I just got through reading Charles J. Hanley’s Pultizer-winning account of the Korean War, Ghost Flames. I figured there was no better time to review a Korean War comic than when that book was fresh in my memory.

The Creators

Farrell Publications were at the height of their popularity in 1952-53, when they published G-I in Battle. However, it wasn’t the war comics that gave them such a boost: it was their horror comics. Unfortunately for them, they were compelled to cancel all of their horror titles in the middle of the decade when the U.S. Senate came after horror comics for excessive gore. Farrell went under in 1958.

As for the writers and artists who worked on this title, I couldn’t find a thing. Just as well: the writing and the art are both pretty foul.

The Comic

The first issue is the worst war comic I have ever laid eyes on. (Not that I’m an expert, but I’ve read a few for a past article, and when I say Yikes, I mean it.) The dialogue is ridiculously expository even for this era, and the plots defy belief. One features a soldier’s girlfriend who is actually a spy and lures his troop into a quicksand trap. They are rescued by a native chief who can speak to animals and gets his gorilla pals to pull the troop to safety.

After that, the series improves somewhat by removing the more unbelievable plot elements and the worst writing, and by sticking with your typical type of war stories. Unfortunately, “typical” for a war comic of this era is still pretty heinous.

Two stories feature characters — both medics, one a conscientious objector — whose job is to heal. But after watching North Koreans kill someone they cared about (either personally or professionally), the characters decide all Reds are “pigs,” drop their morals, and start killing.

I’m sure there’s an interesting story that could be told with such a scenario, but this ain’t it: the comic makes it clear that anyone who shows mercy towards the enemy is a sap, and the only reasonable course of action is wanton death and destruction.

The writers couldn’t have known this, but the Americans were just as murderous as their enemies. It was official policy for them to shoot indiscriminately at all refugees, just in case Northern infiltrators were hiding in their midst.

On a totally unrelated note, remember when Republicans didn’t want to let in refugees from certain countries in case there were terrorists among them? It’s almost like that entire line of reasoning is racist garbage!

As you may imagine, racism is rampant throughout this series. It took two sentences for them to start spouting racial slurs. I was expecting it — I don’t think there’s a vintage war comic in existence without racial slurs — but two sentences? Really?

(This is, unfortunately, historically accurate: U.S. troops had little to no respect for Koreans, even the civilians they were allegedly there to save.)

The best moment comes in Issue 7, where a Foreign Legionnaire is dragged into Korea and laments having to leave his “nice clean little war” in Vietnam to join the Korean police action.

The war he’s talking about is the First Indochina War, in which the French lost control of Vietnam, one of their colonies, and in which America became involved in that country for the first time. This led into the Vietnam War, which of course ended even worse for America than did the Korean War.

I don’t know if the writer was being sincere, or if they knew what was going on and slipped in some sarcasm. “Nice clean little war” indeed!

The series ended in 1953, not long before the war itself ended. Farrell revived the series as G.I. in Battle (note the punctuation difference) for six issues in 1957-58. Even though it’s just reprints of stories from Farrell’s previous war comics, the revival is more tolerable than the original: the stories tend to focus on relationships between individual soldiers rather than fighting the enemy. They even got rid of the racial slurs, replacing them with the more generic “reds” or “commies.”

Here’s a striking example: in G-I #9, this panel had an American soldier laughing after killing several soldiers with grenades. (Classy.) In G.I. #1, his dialogue has changed so that he’s just kind of looking around.

I’d like to think this change occurred because the publisher realized that racism is bad. But it’s probably because the Comics Code Authority, which banned “excessive violence” and “attack[s] on any…racial group,” was enacted in the interim.

The Legacy

Americans often describe the Korean War as “the Forgotten War,” because it tends to get lost between the longer conflicts (World War II and Vietnam) that flank it. Neither the Korean War nor the long-term damage it inflicted deserve to be forgotten. Nor should we forget the propaganda created in that war’s name, as it was just as insidious as any created for the “flashier” wars.

As I’ve discussed before, propaganda is not inherently bad. It’s a useful tool for educating people about new concepts. The problem comes when creators resort to lies and biased storytelling to trick people into agreeing with their perspective.

G-I in Battle falls firmly in the “lies and bias” category. It was sickening to watch American soldiers depicted as virtuous champions of democracy, all the while knowing that the real people they represented were committing the same inexcusable atrocities as their enemies. This is insulting to everyone, even the American troops themselves. According to Hanley, “psychiatric casualties” among U.S. troops were ridiculously high, with “as many as one in four men calculated on an annual basis” struggling mentally due to the brutality of the war.

Obviously, this does not justify their actions. But it also shows that they weren’t all bloodthirsty warmongers happy to slaughter every “Red” they came across.

Meanwhile, the one time G.I. featured a soldier with PTSD (in Issue 6), their “cure” was “kill more commies.”

Long story short: maybe you can salvage something from this if you like war stories, especially if you stick with G.I. in Battle rather than G-I in Battle. But for me, this was plain old unpleasant.

Want more vintage goodness? Check out previous editions of RCR: Race for the Moon, Stamps Comics, Tippy Teen, Winnie Winkle, and Hangman Comics!