Retro Comic Rewind: Race for the Moon

Some comics go down in history as masterful examples of the craft and are beloved by multiple generations. Others end up at the landfill. In this series, I’ll be looking back on some forgotten series to better understand what kind of comics our ancestral nerds were reading in the days of rotary phones and record players.

My first subject: Race for the Moon!

The Context

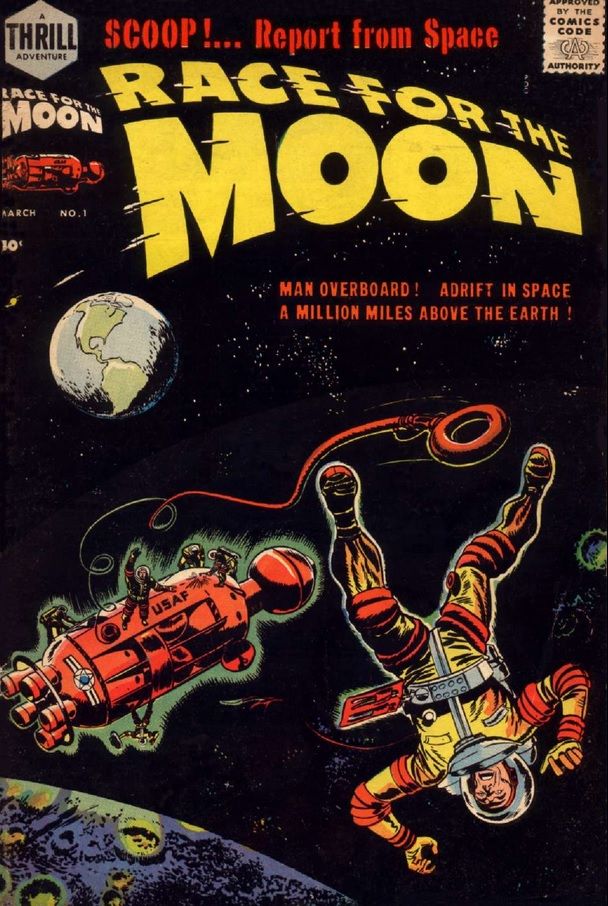

Race for the Moon ran for three issues in 1958. If you’re unfamiliar with history, the first page fills you in: the year prior, the Soviets launched Sputnik, the first-ever artificial satellite. America was so shocked and horrified by this development that they rushed to launch their own satellite, Explorer, in January 1958. Thus the “space race” began: not because two nations were invested in scientific discovery, but because they were desperate to win ideological points in the ongoing Cold War.

Americans became obsessed with space. This comic represents a small part of that obsession. The in-magazine ads even bill it as “the first space magazine of the space age!”

Knowing all of that, and going by the cover of Issue 1, I expected this series would include relatively grounded (so to speak) stories about American ingenuity and heroism as they sought to conquer space.

It does not.

The Creators

With older comics, it’s often hard to identify the book’s creators, and I definitely ran into a lot of question marks. But there are some big names ahead of those question marks in this case: Bob Powell, Fred Kida, John Severin, and, biggest of all, Joe Simon and Jack Kirby. All of them would go on to do important work for Marvel, and Simon and Kirby had already made their mark as the creators of Captain America.

Kirby’s influence was most obvious in Issue 3. Look at these panels and tell me that doesn’t look like Steve Rogers getting the super-soldier serum.

Kirby’s fingerprints are all over the storytelling, too. In “Garden of Eden” from that same issue, three explorers encounter a living planet, presaging his co-creation of Ego the Living Planet in Thor #132 eight years later.

According to Mark Evanier’s biography Kirby: King of Comics, Joe Simon was hired by publisher Harvey Comics first, as an editor. These being lean years for comics creators thanks to a growing anti-comics movement, Simon would sometimes try to secure work for Kirby, including in Race for the Moon.

Unfortunately, even these titanic talents couldn’t keep the title going for more than three issues.

The Comic

Most of the stories are hard sci-fi, taking place in a future where humanity (read: America) has already conquered the skies. A disturbing number of them involve using space as a prison, while others have ironic or twist endings meant to say something about human nature. In one very telling story (“Supreme Penalty,” Issue 1), a scientist goes rogue to try to convince his superstitious, earthbound superiors that “coloniz[ing] the universe” is the only way Earth’s “future” can be “saved.”

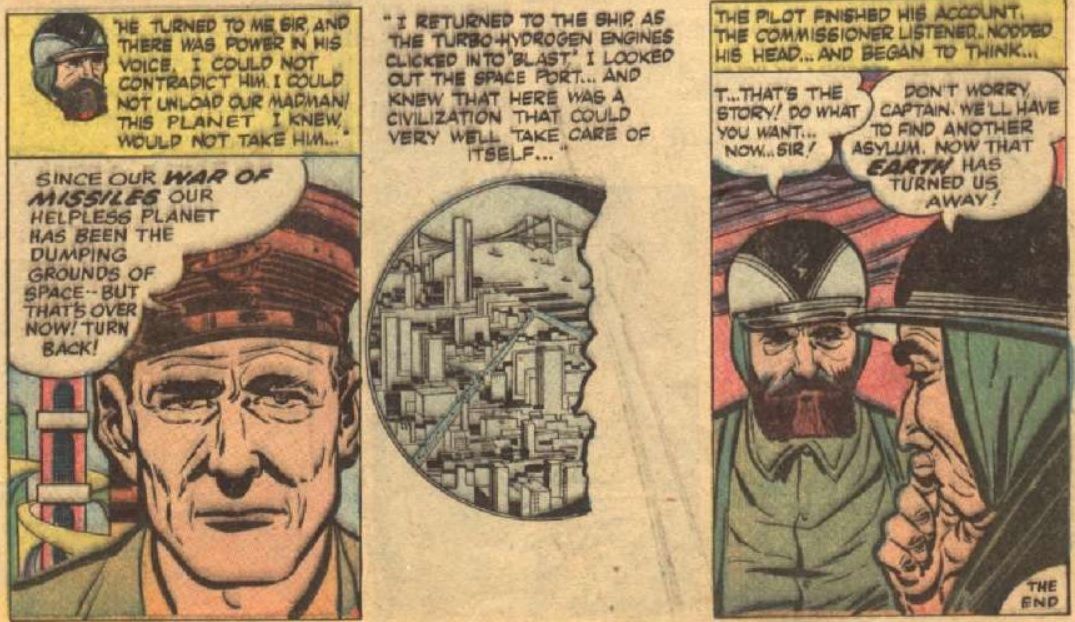

On the flip side, “Asylum,” also from Issue 1, has humanity sending its most dangerous criminals to another planet until that planet’s native population refuses to accept any more prisoners (derogatorily referred to as “madmen”). The twist reveals that this planet is Earth, which is just now reasserting itself after being nearly destroyed by their “war of missiles.” Clearly, Earth does not like being colonized, yet in the other stories, Earthlings have no compunction about running off to colonize others.

Another point of interest is the book’s claims that its stories are “based on scientific fact and theory.” Given that one story (“Disc Jockey,” Issue 1) has Martians come to Earth to silence an obnoxious DJ, Joe Rogan better hope that’s not the case.

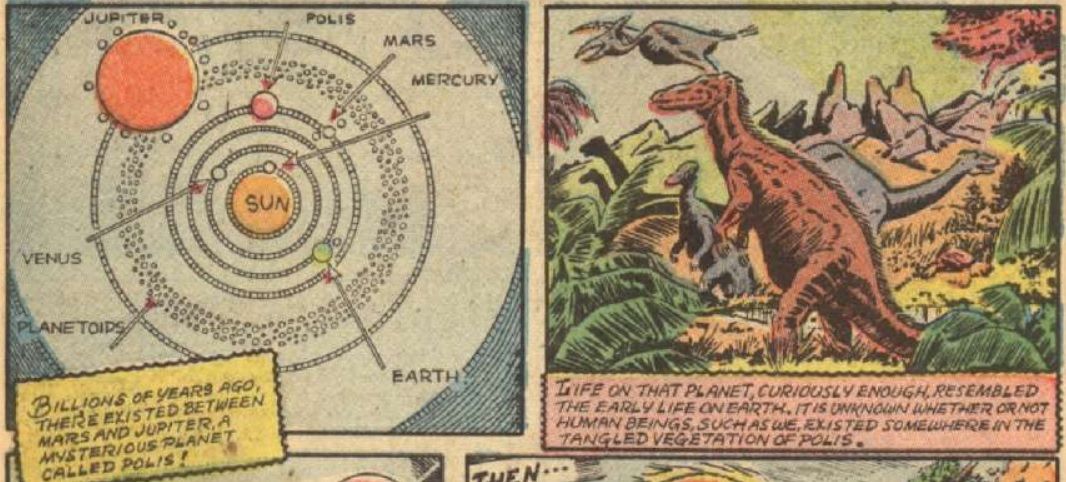

But seriously, even making allowances for how far out of date their information is, the “facts” presented here are often flat-out wrong. In “Turmoil in the Heavens!” from Issue 2, the comic tries to tell us about a Totally Real Planet named Polis that once orbited between Mars and Jupiter. It had dinosaurs and maybe even people! Then, alas, it got sucked into Jupiter’s orbit, whereupon it was broken to pieces and now survives as Jupiter and Mars’s moons.

This is, if you’ll pardon the expression, bull cookies. While there was a theory stating that a planet once existed in that orbit, that planet was called Phaeton, not Polis; the idea of Earth-like dinosaurs evolving there in such a short time is ludicrous; and the theory stated that Phaeton’s debris became the asteroid belt, not moons.

Stretching the facts like this would have been fine in a fiction story, but this is a one-page informational piece that is supposed to educate the reader.

I guess the series wasn’t doing so well, because Issue 3 tried something new: introducing recurring characters, the Three Rocketeers, in an incredibly Kirby-esque story about three guys who go on space adventures. As Issue 3 was the last, we never got to see how this idea panned out.

The Legacy

This comic was meant to capture a very specific moment and attitude, and at that, it succeeds. Some of the stories work better than others, of course, but overall, it kept my attention, and the Kirby art was a big plus.

Few stories explicitly mention the Soviet Union, the Cold War, or the Space Race, and those that do end surprisingly amicably. Nonetheless, American anxieties about all three are clear. Several of these stories emphasize the importance of sending people out to “conquer” and “colonize” space at all costs — otherwise, someone else is going to come along to conquer and colonize us. This is a very Cold War mentality: destroy or be destroyed. In that sense, the title Race FOR the Moon, which implies ownership — as opposed to Race TO the Moon, which would imply satisfaction with simply getting there — is disturbingly appropriate.

(Obviously, it never occurs to anyone that maybe colonialism in general is bad, even though the creators and characters are clearly terrified of anyone colonizing them.)

This may seem dated now, but on the other hand, the issue of who owns space and who gets to exploit its resources is still a contentious one, so who knows? Maybe we’ll see another comic like Race for the Moon someday soon, with a new generation of creators trying to persuade us that Americans are not just entitled but obligated to take what they want from whoever they want in order to survive.