The Cold War in Comics, or The Taming of the Russian

Ask an American comic book creator from the 1950s or ’60s what scared them most, and they’d probably say “communism.” Or at least, that’s the impression one gets from reading comics of the era.

The ideological and political tensions that divided the East/Soviet Union and West/USA for much of the 20th century are known simply as “the Cold War.” This is thanks to some guy who, in a fantastic bit of irony, used the term to argue for workers’ rights. (Conservatives have historically denounced unions as a communist plot, as Sharon Smith explains in Subterranean Fire: A History of Working-Class Radicalism in the United States.) While the Cold War was mostly a bloodless rivalry, it was sometimes made manifest in actual conflicts, such as the Korean War and the Vietnam War.

Given that the Cold War was such a big part of everyone’s lives for so many years, it’s inevitable that writers and artists would allow it to influence their work. Cold War comics had many ways of coping with the ever-present fear of nuclear war and ideological annihilation. I’m going to look at just a few of those ways today by examining comics from the ’50s and ’60s. While the Cold War remained a topic of conversation up until the Soviet Union’s dissolution in 1991, the tone of these discussions changed markedly in the late 1960s, as I’ve already discussed, so it made more sense (and saved a lot of time) to restrict myself to these two decades.

While most of the focus here is on comics, I do occasionally dip into TV and film to add context and highlight patterns. No medium or historical event exists in isolation. I hope that these transgressions have made for a more thorough and interesting read.

Let’s go.

Give Peace a Chance

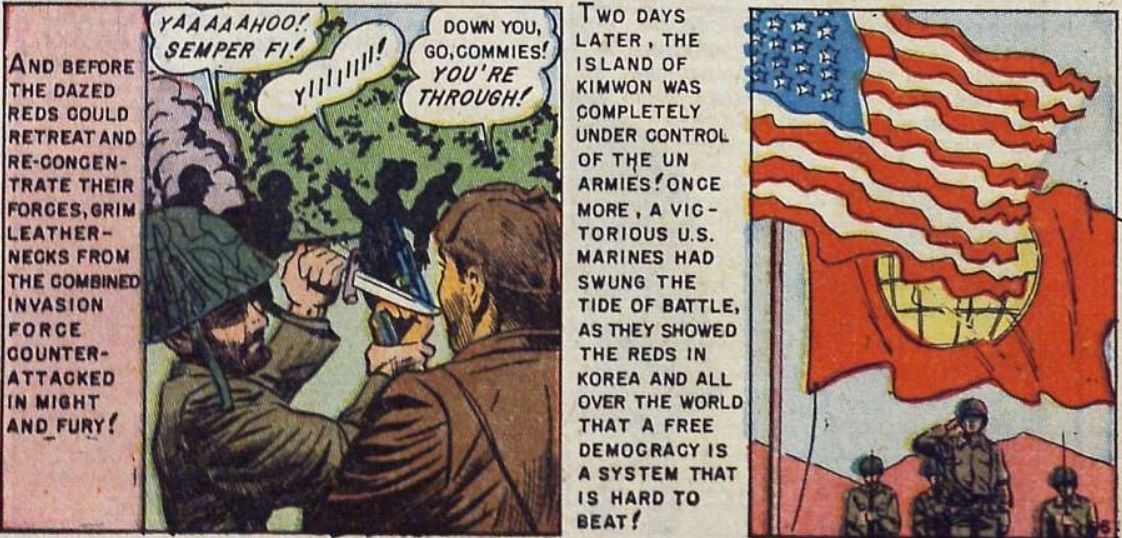

The Korean War (1950–1953) was the subject of numerous comics, but we can just use U.S. Marines in Action #1 as an example. Its four stories feature both common and uncommon themes that appeared in such comics.

In the “uncommon” category, we have overt patriotism, including images of the American flag and speechifying about how great democracy is. You’d think these elements would be everywhere, this being a war comic. Out of all the comics I read for this article, this one issue is the only place I saw them.

Most Korean War comics are straightforward battlefield adventures, which you can see in this issue when a bunch of Marines sacrifice themselves to blow up an enemy supply depot.

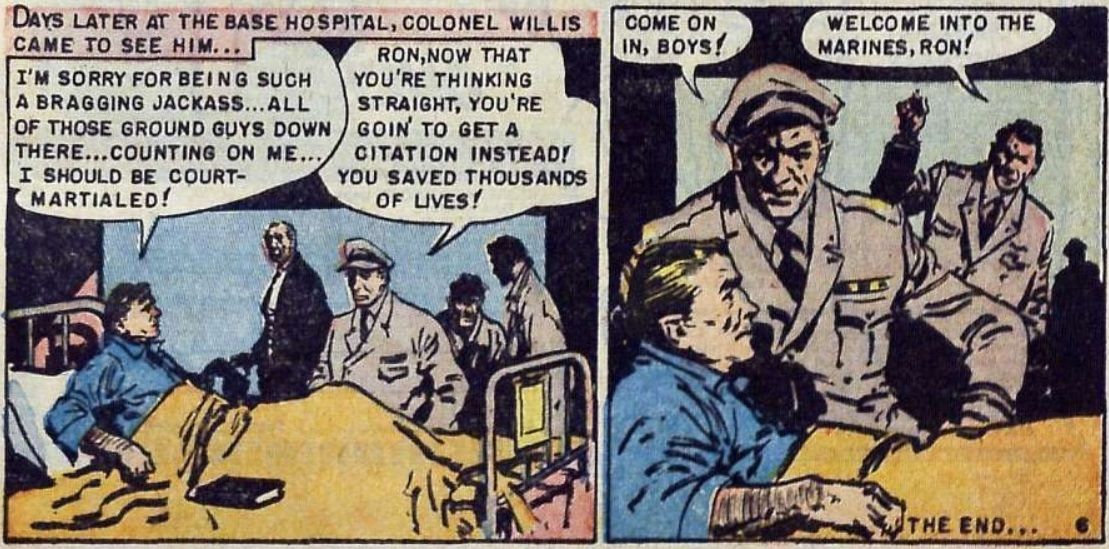

However, a good chunk of them focused on the individual human dramas of the American soldiers, with the communists as mere backdrop. These stories don’t care about the politics behind the conflict: instead, they show feuding soldiers learning to get along or belligerent loners realizing there is more to war than personal glory. (Though perhaps the fact that the enemies-to-friends plots so often involve soldiers from different classes is an anti-communist comment: hey, look, rich and poor get along fine!)

It could almost be any old war raging in the background as Commander Jerkweed here learns about the power of teamwork — a fact U.S. Marines in Action #1 acknowledged when they began another story by saying, “In our troubled, war-torn world, this could have happened at many places.”

But make no mistake: these are pro–Korean War comics. They all feature Americans charging into battle, bravely slinging racial slurs at their brutish, merciless opponents. Even the gloomiest stories end with an American soldier defeating both the communists and his inner demons, usually with a big smile.

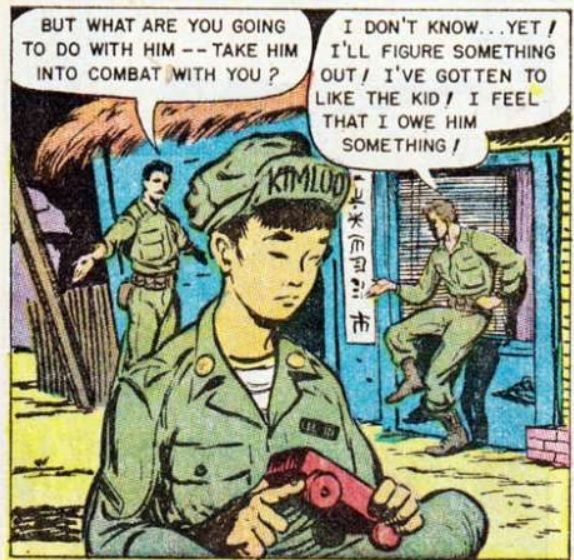

Of the titles I sampled, a grand total of one contained one line that could maybe be interpreted as an acknowledgement that Americans were doing harm in Korea. In War Heroes #4, a group of American soldiers find an orphaned Korean boy in a bombed-out village. One of the soldiers takes a shine to the kid, despite the objections of his fellows.

“I feel that I owe him something!” the softhearted soldier insists.

One doesn’t generally feel indebted to another unless they did something for you — and so far, the boy has only eaten their food and cried about his parents — or you did something to them. Perhaps the soldier feels bad that the fighting he participated in led to the boy’s current circumstances.

Anything You Can Do

Looking for more pro-America propaganda? Look no further than superhero comics.

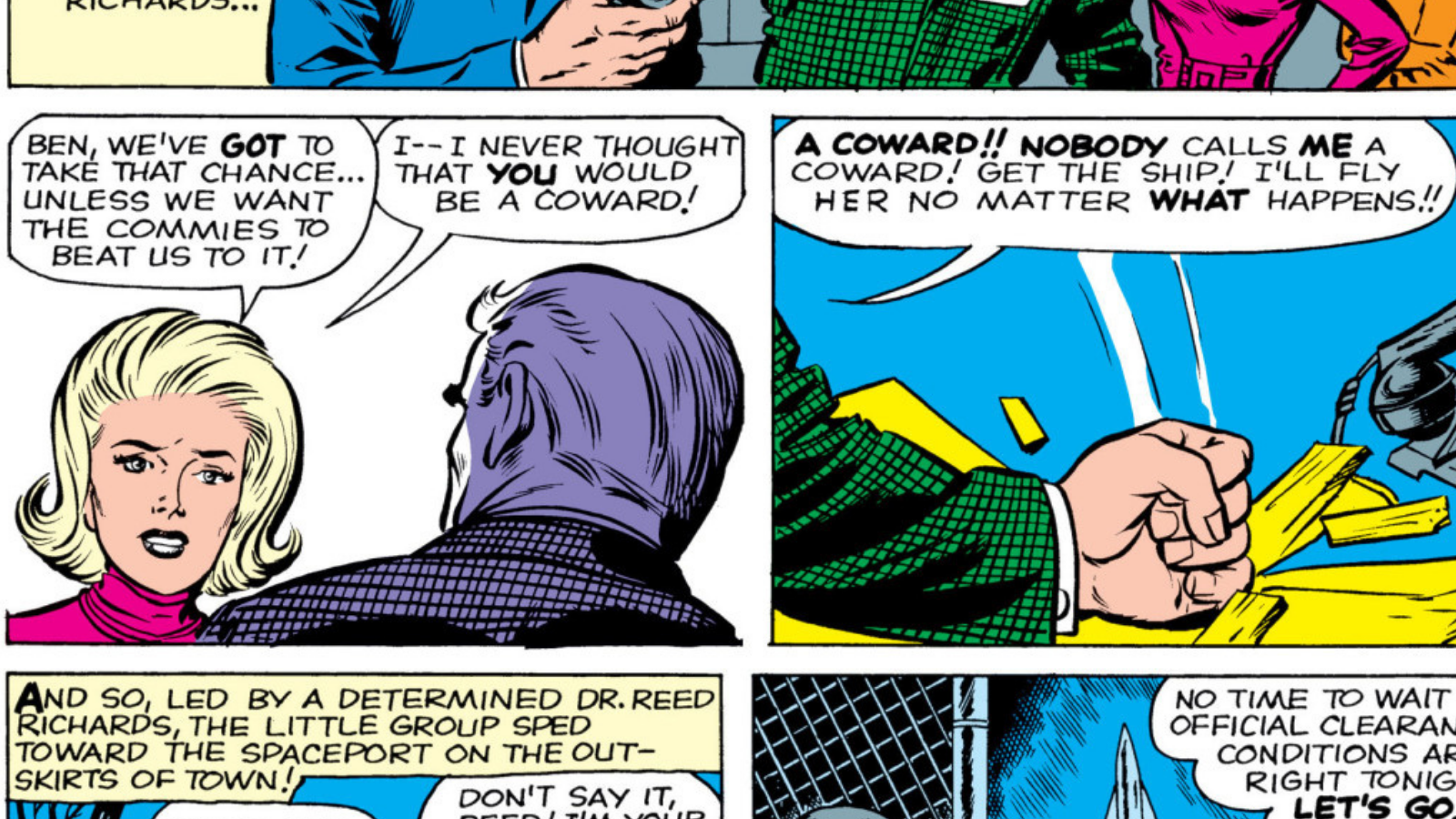

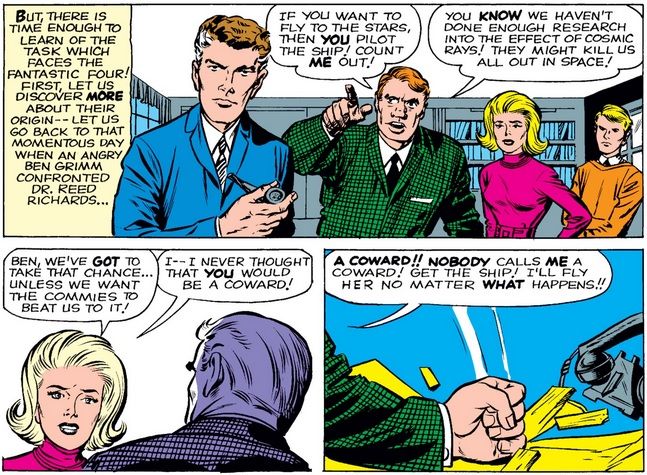

In the 1950s, Captain America was briefly resurrected as a “commie smashing” patriot. In the ’60s, Marvel’s stable of communist supervillains included (but was definitely not limited to) Titanium Man, Radioactive Man, the Unicorn, Crimson Dynamo, the Purple Man, the Red Barbarian, Abomination, Chameleon, Red Ghost…Meanwhile, Iron Man’s alter ego cranked out weapons for the Vietnam War effort, and the Fantastic Four gained their powers while trying to beat the Soviets into space.

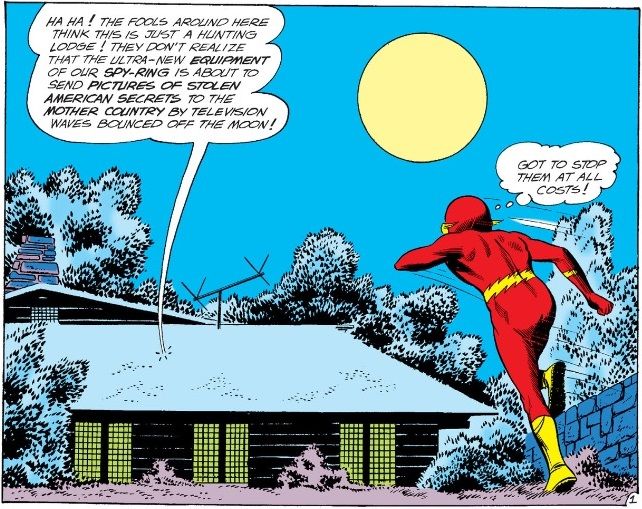

DC wasn’t as overtly anti-communist, but their heroes did have to deal with “foreign agents” from time to time. In Flash #127, Kid Flash encounters generic spies intent on stealing equally generic blueprints. While they don’t mention Russia by name, the spies do reference a “mother country.” I can only assume “mother” here was meant to invoke “Mother Russia” so that no one would think they came from, like, France.

Make ‘Em Laugh

One way to deal with something you’re scared of is to make it ridiculous. And yet, ironically, it’s a comedy film that does the kindest job of portraying Cold War tensions.

The Russians Are Coming! The Russians Are Coming! takes place in a small New England town that is suddenly “invaded” by Soviet sailors. The sailors, however, are as confused as everyone else: they damaged their submarine by accident and just want to go home. The Russian characters are treated exactly the same as the Americans: as well-meaning incompetents.

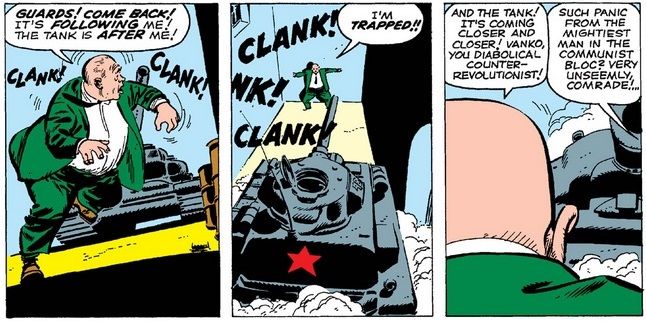

But at least these Russians were supposed to be friendly. When comics sought to put a funny spin on the Red Menace, they usually did so by mocking the enemy. Look at Tales of Suspense #46, which features a wildly unflattering caricature of General Secretary Nikita Khrushchev.

How could you possibly be afraid of a guy like this, who is so easily bullied by his own underlings? Especially with a strong, capitalist hero like Iron Man to defend you?

Khrushchev was the butt of many jokes in American media throughout the ’60s. This was in large part due to an alleged incident at the U.N.: after a delegate called out the Soviet Union for its mistreatment of Eastern Europe, Khrushchev whipped off his shoe and angrily banged it on the table. Images of excitable Russian men brandishing footwear became a punchline for years afterward, including in the last scene of Batman: The Movie.

Why Can’t We Be Friends?

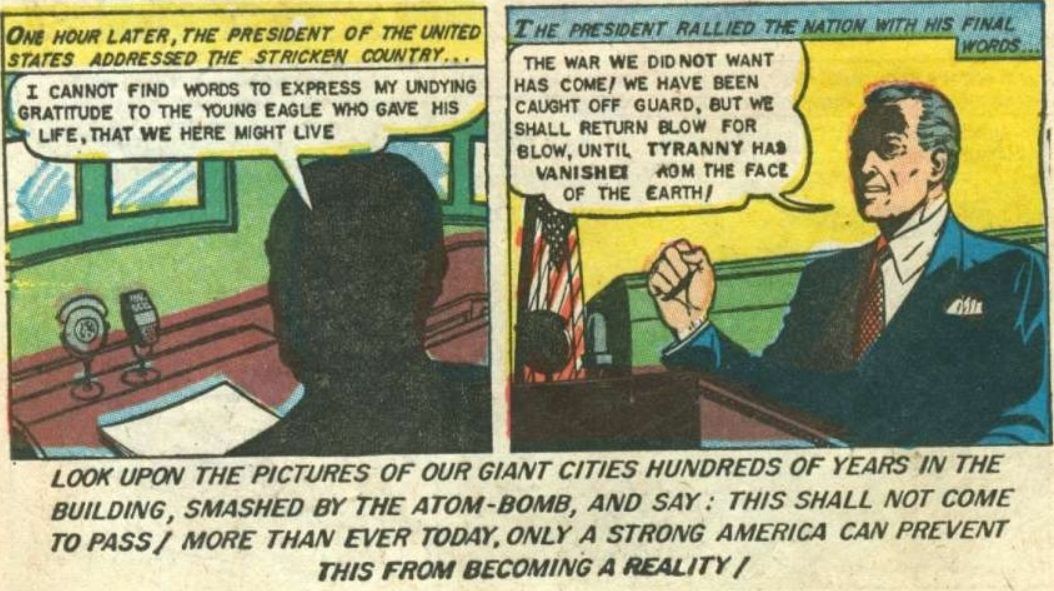

Atomic War! #1 begins on an optimistic note: the Russians have agreed to negotiate, and world peace is on the horizon. Just as those sweet, trusting Americans let their guard down, Russia swoops in and nukes several U.S. cities. The destruction is laid out across several pages, showing in horrific detail as monuments topple and doomed innocents scream in pain and terror. The message is clear: Russians cannot be trusted. A peaceful solution is not possible. Nuclear proliferation is our only hope of survival.

This was published in 1952. A decade later, thanks to less histrionic creators, we got my favorite Cold War story trope: an American and a Soviet overcome their differences and work together for the greater good, demonstrating that, beneath all the politicking, we’re all just people who want to live in peace. That’s the power of friendship, baby!

The most famous examples of this trope are not from comics, but from TV shows: The Man from U.N.C.L.E., featuring Soviet spy Illya Kuryakin, and Star Trek, featuring Ensign Chekov. Comic books don’t seem to have been too big on this story device as a rule. There’s the Black Widow, who went from enemy agent to superhero, but she had to defect to become an ally, which isn’t really in the spirit of the trope.

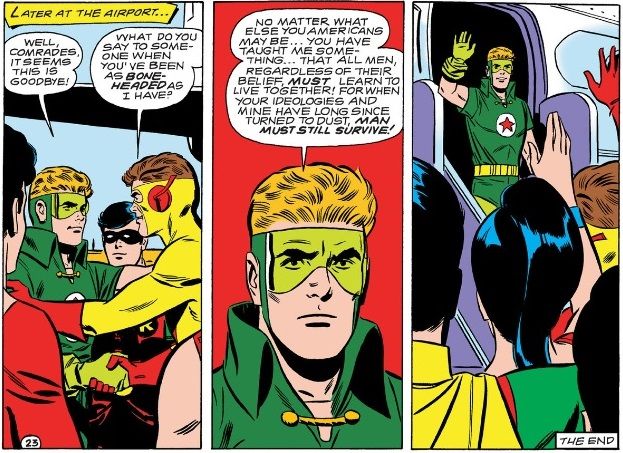

A more classic example is Starfire, a young Soviet hero who debuted in Teen Titans #18 and helped the team capture a jewel thief. Starfire doesn’t like Americans at first, but after working with the Titans, he comes to realize that we’re not so bad — or so different — after all.

And that’s my only problem with this concept: it inevitably betrays its creators’ western bias. Starfire dislikes Americans, but the Americans show no anti-Russian sentiments whatsoever. (Given that Americans created and read Atomic War!, this seems unlikely.) In order to be considered friends, the Soviets always have to do the compromising, either by admitting that America isn’t so bad or by defecting entirely, as if the Cold War was entirely their fault.

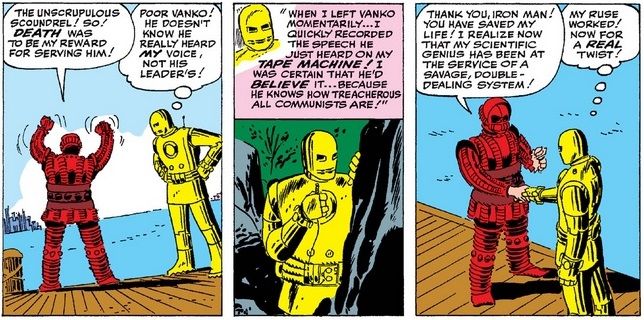

A blatant example of this comes from that classic Tales of Suspense #46, in which Iron Man lies to the Crimson Dynamo to prove how trustworthy Americans are compared to communists (don’t think about it too hard), prompting this dilly of a conversation.

Now try to imagine Iron Man — or any other hero — saying that a Soviet isn’t so bad or that we “must learn to live together” with them.

Even The Man from U.N.C.L.E. seems ashamed to admit that Illya is a Soviet and a communist. The first season is all right: he speaks with an accent, albeit a light one, and there are occasional references to his politics. (“Suddenly, I feel very Russian,” he grumbles upon arriving at a party full of rich people.) All that goes out the window pretty quick. They spend more time discussing his hair than his personal beliefs, which tells you where their priorities are.

The novels and comic books based on the series are equally reluctant to mention that whole “communist” thing — and when they do, it’s not always flattering. Quoth The Thousand Coffins Affair by Michael Avallone:

“Waverly stared glumly at Illya Nickovetch Kuryakin, marveling for the nth time at what fortune had guided U.N.C.L.E. to draw this man from behind the Iron Curtain…For all of his Russian origin, the man was an excellent U.N.C.L.E. agent.”

That’s a li’l harsh, dude.

I should also point out that, while Americans and Russian/white communists are able to cooperate so long as the Russians behave themselves, the idea that an Asian communist could be an ally never occurs to anyone. The “crime” of not being white is worse than the “crime” of being a communist.

Speaking of race…

Black and White

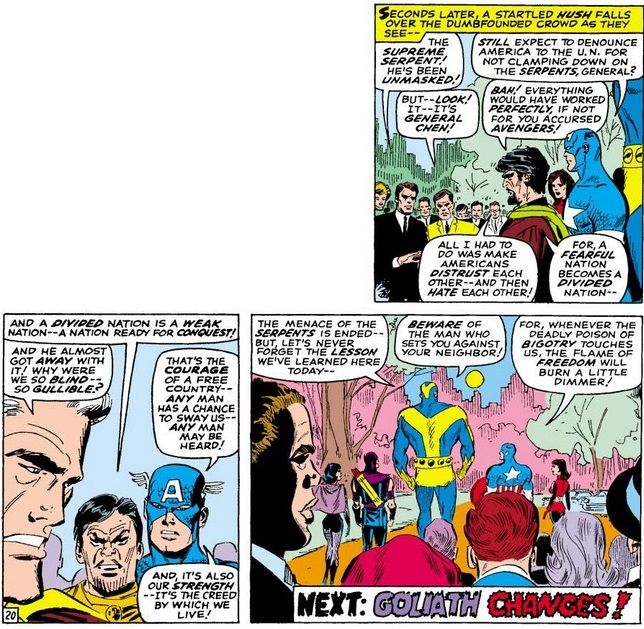

One of the rarest and most insidious ways comics used the Cold War was as a smokescreen. Take Avengers #32–33. In some ways a historic storyline, it features the Avengers confronting a racist, xenophobic hate group. They make plain that you cannot be a bigot and a real patriot, and they chastise anyone who thinks badly of others on the basis of race.

What’s this got to do with communism? In a logical world, nothing. In this one, it is revealed that the hate group’s leader is an Asian communist intent on sowing racial strife so that America would be easier to conquer.

I guess the idea that Americans could be racist without outside assistance was too far-fetched.

The troubled conversation between communism and racism was nothing new. According to Jesse Jarnow’s Wasn’t That a Time: The Weavers, the Blacklist, and the Battle for the Soul of America, in 1943, the FBI decided to investigate folk singer Pete Seeger as a potential communist. Why? Seeger dared to suggest that America shouldn’t deport all Japanese Americans after winning World War II. Cold War panic wasn’t just about economics or authoritarianism: if you believed in civil rights, then congratulations, you were a communist. Hence the plot of the 1955 film Trial.

In the film, a communist lawyer agrees to defend a Mexican boy falsely accused of murder, even as the boy’s white neighbors scream for his head. It is soon revealed that the communist does not have the boy’s best interests at heart, forcing the all-American Glenn Ford to save the day.

This revelation, just like that in Avengers #33, completely derails the discussion of racism. It distracts us with terrified hand-wringing about the Red Menace and does not engage with the communists’ assertion that everyone deserves equal rights. There’s no point: that racism stuff is a Red herring. The communists don’t really believe in equal rights, or the Americans aren’t really racist, so we don’t have to talk about it after all. What a relief!

Back in the USSR

All right, class, what have we learned about the Cold War today? That it’s bad? That the Americans are on the right side of the war? That communists are inherently shifty backstabbers? Okay, fine, but what is it? What is communism, and why do we hate it? Based on these comics, I have no idea.

Despite the diverse ways comic books and other media dealt with communism and the Cold War, vanishingly few — if any — took a serious look at the politics and ideologies that fueled it. Not everything has to be a political tract, but the fact that none of the media discussed here saw fit to specify what they were railing against is indicative of America’s mood at that moment. The dichotomy of America Good/Communism Bad — and it was always America versus communism, not capitalism versus communism — was so ingrained, so obvious, that they didn’t feel the need to tell us why.

Or maybe they were scared to explain, lest giving people actual information inspire pesky questions like “why DON’T we have equal rights?” or “what are we doing in Korea and Vietnam, really?”

So instead, they focused on people. They boiled their Cold War comics down to a few choice individuals whose depiction was easier to control than a whole war or an inscrutable ideology. This is what American media did in the ’60s: as you can read in books like Susan J. Douglas’s Where the Girls Are: Growing Up Female with the Mass Media and Gerald Nachman’s Right Here on Our Stage Tonight!: Ed Sullivan’s America, Black music artists had to look, sound, and act a certain way to sell albums to white people. (The Supremes went to charm school!) Nothing “scary” — i.e. too angry or overtly sexual — was allowed.

It’s not an exact parallel, but the motivation is the same: white America finds someone scary, so the media sanitizes them, smooths out the “rough edges,” and repackages them for suburban approval.

Nowadays, with the benefit of hindsight, we have plenty of more nuanced scholarship surrounding Cold War culture and politics. TV shows like M*A*S*H and comic books like Darwyn Cooke’s DC: The New Frontier have also revisited the era with a more critical eye. But it’s important to remember that, while the Cold War may be over, America has found other nations and ideologies to clash with. It’s worth looking back on Cold War media if only to remind ourselves how easy it is to succumb to oversimplified arguments that save us from thinking seriously about uncomfortable topics.