Queer Superhero History: Mystique

In recent years, mainstream comics publishers like DC and Marvel have made great strides in increasing the LGBTQ+ rep in their universes, though they still have a long way to go. But getting here was a slow and gradual process, with many notable landmarks — and some admitted missteps — along the way. In Queer Superhero History, we’ll look at queer characters in mainstream superhero comics, in (roughly) chronological order, to see how the landscape of LGBTQ+ rep in the genre has changed over time. Today: Mystique!

There is a famous line in the 2003 X-Men movie, X2, in which Iceman’s parents discover that their teenage son is a mutant. “Have you tried…not being a mutant?” Iceman’s mother asks him. It’s obviously meant to evoke its real-world equivalent: “Have you tried not being gay?” The mutant rights struggle in the Marvel Universe was probably most widely understood as a metaphor for civil rights and racism before X2, but this mainstream, blockbuster movie clearly — if delicately — tied it to LGBTQIA rights as well. Mutants, and the X-Men, are a metaphor for queerness (among other things).

This wouldn’t have been news to longtime X-Men readers. Chris Claremont, the writer of Uncanny X-Men from 1975 to 1991 and probably the single most important X-creator to this day, is known for many things, but among those is, uhhh…close relationships between female characters. Storm and Yukio, Kitty and Illyana (okay, Kitty and everyone)…and, of course, Mystique and Destiny.

Mystique, AKA Raven Darkholme, actually first appeared in Ms. Marvel #16 (April 1978) by Claremont and David Cockrum, though she quickly became a major X-Men villain (and occasional ally). Anyone who only knows Mystique via the movies, where she is mostly a henchwoman for Magneto with little dialogue and less agency, has been misled: Mystique henches for no one. (She also usually…wears clothes.)

Mystique’s biography is long and involved, but to hit some of the highlights: no one knows exactly how old she is, but she’s been around since at least the 1800s. She has taken a number of lovers and had a number of children. Her oldest son, Graydon Creed, was conceived with the villain Sabretooth; when Graydon turned out not to be a mutant, Mystique lost interest and abandoned him, leaving him to grow up to become an anti-mutant politician who was eventually assassinated. Her next son, Nightcrawler, was conceived with the mutant Azazel (revealed to be The Actual Devil in possibly the most hated X-Men story of all time); Mystique abandoned this child as well. The only child she actually bothered to raise was Rogue, who she adopted at age 14, but, you know, raised to be evil and inducted into the Brotherhood of Evil Mutants and stuff. It wasn’t neglect, but it wasn’t great, either. And of course, there are decades and decades of schemes, machinations, double-crosses, and flat-out murders. Suffice it to say, Raven Darkholme is not a great person.

But then there’s Destiny.

Destiny, whose real name is Irene Adler, was introduced in Uncanny X-Men #141 (January 1981), by Claremont and John Byrne (another pioneer in introducing queer characters to superhero universes). She is blind, with powerful precognitive abilities. She has also, like Mystique, been around since at least the late 1800s. In fact, they met when Irene encountered a certain “consulting detective” around the turn of the century. (For those of you who are putting two and two together: yes, this means that in the Marvel universe, Sherlock Holmes was a real person, and that real person was Mystique.)

For years, Mystique and Destiny were depicted as…close. While other members of the Brotherhood of Evil Mutants were barely tolerated colleagues at best, Mystique cared deeply for Destiny, and the two women had clearly co-parented Rogue. When Destiny was killed in 1989 (sacrificing herself for Mystique), Mystique was devastated, and her descent into unrepentant villainy after Destiny’s death is often chalked up to grief and the loss of Destiny’s stabilizing presence.

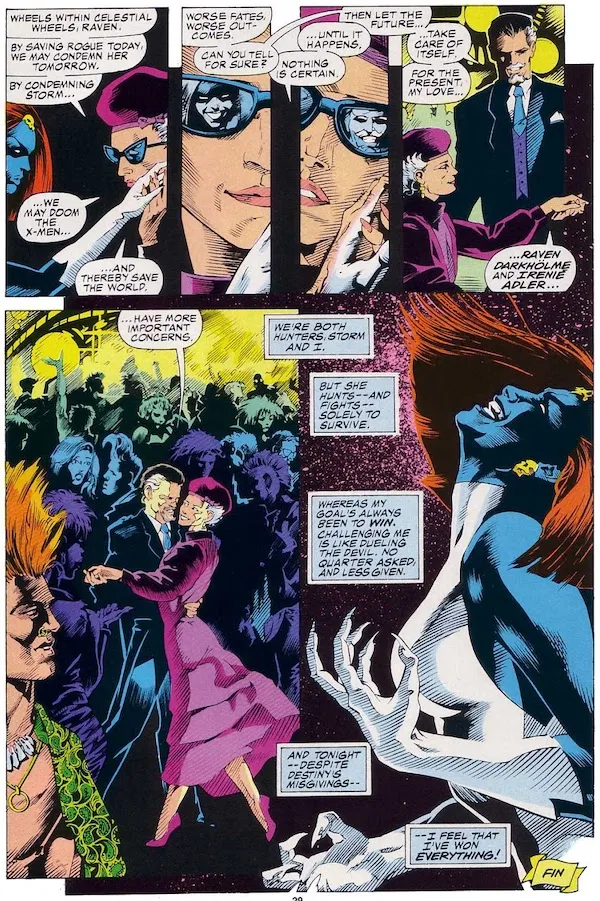

Comic book relationships tend to be intense, and as such, same-gender friendships are often read as homoerotic, usually unintentionally. At least, I don’t think we’re supposed to believe that Batman is desperately pining for Superman. But Claremont and his various collaborators crafted Mystique and Destiny’s relationship with intent. In Marvel Fanfare #40 (October 1988), Mystique and Destiny are shown dancing, with Mystique in her male “Eric Raven” form, and Mystique refers to Destiny as “my love.” In Uncanny X-Men #265 (August 1990), the villain Shadow King refers to Destiny as Mystique’s “leman,” an archaic term for a lover, particularly an illicit one.

Why the coding? Well, remember that the Comics Code forbade queer characters until 1989. More importantly, Marvel’s then editor-in-chief, Jim Shooter, allegedly had a “no gays in the Marvel Universe” policy that kept the similarly heavily coded Northstar in the closet until 1991. DC was flouting the Code by the late ’80s, but there was no such freedom at Marvel. Claremont was left with hints and implications, knowing most readers — and editors — would chalk it up to just “gals being pals.” His attempts at more overt references were shot down, like when he tried to reveal that Mystique and Destiny were Nightcrawler’s biological parents, with Mystique having taken a male form for the conception.

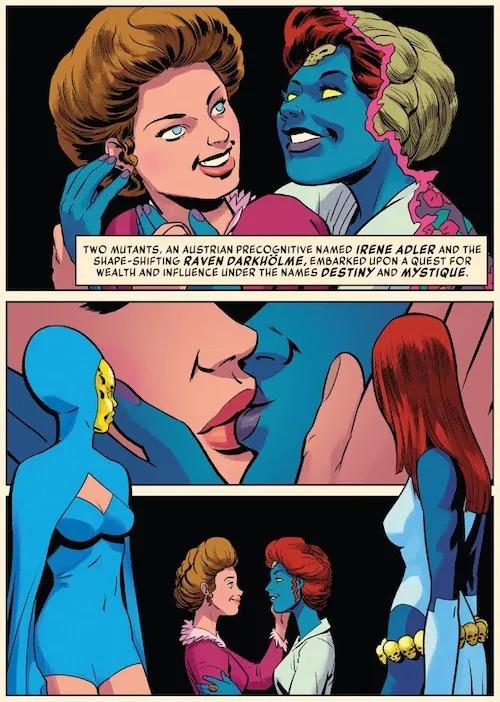

But that was then. The Code is no more, Northstar is married, and sometimes the MCU even lets unnamed characters be queer onscreen for a whole 10 seconds. (Ahem.) And Mystique and Destiny finally had the romantic subtext of their relationship become confirmed text in 2019, in History of the Marvel Universe #2, when they shared a kiss.

In retrospect, that seems…awfully late. Yes, Marvel lagged behind DC in terms of queer rep back in the ’90s, but they have plenty of queer characters now, including extremely popular ones like Hulking and Wiccan and America Chavez. Northstar got married in 2012. Iceman, of “Have you tried not being a mutant?” fame, came out in 2015. Mystique and Destiny were deliberately coded as lovers a decade before Northstar came out, so why did it take another 28 years after that to confirm what everyone already knew?

Maybe it was because it was so widely understood that Mystique and Destiny were in love that Marvel didn’t find it necessary to make it obvious. After all, a relationship can still be both queer and deeply committed without physical intimacy. Maybe Marvel wanted to maintain plausible deniability for the sake of the cinematic Mystique, who tends to be depicted as a heterosexual male fantasy first and foremost. Or maybe they just thought it didn’t matter since Destiny was dead. I don’t know.

Whatever the reason, Destiny was resurrected in 2021’s Inferno #1, and she and Mystique have been together ever since. (It was also revealed around that time that they were married before Destiny died.) At the time of this writing, Marvel seems to be hinting that November’s X-Men Blue: Origins #1 will even retcon Claremont’s original plans for Nightcrawler’s parentage into canon, with Destiny as his mother and Mystique as his biological father.

On the surface, Mystique embodies a number of negative tropes about queer characters, particularly bisexual ones: she’s heavily sexualized, she’s untrustworthy, she’s deceptive. (“Queer, arguably nonbinary shapeshifter” is a cliche all on its own, though not necessarily a negative one; we covered two of them just last month.) She’s also, frankly, a terrible person, stereotypes aside; abandoning 66% of your children does not a good samaritan make.

But she’s a great villain. And her love story with Destiny is not just compelling and moving; it is, in many ways, the most iconically queer love story in all of comics. The many decades of hiding and censorship and coded messages to readers who understood are all too real, even today. Interestingly, they stand in marked contrast to Mystique herself, who could so easily hide her mutant status, but has been out and proud about it since her debut. But it isn’t a contradiction — or if it is, it’s a contradiction that fits perfectly with the character: mutable, changeable, genderfluid; mother and monster, villain and ally, femme fatale and devoted lover. If the X-Men are a metaphor for queerness, no one embodies that more completely than Mystique, in all her complications.

So here’s to you, Mystique and Destiny, and to another 42 years together. Just…maybe don’t have any more kids, okay?