Queer Superhero History: Maggie Sawyer

In recent years, mainstream comics publishers like DC and Marvel have made great strides in increasing the LGBTQ+ rep in their universes, though they still have a long way to go. But getting here was a slow and gradual process, with many notable landmarks — and some admitted missteps — along the way. In Queer Superhero History, we’ll look at queer characters in mainstream superhero comics, in (roughly) chronological order, to see how the landscape of LGBTQ+ rep in the genre has changed over time. Today: Maggie Sawyer!

Unlike our first two trailblazers, Extraño and Cloud, Maggie Sawyer is someone fans of queer superhero media are likely to recognize, as she had a significant role in the CW’s Supergirl. Maggie bears the distinction of being the first canonical lesbian in mainstream comics…even if it took a few years for the comics to actually use that word.

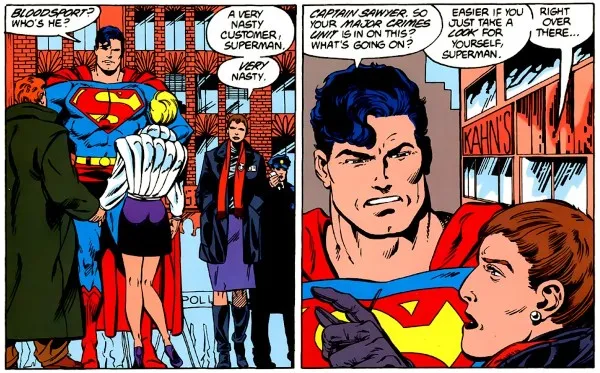

Maggie first debuted in Superman #4 (April 1987), and was created by John Byrne. She’s a captain in the Metropolis PD’s Special Crimes Unit (SCU), which deals with superpowered menaces. She becomes a recurring character in the Superman books and eventually, a grudging ally of the Man of Steel’s.

Though some fans might have had their suspicions, it’s not until Superman #15 (March 1988) that Maggie’s sexuality becomes textual, though still referred to obliquely. Maggie turns to Superman for help when her daughter, Jamie, goes missing. When Superman is surprised to hear that Maggie is married, she explains that she’s actually divorced, and that marrying her husband was a youthful mistake. “I was…confused, in those days,” she says. “There were things happening in my head that I’d been denying for a long time. Things a proper Catholic girl didn’t even want to consider.”

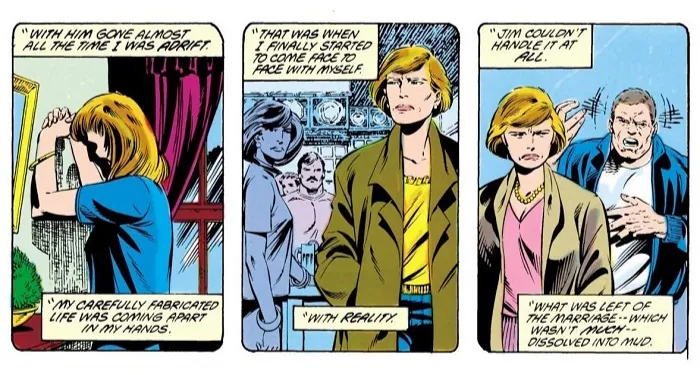

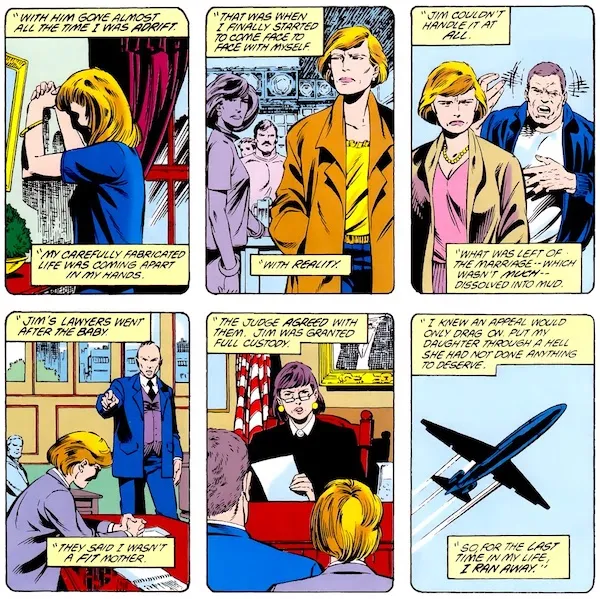

During a flashback to her marriage falling apart, one panel shows her making eye contact with another woman in a bar, while her narration box says: “I finally started to come face to face with myself. With reality.” When she and her husband finally divorced, he managed to deny her custody for not being “a fit mother.” Not wanting to put Jamie through the pain of endless legal appeals, she moved across the country to Metropolis — but now Jamie has run away and is probably somewhere in the city. (Don’t worry, Superman finds her.)

It doesn’t take much effort to read between the lines and see what Maggie’s not saying. Clark certainly picks up what she’s putting down; later, as he’s searching for Jamie, he thinks to himself that “It certainly seems ridiculous in this day and age that someone as upright as Maggie Sawyer should have to give up her child just because she’s—” before his thought is cut off by the villain of the week. (Later, he tries, albeit half-heartedly to the modern eye, to convince Jamie’s father to grant Maggie visitation.) And just in case any reader missed the hints, Maggie is also shown with a woman named Toby in her apartment, who calls her “babe” and will eventually be clearly presented as her longtime partner.

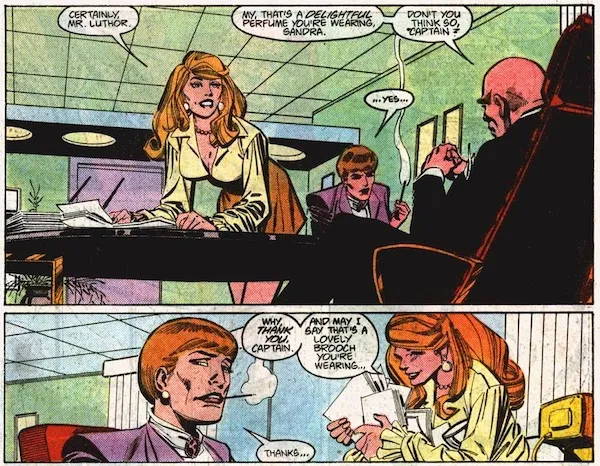

Two months later, Action Comics #600 (May 1988) kept up the heavy-handed hinting, when Lex Luthor tries to blackmail Maggie into dropping her investigation of him by alluding to her “secret.” He hammers his point home by trotting out a beautiful female assistant in a low-cut top and short skirt and commenting on his and Maggie’s “similar tastes.” Later, Maggie tells her colleague Dan Turpin (inexplicably called “Ben” here) that Lex tried to blackmail her and he says “You mean…about…” (Maggie rejects Lex’s threat, of course.)

Why the obliqueness? Well, remember, the Comics Code Authority continued to forbid queer characters until 1989. But according an article in the fan zine Amazing Heroes #144 (also discussed in the Extraño profile), that wasn’t actually the issue. John Byrne’s editor Mike Carlin is quoted as saying that Byrne could have used words like “gay” or “lesbian” but chose not to, a choice Carlin agreed with: “I don’t know how smart it would be for John to be so blatant…We do have to stay aware of who’s reading the books and whose parents might get mad if they see something like that.” This is an incredibly illuminating quote, not least because it speaks to how weak the CCA had gotten at this point; any lack of representation at DC and Marvel was clearly due to choices made by DC and Marvel, not external censorship. It’s also the second time a DC editor is quoted in that article as saying, essentially, “Think of the children!” as if queer children (and queer parents, like Maggie herself) don’t exist.

Amazing Heroes #144 also debated whether Maggie’s portrayal as relatively butch was a stereotype, with writer Mindy Newell quoted as saying “She’s cigar-chomping, she’s got short hair, she’s really tough…It might have been more effective if John had painted her as a ‘normal’ woman,” while Carlin argued “Do stereotyped dykes walk around in mini-skirts?” in Maggie’s defense. Neither argument has aged particularly well, but more to the point, they stem from Maggie being the first; as with Extraño, it’s impossible for a solitary lesbian character to be all things to all readers.

Byrne, for his part, was quoted as saying: “Whatever I say will be misinterpreted anyhow, so I’d rather let my work speak for itself. I created the first gay super-hero, [Northstar], and certainly the first gay character in Superman.” It’s a very defensive quote, and opinion may vary on the effectiveness of his execution of either character, but there’s no denying that Byrne did work hard to include queer characters in comics well before it was in vogue. (I promise we’ll get to Northstar soon!)

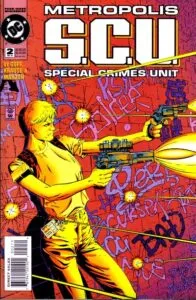

Within a few years, the landscape of comics had changed enough that Maggie could star in a miniseries, 1994’s Metropolis S.C.U. Written by Cindy Goff and drawn by Pete Krause, the series is a procedural first and foremost, but is also the first DC comic to star an out lesbian, and showcases Maggie’s struggles in her relationships with her partner Toby, her daughter, and her ex due to her workaholism. This nuanced, three-dimensional portrayal of a gay lead earned the book a 1996 GLAAD Media Award for Outstanding Comic.

In the 2000s, Maggie moved to Gotham and joined the cast of a different procedural, Gotham Central. During the New 52 reboot in 2011, she began a relationship with Batwoman, Kate Kane. However, when Kate proposed in 2013, DC infamously forbade the marriage, causing Batwoman’s creative team, J.H. Williams III and W. Haden Blackman, to leave the book. DC insisted that their refusal was not because Kate and Maggie were gay, but because superheroes weren’t allowed to have happy personal lives. To be fair, DC had torpedoed many iconic heterosexual marriages at the time, all the way up to Superman’s. But the optics of forbidding a lesbian wedding in particular — what would have been the first lesbian wedding in comics, and only the third same-sex wedding in superhero comics history (with #2 occurring only the year before, in 2012) — were extremely bad.

As of the 2016 Rebirth reboot, Maggie is back in Metropolis and the Superman books.

But Maggie’s life isn’t just limited to comics. She was a recurring character on Superman: The Animated Series, where she was voiced by Joanna Cassidy and which premiered in 1996, making her one of the very first LGBTQ characters in children’s animation — although they were back to referencing her sexuality obliquely by showing Toby visiting her in the hospital rather than stating it explicitly. She also appeared in live action in Smallville, played by Jill Teed.

However, she’s best known for her appearances in seasons 2 and 3 of Supergirl, where she was played by Floriana Lima (and also portrayed as Latina for the first time, although Lima herself is not Latina). Unlike prior tentative television appearances, Supergirl put Maggie’s sexuality front and center via her relationship with Supergirl’s sister Alex Danvers. Over the course of two seasons, Alex comes to terms with her own sexuality, Maggie confronts her father about his homophobia, and Alex and Maggie get engaged, only to sadly break it off when they realize that they disagree about whether or not they want kids (Alex does, Maggie doesn’t — slightly ironically considering that she was the first queer parent in comics). Maggie was not the first queer character in a DC live action property, but the prominence of her storyline makes it a significant moment in DC’s queer history regardless. (It does, however, make her two for two on storylines where her engagement to another woman falls through.)

Our first two profiles covered extremely obscure characters, but Maggie has been a regular part of Superman’s milieu for 35 years, and there’s no reason not to expect that to continue. She’s also been consistently portrayed as brave, upstanding, stubborn as all get-out, and unafraid to be exactly who she is. Superhero comics have a long and troubling history with copaganda that they are only now beginning (just barely) to engage with, and as with her fellow lesbian cop/Batwoman ex Renee Montoya, it’s not entirely clear yet what that will mean for Maggie’s role in the larger Superman narrative. But hopefully DC can move away from their history of unthinking copaganda while still letting us keep the compelling, important character Maggie has been for over three decades now.

And hopefully the next time she gets proposed to, she can actually make it to the damn altar.