Madeline Miller’s Books Deepened My Appreciation for Greek Mythology

This content contains affiliate links. When you buy through these links, we may earn an affiliate commission.

Trigger Warning: Mention of sexual assault

In high school and college, Greek epics like Homer’s Iliad and Odyssey were never among my favorites. This is partly my personal preference and partly a generational difference. My Baby Boomer mom read—and translated passages from—The Odyssey, The Iliad, and The Aeneid in their original Greek and Latin in high school. This was common in her generation but rare in mine—virtually unheard of among friends my age. So, I’m exactly the target audience for Madeline Miller’s retellings of Greek epics: a Millennial feminist sexual assault survivor who’d only read these classics in English translations.

I’ve always found the stories and themes of Greek mythology fascinating but struggled to get into the style. Maybe it was the mnemonic devices and epithets that the poets used to remember incredibly long oral poems. Maybe it was the translations, the countless iterations of these stories, or the stilted style. Whatever the reason, characters in Greek myths and plays always seemed more like cartoons or archetypes than real people to me.

Perhaps the ancient Greeks felt this narrative distance from their heroes, or maybe Homer seemed as fresh to them as our favorite current movies, shows, and novels. Either way, Miller restores the characters’ vividness and humanity. Even minor immortals like Circe have achingly human emotions. No longer just larger-than-life heroes like “wily Odysseus,” Odysseus and Achilles are compelling, passionate, arrogant men. Miller has degrees in Classics and taught Greek and Latin. She’s translated the language, interpreted the stories, and then reimagined them with lots of artistic liberties. They’re not a replacement for Homer’s work, but they complement them beautifully.

A powerful scene in Miller’s retelling of The Iliad, The Song of Achilles, reimagines the sacrifice of Iphigenia. In most versions, including Aeschylus’s Oresteia trilogy, which I read in high school, Agamemnon sacrifices his daughter, Iphigenia, so the goddess Artemis will send wind to move his ship. Miller’s novel adds another layer of deceit: Iphigenia is tricked into thinking that she is attending her own wedding to Achilles, whom she considers attractive. In both versions, this is a horrifying story of a parent murdering a child. However, in Miller’s novel, Iphigenia’s naïve hope makes her a relatable character, not just a victim and plot device.

Perhaps the ancient Greeks felt this narrative distance from their heroes, or maybe Homer seemed as fresh to them as our favorite current movies, shows, and novels. Either way, Miller restores the characters’ vividness and humanity. Even minor immortals like Circe have achingly human emotions. No longer just larger-than-life heroes like “wily Odysseus,” Odysseus and Achilles are compelling, passionate, arrogant men. Miller has degrees in Classics and taught Greek and Latin. She’s translated the language, interpreted the stories, and then reimagined them with lots of artistic liberties. They’re not a replacement for Homer’s work, but they complement them beautifully.

A powerful scene in Miller’s retelling of The Iliad, The Song of Achilles, reimagines the sacrifice of Iphigenia. In most versions, including Aeschylus’s Oresteia trilogy, which I read in high school, Agamemnon sacrifices his daughter, Iphigenia, so the goddess Artemis will send wind to move his ship. Miller’s novel adds another layer of deceit: Iphigenia is tricked into thinking that she is attending her own wedding to Achilles, whom she considers attractive. In both versions, this is a horrifying story of a parent murdering a child. However, in Miller’s novel, Iphigenia’s naïve hope makes her a relatable character, not just a victim and plot device.

Miller’s interpretation of Briseis, captured and given to Achilles as a war prize, also gives a female character more agency than in the original. In the 2004 movie Troy, Briseis (Rose Byrne) has sudden, passionate sex with Achilles (Brad Pitt). This movie from my high school years further muddled the details of The Iliad in my memory. While a sex scene between them made sense in a 2004 blockbuster, in Miller’s novel, we understand Briseis’s gradual, close, non-sexual friendships with Patroclus and Achilles after they prevent Agamemnon from raping her.

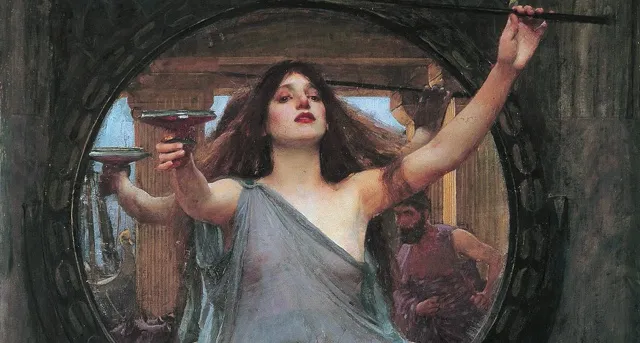

Miller’s greatest feminist reimagining is Circe herself. She’s best known as a sorceress in The Odyssey, who literally turns Odysseus and his men into pigs. In any version of the story, there’s a potential sexual metaphor. Over time, readers’ perspective on who is the sexual predator in this story has shifted. From the Middle Ages to the Victorian era, Circe symbolized a dangerous, sexually predatory woman. From a patriarchal or victim-blaming perspective, turning men into pigs can suggest that victims tempt rapists, who cannot control themselves sexually. Miller’s Circe inverts this symbolism. She turns the men into pigs as revenge after they rape her. “Men make terrible pigs,” she says (194). Whether or not readers agree with Circe’s methods, it’s unambiguous that rapists are completely responsible for their actions. They choose to be rapists, then are turned into pigs unwillingly, rather than losing self-control through animalistic lust.

Miller informs her modern interpretation of ancient mythology with contemporary scientific findings. Some geneticists think that humans never had blue eyes until around 7,000 years ago. In The Song of Achilles, the ancient Greeks love golden or blond hair but find blue eyes monstrous. Achilles and Agamemnon think that the priest Calchas has “freakish blue eyes” (264). Because I’m disabled, I’ve always been curious about what people consider beautiful, normal, or abnormal, and how unfamiliarity, ableism, and racism can influence these standards. These ideas are so arbitrary that mutations considered “freakish” in one era or society can easily be idealized or fetishized in another. Other characters’ reactions to Calchas’s eyes show how arbitrary these norms really are. Miller’s 21st century feminist perspective inverts many of the assumptions in earlier interpretations of Greek myths.

Miller’s interpretation of Briseis, captured and given to Achilles as a war prize, also gives a female character more agency than in the original. In the 2004 movie Troy, Briseis (Rose Byrne) has sudden, passionate sex with Achilles (Brad Pitt). This movie from my high school years further muddled the details of The Iliad in my memory. While a sex scene between them made sense in a 2004 blockbuster, in Miller’s novel, we understand Briseis’s gradual, close, non-sexual friendships with Patroclus and Achilles after they prevent Agamemnon from raping her.

Miller’s greatest feminist reimagining is Circe herself. She’s best known as a sorceress in The Odyssey, who literally turns Odysseus and his men into pigs. In any version of the story, there’s a potential sexual metaphor. Over time, readers’ perspective on who is the sexual predator in this story has shifted. From the Middle Ages to the Victorian era, Circe symbolized a dangerous, sexually predatory woman. From a patriarchal or victim-blaming perspective, turning men into pigs can suggest that victims tempt rapists, who cannot control themselves sexually. Miller’s Circe inverts this symbolism. She turns the men into pigs as revenge after they rape her. “Men make terrible pigs,” she says (194). Whether or not readers agree with Circe’s methods, it’s unambiguous that rapists are completely responsible for their actions. They choose to be rapists, then are turned into pigs unwillingly, rather than losing self-control through animalistic lust.

Miller informs her modern interpretation of ancient mythology with contemporary scientific findings. Some geneticists think that humans never had blue eyes until around 7,000 years ago. In The Song of Achilles, the ancient Greeks love golden or blond hair but find blue eyes monstrous. Achilles and Agamemnon think that the priest Calchas has “freakish blue eyes” (264). Because I’m disabled, I’ve always been curious about what people consider beautiful, normal, or abnormal, and how unfamiliarity, ableism, and racism can influence these standards. These ideas are so arbitrary that mutations considered “freakish” in one era or society can easily be idealized or fetishized in another. Other characters’ reactions to Calchas’s eyes show how arbitrary these norms really are. Miller’s 21st century feminist perspective inverts many of the assumptions in earlier interpretations of Greek myths.

Perhaps the ancient Greeks felt this narrative distance from their heroes, or maybe Homer seemed as fresh to them as our favorite current movies, shows, and novels. Either way, Miller restores the characters’ vividness and humanity. Even minor immortals like Circe have achingly human emotions. No longer just larger-than-life heroes like “wily Odysseus,” Odysseus and Achilles are compelling, passionate, arrogant men. Miller has degrees in Classics and taught Greek and Latin. She’s translated the language, interpreted the stories, and then reimagined them with lots of artistic liberties. They’re not a replacement for Homer’s work, but they complement them beautifully.

A powerful scene in Miller’s retelling of The Iliad, The Song of Achilles, reimagines the sacrifice of Iphigenia. In most versions, including Aeschylus’s Oresteia trilogy, which I read in high school, Agamemnon sacrifices his daughter, Iphigenia, so the goddess Artemis will send wind to move his ship. Miller’s novel adds another layer of deceit: Iphigenia is tricked into thinking that she is attending her own wedding to Achilles, whom she considers attractive. In both versions, this is a horrifying story of a parent murdering a child. However, in Miller’s novel, Iphigenia’s naïve hope makes her a relatable character, not just a victim and plot device.

Perhaps the ancient Greeks felt this narrative distance from their heroes, or maybe Homer seemed as fresh to them as our favorite current movies, shows, and novels. Either way, Miller restores the characters’ vividness and humanity. Even minor immortals like Circe have achingly human emotions. No longer just larger-than-life heroes like “wily Odysseus,” Odysseus and Achilles are compelling, passionate, arrogant men. Miller has degrees in Classics and taught Greek and Latin. She’s translated the language, interpreted the stories, and then reimagined them with lots of artistic liberties. They’re not a replacement for Homer’s work, but they complement them beautifully.

A powerful scene in Miller’s retelling of The Iliad, The Song of Achilles, reimagines the sacrifice of Iphigenia. In most versions, including Aeschylus’s Oresteia trilogy, which I read in high school, Agamemnon sacrifices his daughter, Iphigenia, so the goddess Artemis will send wind to move his ship. Miller’s novel adds another layer of deceit: Iphigenia is tricked into thinking that she is attending her own wedding to Achilles, whom she considers attractive. In both versions, this is a horrifying story of a parent murdering a child. However, in Miller’s novel, Iphigenia’s naïve hope makes her a relatable character, not just a victim and plot device.

Miller’s interpretation of Briseis, captured and given to Achilles as a war prize, also gives a female character more agency than in the original. In the 2004 movie Troy, Briseis (Rose Byrne) has sudden, passionate sex with Achilles (Brad Pitt). This movie from my high school years further muddled the details of The Iliad in my memory. While a sex scene between them made sense in a 2004 blockbuster, in Miller’s novel, we understand Briseis’s gradual, close, non-sexual friendships with Patroclus and Achilles after they prevent Agamemnon from raping her.

Miller’s greatest feminist reimagining is Circe herself. She’s best known as a sorceress in The Odyssey, who literally turns Odysseus and his men into pigs. In any version of the story, there’s a potential sexual metaphor. Over time, readers’ perspective on who is the sexual predator in this story has shifted. From the Middle Ages to the Victorian era, Circe symbolized a dangerous, sexually predatory woman. From a patriarchal or victim-blaming perspective, turning men into pigs can suggest that victims tempt rapists, who cannot control themselves sexually. Miller’s Circe inverts this symbolism. She turns the men into pigs as revenge after they rape her. “Men make terrible pigs,” she says (194). Whether or not readers agree with Circe’s methods, it’s unambiguous that rapists are completely responsible for their actions. They choose to be rapists, then are turned into pigs unwillingly, rather than losing self-control through animalistic lust.

Miller informs her modern interpretation of ancient mythology with contemporary scientific findings. Some geneticists think that humans never had blue eyes until around 7,000 years ago. In The Song of Achilles, the ancient Greeks love golden or blond hair but find blue eyes monstrous. Achilles and Agamemnon think that the priest Calchas has “freakish blue eyes” (264). Because I’m disabled, I’ve always been curious about what people consider beautiful, normal, or abnormal, and how unfamiliarity, ableism, and racism can influence these standards. These ideas are so arbitrary that mutations considered “freakish” in one era or society can easily be idealized or fetishized in another. Other characters’ reactions to Calchas’s eyes show how arbitrary these norms really are. Miller’s 21st century feminist perspective inverts many of the assumptions in earlier interpretations of Greek myths.

Miller’s interpretation of Briseis, captured and given to Achilles as a war prize, also gives a female character more agency than in the original. In the 2004 movie Troy, Briseis (Rose Byrne) has sudden, passionate sex with Achilles (Brad Pitt). This movie from my high school years further muddled the details of The Iliad in my memory. While a sex scene between them made sense in a 2004 blockbuster, in Miller’s novel, we understand Briseis’s gradual, close, non-sexual friendships with Patroclus and Achilles after they prevent Agamemnon from raping her.

Miller’s greatest feminist reimagining is Circe herself. She’s best known as a sorceress in The Odyssey, who literally turns Odysseus and his men into pigs. In any version of the story, there’s a potential sexual metaphor. Over time, readers’ perspective on who is the sexual predator in this story has shifted. From the Middle Ages to the Victorian era, Circe symbolized a dangerous, sexually predatory woman. From a patriarchal or victim-blaming perspective, turning men into pigs can suggest that victims tempt rapists, who cannot control themselves sexually. Miller’s Circe inverts this symbolism. She turns the men into pigs as revenge after they rape her. “Men make terrible pigs,” she says (194). Whether or not readers agree with Circe’s methods, it’s unambiguous that rapists are completely responsible for their actions. They choose to be rapists, then are turned into pigs unwillingly, rather than losing self-control through animalistic lust.

Miller informs her modern interpretation of ancient mythology with contemporary scientific findings. Some geneticists think that humans never had blue eyes until around 7,000 years ago. In The Song of Achilles, the ancient Greeks love golden or blond hair but find blue eyes monstrous. Achilles and Agamemnon think that the priest Calchas has “freakish blue eyes” (264). Because I’m disabled, I’ve always been curious about what people consider beautiful, normal, or abnormal, and how unfamiliarity, ableism, and racism can influence these standards. These ideas are so arbitrary that mutations considered “freakish” in one era or society can easily be idealized or fetishized in another. Other characters’ reactions to Calchas’s eyes show how arbitrary these norms really are. Miller’s 21st century feminist perspective inverts many of the assumptions in earlier interpretations of Greek myths.