Let’s Talk About Ursula K. Le Guin, Oscar Wilde, and Taoism

This content contains affiliate links. When you buy through these links, we may earn an affiliate commission.

Ursula K. Le Guin’s recent passing still feels a little unreal to me, for a bucketful of reasons. But especially because it’s come at a weird, downright uncanny juncture in my life.

I’ve been lately reading a little bit about Taoism, and had stumbled across a translation of the fundamental Taoism text, the Tao Te Ching…and who was behind this rendition but none other than Le Guin herself!

So naturally I wondered, how on earth did the landmark science fiction writer Ursula K. Le Guin end up involved translating one of the most famous Chinese texts in history?

I’ve been lately reading a little bit about Taoism, and had stumbled across a translation of the fundamental Taoism text, the Tao Te Ching…and who was behind this rendition but none other than Le Guin herself!

So naturally I wondered, how on earth did the landmark science fiction writer Ursula K. Le Guin end up involved translating one of the most famous Chinese texts in history?

Lao Tzu’s ancient and timeless philosophy of simplicity and naturalness must’ve really connected with Le Guin, because her books are practically bursting with Taoist thought. She flat out called her book The Lathe of Heaven a Taoist novel; its name comes from a translation of the Chuang Tzu, a fundamental Taoist text by another famous Taoist called Chuang Tzu, and this lovely quote:

“To let understanding stop at what cannot be understood is a high attainment. Those who cannot do it will be destroyed on the lathe of heaven.”

Lao Tzu’s ancient and timeless philosophy of simplicity and naturalness must’ve really connected with Le Guin, because her books are practically bursting with Taoist thought. She flat out called her book The Lathe of Heaven a Taoist novel; its name comes from a translation of the Chuang Tzu, a fundamental Taoist text by another famous Taoist called Chuang Tzu, and this lovely quote:

“To let understanding stop at what cannot be understood is a high attainment. Those who cannot do it will be destroyed on the lathe of heaven.”

The Tao Te Ching is one of the most translated works in the world, practically daring people to roll up their sleeves and—c’mon!—try their luck at the sucker. And since her twenties, Le Guin had been slowly but surely translating the Tao Te Ching herself for modern readers, while keeping Lao Tzu’s poetry.

Now, there was a tiny problem, namely: she didn’t know Chinese…but she certainly didn’t let that get in her way. She instead utilized existing translations, and collaborated with experts to create a new rendition of the legendary text. And, personally, it’s one of the most approachable, enjoyable, and satisfying. Here’s a snippet where I think Le Guin beautifully highlights Lao Tzu’s thoughtfulness (and sense of humor):

Thirty spokes

meet in the hub.

Where the wheel isn’t

is where it’s useful.

Hollowed out,

clay makes a pot.

Where the pot’s not

is where it’s useful.

Cut doors and windows

to make a room.

Where the room isn’t,

there’s room for you.

So the profit in what is

is in the use of what isn’t.

The Tao Te Ching is one of the most translated works in the world, practically daring people to roll up their sleeves and—c’mon!—try their luck at the sucker. And since her twenties, Le Guin had been slowly but surely translating the Tao Te Ching herself for modern readers, while keeping Lao Tzu’s poetry.

Now, there was a tiny problem, namely: she didn’t know Chinese…but she certainly didn’t let that get in her way. She instead utilized existing translations, and collaborated with experts to create a new rendition of the legendary text. And, personally, it’s one of the most approachable, enjoyable, and satisfying. Here’s a snippet where I think Le Guin beautifully highlights Lao Tzu’s thoughtfulness (and sense of humor):

Thirty spokes

meet in the hub.

Where the wheel isn’t

is where it’s useful.

Hollowed out,

clay makes a pot.

Where the pot’s not

is where it’s useful.

Cut doors and windows

to make a room.

Where the room isn’t,

there’s room for you.

So the profit in what is

is in the use of what isn’t.

As I delved into Le Guin’s background with Taoism, I discovered that she’s far from the only hero of mine to be enamored by the philosophy. Perhaps most surprising to find is one of my favorite writers, Oscar Wilde. He even wrote a review of an English translation of the Chuang Tzu (the title and author’s name, as Wilde says, “must carefully be pronounced as it is not written”).

And, in short, Wilde was clearly absolutely charmed and intrigued by what he read. Like teenage Le Guin finding a common anarchist in Lao Tzu, Wilde saw an exciting rabble rouser in the ancient writer Chuang Tzu: “He would be disturbing at dinner-parties, and impossible at afternoon teas.”

It’s hard to say how much Chuang Tzu directly influenced Wilde’s life, if at all. But it’s easy to see how Lao Tzu, Chuang Tzu, Le Guin, and Oscar Wilde all shared some similar thoughts, and would probably get on fabulously. In fact, as blogger Heidi C. Parton has pointed out, some of Oscar Wilde’s famous witty quips would be eerily familiar to a Taoist:

Chuang Tzu wrote, “What starts out being sincere usually ends up being deceitful.”

…Or, as Oscar Wilde put it, “A little sincerity is a dangerous thing, and a great deal of it is absolutely fatal.”

As I delved into Le Guin’s background with Taoism, I discovered that she’s far from the only hero of mine to be enamored by the philosophy. Perhaps most surprising to find is one of my favorite writers, Oscar Wilde. He even wrote a review of an English translation of the Chuang Tzu (the title and author’s name, as Wilde says, “must carefully be pronounced as it is not written”).

And, in short, Wilde was clearly absolutely charmed and intrigued by what he read. Like teenage Le Guin finding a common anarchist in Lao Tzu, Wilde saw an exciting rabble rouser in the ancient writer Chuang Tzu: “He would be disturbing at dinner-parties, and impossible at afternoon teas.”

It’s hard to say how much Chuang Tzu directly influenced Wilde’s life, if at all. But it’s easy to see how Lao Tzu, Chuang Tzu, Le Guin, and Oscar Wilde all shared some similar thoughts, and would probably get on fabulously. In fact, as blogger Heidi C. Parton has pointed out, some of Oscar Wilde’s famous witty quips would be eerily familiar to a Taoist:

Chuang Tzu wrote, “What starts out being sincere usually ends up being deceitful.”

…Or, as Oscar Wilde put it, “A little sincerity is a dangerous thing, and a great deal of it is absolutely fatal.”

I’ve been lately reading a little bit about Taoism, and had stumbled across a translation of the fundamental Taoism text, the Tao Te Ching…and who was behind this rendition but none other than Le Guin herself!

So naturally I wondered, how on earth did the landmark science fiction writer Ursula K. Le Guin end up involved translating one of the most famous Chinese texts in history?

I’ve been lately reading a little bit about Taoism, and had stumbled across a translation of the fundamental Taoism text, the Tao Te Ching…and who was behind this rendition but none other than Le Guin herself!

So naturally I wondered, how on earth did the landmark science fiction writer Ursula K. Le Guin end up involved translating one of the most famous Chinese texts in history?

When Ursula Met Lao Tzu…

Le Guin was an unabashed anarchist. Her writing often carries an anarchic wit, whether it was poking at utopias, power dynamics, gender roles, and so on. So it should be no surprise that as a teenager, her anarchic soul found a kindred soul in Taoism founder Lao Tzu and his text, the Tao Te Ching. The book, sitting on her family’s living room shelves, captured her curiosity. She later wryly said about her dad’s copy, “The translation’s very bad actually, but the book is wonderful, and I just fell for it.” Lao Tzu’s ancient and timeless philosophy of simplicity and naturalness must’ve really connected with Le Guin, because her books are practically bursting with Taoist thought. She flat out called her book The Lathe of Heaven a Taoist novel; its name comes from a translation of the Chuang Tzu, a fundamental Taoist text by another famous Taoist called Chuang Tzu, and this lovely quote:

“To let understanding stop at what cannot be understood is a high attainment. Those who cannot do it will be destroyed on the lathe of heaven.”

Lao Tzu’s ancient and timeless philosophy of simplicity and naturalness must’ve really connected with Le Guin, because her books are practically bursting with Taoist thought. She flat out called her book The Lathe of Heaven a Taoist novel; its name comes from a translation of the Chuang Tzu, a fundamental Taoist text by another famous Taoist called Chuang Tzu, and this lovely quote:

“To let understanding stop at what cannot be understood is a high attainment. Those who cannot do it will be destroyed on the lathe of heaven.”

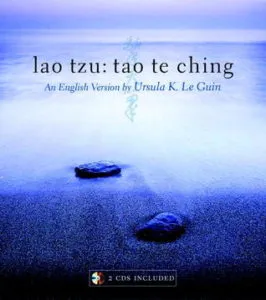

Translating the tao te ching

The Tao Te Ching is one of the most translated works in the world, practically daring people to roll up their sleeves and—c’mon!—try their luck at the sucker. And since her twenties, Le Guin had been slowly but surely translating the Tao Te Ching herself for modern readers, while keeping Lao Tzu’s poetry.

Now, there was a tiny problem, namely: she didn’t know Chinese…but she certainly didn’t let that get in her way. She instead utilized existing translations, and collaborated with experts to create a new rendition of the legendary text. And, personally, it’s one of the most approachable, enjoyable, and satisfying. Here’s a snippet where I think Le Guin beautifully highlights Lao Tzu’s thoughtfulness (and sense of humor):

Thirty spokes

meet in the hub.

Where the wheel isn’t

is where it’s useful.

Hollowed out,

clay makes a pot.

Where the pot’s not

is where it’s useful.

Cut doors and windows

to make a room.

Where the room isn’t,

there’s room for you.

So the profit in what is

is in the use of what isn’t.

The Tao Te Ching is one of the most translated works in the world, practically daring people to roll up their sleeves and—c’mon!—try their luck at the sucker. And since her twenties, Le Guin had been slowly but surely translating the Tao Te Ching herself for modern readers, while keeping Lao Tzu’s poetry.

Now, there was a tiny problem, namely: she didn’t know Chinese…but she certainly didn’t let that get in her way. She instead utilized existing translations, and collaborated with experts to create a new rendition of the legendary text. And, personally, it’s one of the most approachable, enjoyable, and satisfying. Here’s a snippet where I think Le Guin beautifully highlights Lao Tzu’s thoughtfulness (and sense of humor):

Thirty spokes

meet in the hub.

Where the wheel isn’t

is where it’s useful.

Hollowed out,

clay makes a pot.

Where the pot’s not

is where it’s useful.

Cut doors and windows

to make a room.

Where the room isn’t,

there’s room for you.

So the profit in what is

is in the use of what isn’t.

When Oscar met Chuang Tzu…

As I delved into Le Guin’s background with Taoism, I discovered that she’s far from the only hero of mine to be enamored by the philosophy. Perhaps most surprising to find is one of my favorite writers, Oscar Wilde. He even wrote a review of an English translation of the Chuang Tzu (the title and author’s name, as Wilde says, “must carefully be pronounced as it is not written”).

And, in short, Wilde was clearly absolutely charmed and intrigued by what he read. Like teenage Le Guin finding a common anarchist in Lao Tzu, Wilde saw an exciting rabble rouser in the ancient writer Chuang Tzu: “He would be disturbing at dinner-parties, and impossible at afternoon teas.”

It’s hard to say how much Chuang Tzu directly influenced Wilde’s life, if at all. But it’s easy to see how Lao Tzu, Chuang Tzu, Le Guin, and Oscar Wilde all shared some similar thoughts, and would probably get on fabulously. In fact, as blogger Heidi C. Parton has pointed out, some of Oscar Wilde’s famous witty quips would be eerily familiar to a Taoist:

Chuang Tzu wrote, “What starts out being sincere usually ends up being deceitful.”

…Or, as Oscar Wilde put it, “A little sincerity is a dangerous thing, and a great deal of it is absolutely fatal.”

As I delved into Le Guin’s background with Taoism, I discovered that she’s far from the only hero of mine to be enamored by the philosophy. Perhaps most surprising to find is one of my favorite writers, Oscar Wilde. He even wrote a review of an English translation of the Chuang Tzu (the title and author’s name, as Wilde says, “must carefully be pronounced as it is not written”).

And, in short, Wilde was clearly absolutely charmed and intrigued by what he read. Like teenage Le Guin finding a common anarchist in Lao Tzu, Wilde saw an exciting rabble rouser in the ancient writer Chuang Tzu: “He would be disturbing at dinner-parties, and impossible at afternoon teas.”

It’s hard to say how much Chuang Tzu directly influenced Wilde’s life, if at all. But it’s easy to see how Lao Tzu, Chuang Tzu, Le Guin, and Oscar Wilde all shared some similar thoughts, and would probably get on fabulously. In fact, as blogger Heidi C. Parton has pointed out, some of Oscar Wilde’s famous witty quips would be eerily familiar to a Taoist:

Chuang Tzu wrote, “What starts out being sincere usually ends up being deceitful.”

…Or, as Oscar Wilde put it, “A little sincerity is a dangerous thing, and a great deal of it is absolutely fatal.”