It’s Just Us: The Need For More Trans Stories

Today is The Human Rights Campaign’s National Coming Out Day, and to celebrate we are spending the day featuring LGBTQ+ voices. Enjoy all the posts here!

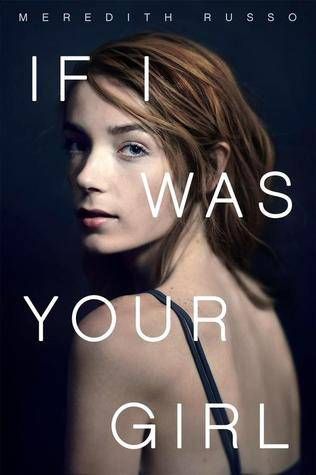

This is a guest post from Meredith Russo. Meredith was born, raised, and lives in Tennessee. She started living as her true self in late 2013 and never looked back. When she’s not busy writing, she can be found reblogging pictures of cats and babies, reading high literature (and definitely not fanfiction and fantasy novels), arguing with strangers about social justice, and, of course, raising her two amazing children, Vivian and Darwin. Follow her at @mer_squared.

The night air in Orlando was thick with humidity and mourning as Alex Gino and I left the convention center and called a taxi. Everyone at the conference was acutely aware of what had happened only days before, and the atmosphere was a bizarre mixture of celebration and resentment. Everyone in attendance, librarians and authors alike, sported rainbow pins, there were rainbow banners everywhere, the names of the dead were on everyone’s lips, and it was certainly a breath of fresh air as a person who grew up in the South, but it was hard not to notice that these affirmations only ever seemed to follow death, hard not to wonder what the world would be like if we talked about queer lives, black lives, poor lives, immigrant lives while they’re still alive, if these funerary celebrations would no longer be necessary. Thinking these things made me feel bitter and ungrateful, but when you’re trans and the only day truly dedicated to you is a mass funeral it’s difficult sometimes not to be cynical.

We didn’t discuss this as we hopped in a cab and asked the driver for restaurant recommendations—there was no need. To be trans is to live in the company of ghosts, a constant balancing act of respecting the dead and refusing to let them drag you into their world. Instead we discussed future projects, the rigors of travel and convention appearances, the politics of the publishing industry, the most bizarre aspects of life as an author, the surreality of suddenly realizing that you’re a public figure. We discussed favorite movies and dating and RVs. We guzzled margaritas on the company dime and took selfies. We lamented the politics of urination.

I can’t speak for Alex, but I never wanted to represent my community. I just wanted to write a nice love story about a trans girl in the south finding herself and hopefully help some young trans people along the way. I’m not spokesperson material. I’m a nervous, impulsive wreck on my best days. And then there’s the dread that I’ve already saturated the market, that nice, liberal cis people around the globe will read my book, congratulate themselves that they’ve done their part and opened their minds, and move on. This fear isn’t unfounded. Most networks’ response to the idea of an If I Was Your Girl television series has been a shrug, followed by, “We’re already working on our trans story.”

Because you only need the one, right? Because, on a certain level, it’s impossible not to think that we’re a fad, a passing fancy, and in a year or two we’ll fade back into the obscurity of set dressing and magical, tragic mentorship. And sometimes I can’t help feeling like I’ve contributed to that, and that’s when impostor syndrome rolls in like a nauseous fog. If this really is the case, if my book is one of only a few shots trans people will get at telling our own stories on a major platform, I don’t think I’ll ever be able to shake the feeling that someone else could have done it better. What could Casey Plett or Imogen Binnie have done with my platform? Ryka Aoki? Sybil Lamb? What could Rae Spoon or Everett Maroon have done with access to my resources and my audience? There are so many trans writers out in the wild with, in my opinion, much more skill and much more to say than me, and yet here I am. How do you cope with that?

Here’s how I’ve chosen to cope: Don’t just read my book, and don’t just read Alex’s. Don’t read one book and feel satisfied that now you understand trans people, now you get it. Trans people are people first and foremost, and no one story can contain the multiplicity of our lives. Given the choice between a trans story written by a cis person or a trans story written by a trans person, always choose the latter. Don’t let us be a fad. Don’t wait to discuss us until we’re dead and then feel satisfied that you’ve done your part. Don’t let it be just us, because lord knows I’ve got enough on my mind without that albatross. Do me this favor and I promise you won’t regret it.