Why TO KILL A MOCKINGBIRD Isn’t A YA Novel

This post is part of our Harper Lee Reading Day: a celebration of one of the most surprising literary events of our lifetime, the publication of her new book, Go Set a Watchman. Check out the rest right here.

____________________

Like many other readers, I sat down recently to revisit Harper Lee’s To Kill A Mockingbird. I remember virtually nothing from the book — I can hardly even remember when I read it, but I know I picked it up one summer in my teen years on my own and I know we read it in an English class in high school. I wanted to revisit Lee’s classic in part to prepare for the release of Go Set A Watchman and in part because I could not wrap my head around the claims I’ve seen made again and again and again and again and again that in today’s market, it would be sold as a young adult (YA) novel.

Before explaining why that claim is far-fetched, perhaps it’s worth discussing what defines YA.

First, and perhaps the most standard response to what defines a YA novel, is that it’s a book written for and marketed to young adults. Knowing a bit about the book industry as it is, as well as how writing itself goes, this definition is pretty generous. It suggests that all writers know exactly who their intended audience is. In many cases, they do; often, though, writers are telling the story in the way it’s best told, regardless of who they anticipate the age range of readers may be.

It’s common for a book to be repackaged or marketed in a way that differs from what the author envisions or anticipates. What an author may see as a work of literary fiction may, in fact, be better marketed and sold as young adult by the editor or larger publicity and marketing departments at a publishing house. Well-known titles like Markus Zusak’s The Book Thief and Mark Haddon’s The Curious Incident of the Dog in the Night-Time have been packaged and marketed as both adult and YA, both in the US and overseas.

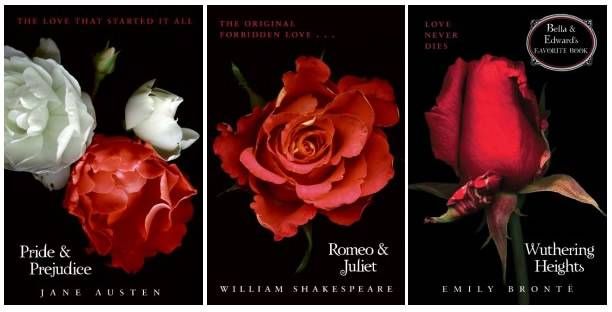

Likewise, depending on the market — a ~nebulous~ force that has significant power in determining the success and/or lack of success for everything relating to books — books can be rebranded or repackaged to fit whatever trend is all the rage. Take a look, for example, at how a handful of classics have been repackaged:

Hazard a guess as to when these book covers hit shelves and where a reader may stumble upon them in a bookstore. If your answer is 2007 to 2010 and the young adult section, then you’re well aware these covers mimic the phenomenally powerful and popular Twilight series.

But just because those covers hop the trend doesn’t mean they’re YA books. While many would (rightly) argue that Austen, Shakespeare, and Bronte’s titles above published well before we had a designated young adult category, given their themes, their writing styles, and their intended readership — which, yes, even back in the day was more likely than not adults, rather than teenagers — they’re adult novels/plays. The themes can absolutely be grasped and parsed by teenagers, but they were likely not intended for teenagers to be the primary audience.

So if authorial intent isn’t always known and instead it’s editors and the publishing house at large that make decisions about a book’s intended readership, where does that put Lee’s novel?

Before getting there, two more elements of what makes a YA novel are worth elucidating: protagonist’s age and the story’s voice.

Many casual readers of YA, as well as naysayers of YA, tend to see these books as ones where the primary cast of characters falls in the 12-18 age range. And for the most part, this is true. There are some notable exceptions: books like Rainbow Rowell’s Fangirl and Gayle Forman’s Just One Day/Just One Year duology feature characters who are 19 and over 20. Then there are books which feature adults in their cast of characters, like Dead Connection by Charlie Price. Rarely, if ever, do we find YA books featuring characters younger than 12, even in an ensemble. Those books generally fall under the middle grade umbrella.

Novels categorized as adult don’t have such rigidity about them when it comes to age of the characters. Books like Everything I Never Told You by Celeste Ng offers a cast of characters, with one of the primary plots centered around a teen girl; The Book of Unknown Americans by Cristina Henriquez offers a varied-age cast, too, with a major thrust of the story about teens; and perhaps most well-known, Jodi Picoult’s books, including and especially 19 Minutes, are adult novels but with many teen-age protagonists. Picoult is especially an interesting example here because her books are marketed and sold in the adult category, but she’s frequently offered as a great crossover read with tremendous appeal for teens.

If intended audience and age can’t be the ultimate determining factors in what is or is not a YA novel, what’s left to make decisions about a book’s categorization?

When it comes to YA, voice is perhaps the biggest deal maker and breaker. Does the book feel authentically young adult? What does “authentically young adult” even mean? If YA books are about firsts or coming of age, then what separates bildungsroman titles placed in the adult section rather than the YA one?

Voice is tricky, it’s subtle, and it’s a bit like porn: you know it when you see it.

Debates rage within the YA community all the time about various titles marketed and sold as YA, as sometimes a title feels like it’s much more adult or much more of a middle grade novel than one truly “meant” for young adult readers. The reason these debates happen is often this voice concept. Does the book read like something YA? Is the style, the approach, the perspective, and the execution what one anticipates when opening a YA novel?

Though not a rule, generally speaking, “voice” in YA is one that’s immediate, sharp, carefully paced, and doesn’t feel too smart, preachy, or grown-up. Because YA is about the growing up process — the highs and lows — it shouldn’t be too reflective, didactic, or approach big themes with universality. YA is often about how those big universal concepts impact the individual right here and right now.

Now that the waters are murky and there’s clearly not a clear definition of what is or is not a YA book, doesn’t that mean there’s ample room for a book like Lee’s to fit? Yes and no.

The flexibility of the category suggests that Lee’s book could fit as YA. But just because it could fit, doesn’t mean that it does nor that it should.

To Kill A Mockingbird is told through the eyes of Scout, as we all know, but Scout isn’t the age people seem to think she is. She’s telling the story through reflection as an adult, and her perspective throughout the story is through that adult-remembering lens. This comes out on the first page of the novel, but it’s such a small element of the greater story that it’s easy to forget: “When enough years had gone by to enable us to look back on them, we sometimes discussed the events leading to [Jem’s] accident.”

From there, readers are launched back in time to Scout’s year in first grade and onward towards her eighth birthday. Even if we allowed enough latitude to let an eight year old perspective fly under the YA label, the fact that her adult self is reflecting upon her experiences as a child — a child, not a teenager — this is a huge stretch for any definition of YA fiction. Perhaps many could argue that because the main character telling the story is younger this book is more middle grade than YA anyway, but it’s that issue of perspective and voice that needs to be taken as further evidence this wouldn’t be a YA book in today’s world.

The focus in Lee’s book is that of justice and prejudice. These are hugely universal themes that emerge in books of all categories. But because they’re explored in their universality in To Kill A Mockingbird, Scout isn’t the one learning the hard lessons first hand. She’s observing them, offering an almost too-rosy perspective. What happens at the trial especially showcases this: we don’t have the story filtered through Scout’s own immediacy. Instead, she’s relying the play by play with an innocence that’s not biased. Not because she doesn’t have beliefs about what’s going on, but rather, because this isn’t her story. It’s her reflection upon a story. She is the vessel through which it’s told, rather than the one doing the telling.

Two smaller pieces of the story struck me in this reread in a way I didn’t anticipate, and both of them further solidified to me that this isn’t — and wouldn’t be — a YA book.

The first is how much reverence there is for Scout’s innocence. Because the story is a reflection, rather than immediate, the games that Scout and Jem play with the Radleys is seen as that: games. It’s not reflected upon as cruel, nor is there a pause that occurs in the immediacy from Scout, Jem, or the adults around them about what they’re doing. It’s childish, seen as childish, from her adult point of view in memory. The childishness is romanticized, almost, and it’s certainly accepted as a thing kids just do. In today’s YA, an act like this which takes up as much page time as it does would have far more reflection and nuance to it — it wouldn’t be seen as fun and games, but rather, there would be some bigger, meatier purpose for it in order for it to carry the weight it does in the novel. Lee justifies it here, but her justification is in the message of the innocence of childhood, rather than a parsing of what something like this might mean in terms of growing up.

Remember the magical hole in the tree, the one where Scout and Jem found presents? After they found a soap rendering of them and the hole was cemented up, there’s almost no reflection about what happened or who did it. As readers, we have to pull out that it was Boo Radley involved in this; rather than allow herself to be imaginative or playful or full of wonder or even fear, Scout’s account of this particular series of events is straightforward, even if it’s not spelled out for the readers. Lee writes this well. She wants readers to have to work for it, and she wants Scout to have to work for it, too. However, that “working for it” means we lose much of what makes a YA novel’s voice what it is — the experience of immediacy. Even historical fiction and even YA novels told in reflection offer this immediacy. The emotions become palpable, real, and sometimes even visceral.

We don’t get that with To Kill A Mockingbird. Rather, we walk away with meaty takeaways told through the eyes of an adult looking back at her childhood, rather than a child filtering those experiences through her own intellectual and developmental milestones.

To Kill A Mockingbird is a classic and it’ll remain a mainstay in fiction forever, without question. It will be a book teenagers read in high school, and it will be a book that parents will find completely okay to hand to their teens as appropriate reading — whatever that means — in part because the book evokes such nostalgia. Lee does this by offering such solid themes and a narrator who can render them in a voice that’s young and still unaffected by the greater challenges in the world.

Lee’s book, as much as it’s about prejudice and racism, is a book about the innocence of childhood. It’s about the ways the world has yet to impact you on a personal level. It purposefully evokes nostalgia, starting right on page one.

But it’s those very things that make this book one that doesn’t fit the curves and paths of YA as it stands today. YA books dive deep into those affections; the main characters, who are well beyond first or second or third grade, are often world-weary, even if they’re optimistic about the futures ahead of them. Their perspectives shade every interaction, and we as readers see this clearly. There’s not standing back nor holding back.

I don’t believe this book would be seen as YA, even if it were pitched in today’s market. It’s an adult literary titles through and through, even as it appeals significantly — “crosses over” — to young adult readers. While it may seem arbitrary to argue this point, labels are in and of themselves contentious. They are and they aren’t arbitrary.

That is, of course, why defining “YA” is itself a challenge.