How I Overcame My Fear of Reading Contemporary Poets

This content contains affiliate links. When you buy through these links, we may earn an affiliate commission.

When I was a prospective student visiting the creative writing department at my now alma mater, an upperclassman asked me who my favorite poet was. I said Emily Dickinson. He asked if I had any favorite contemporary poets, but I couldn’t name one—I didn’t read contemporary poetry. I thought free verse was nothing but arbitrary line breaks in formless drabbles that were also so esoteric and inaccessible that I couldn’t possibly be expected to understand or enjoy them.

Seven years later, I not only have several favorite contemporary poets, but poetry collections make up nearly 20 percent of the books I read. Here’s how that happened.

Even after that awkward conversation, I had no plans to start reading contemporary poetry until the first day of my Introduction to Creative Writing class freshman year. Dr. Smith—the department chair—told us we would each be writing six poems. That was more poems than I’d written in my life up to that point.

He gave us a prompt and some guidelines: no rhyming, no abstract generalities, no cliché word choices. Ground your poems in strong nouns and verbs rather than adjectives and adverbs. Don’t simply report on a feeling, evoke it using concrete language that puts the reader in the experience. Above all, avoid the crime of anonymity—write the poem that only you can write, offering your unique voice and perspective. Universal truths emerge from the particulars of an experience, so if you want to write a poem about mothers, don’t describe them as a concept—tell me about yours.

I agonized over that first poem. Eventually I just wrote a prose paragraph and put line breaks in wherever I felt like it until I thought it looked like a poem. During workshop, Dr. Smith complimented the specifics I’d captured, but he had a lot to say about the form:

Even after that awkward conversation, I had no plans to start reading contemporary poetry until the first day of my Introduction to Creative Writing class freshman year. Dr. Smith—the department chair—told us we would each be writing six poems. That was more poems than I’d written in my life up to that point.

He gave us a prompt and some guidelines: no rhyming, no abstract generalities, no cliché word choices. Ground your poems in strong nouns and verbs rather than adjectives and adverbs. Don’t simply report on a feeling, evoke it using concrete language that puts the reader in the experience. Above all, avoid the crime of anonymity—write the poem that only you can write, offering your unique voice and perspective. Universal truths emerge from the particulars of an experience, so if you want to write a poem about mothers, don’t describe them as a concept—tell me about yours.

I agonized over that first poem. Eventually I just wrote a prose paragraph and put line breaks in wherever I felt like it until I thought it looked like a poem. During workshop, Dr. Smith complimented the specifics I’d captured, but he had a lot to say about the form:

- Don’t let Word automatically capitalize your lines for you—make all your capitalization intentional.

- Don’t waste the ends of your lines on weak words.

- Use your line breaks to create emphasis, to surprise your reader, to suggest alternate interpretations.

***

The next semester, the upperclassman from my first visit chose one of my poems for publication in our school’s literary journal. After that, poetry began sneaking into my life again. I’d be journaling, like any devout fan of Joan Didion or David Sedaris, and occasionally my pen would slip thoughts into stanzas. Terrible, cliché poems never to see the light of day, of course, but I was flexing the muscle. Experimenting with how form could add shades of meaning to language. Guest poets would visit and give seminars and readings. I’d print my most palatable poems for their workshops, begrudging the fact that poetry was easier to critique in such a group than prose. The poets—Catherine Pierce, Jeanine Hathaway, and others—spouted pithy wisdom in these meetings that stayed with me, though. “Pretend each word in a poem has to pay to be there,” said one poet. “Trust that your reader is smarter than you,” said another. “Nobody wants their hand held.” One named honesty as a key principle in his aesthetic philosophy: “Once I get a whiff of pretense, I’m out.” All of this advice proved useful for my prose, and eventually I began attending the workshops without grudge. I’d sit in the audience at their readings, listening to the cadence of their words, and wish I had their poems in hard copy so I could follow along and see their line breaks.***

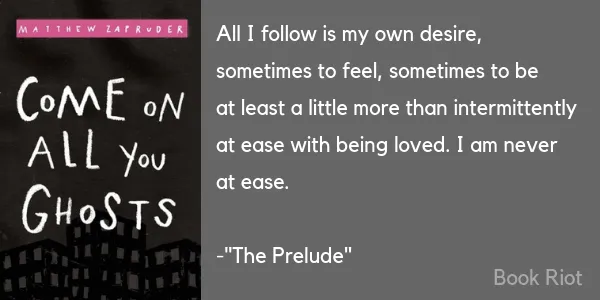

Dr. Smith always insisted that poetry was a crucial part of a writer’s diet. “Everyone should read at least one poem every day,” he said. “I always keep a collection on my bedside table for easy access.” Never gonna happen, I thought. Yet while perusing the stacks of my college library one day, my gaze stuck on a copy of Come on All You Ghosts by Matthew Zapruder. Intrigued by the title, I flipped it open. Instead of finding the poems esoteric and inaccessible, I got chills. This stanza from “The Prelude” hit me hard: Each line was an experience in itself. The end words were not wasted. The whole poem evoked in me a certain feeling I couldn’t quite place. I turned to “Poem for Hannah,” which ends with the lines, “You were born to feel a way / you don’t have a word for.” Huh. I thought. Suddenly contemporary poetry was making me feel a way I didn’t have a word for.

During a systematic culling of old books, the library threw out a crumbling paperback copy of Alice Walker’s poetry collection Goodnight, Willie Lee, I’ll See You in the Morning. I rescued it from the trash and found a poem called “Never Offer Your Heart to Someone Who Eats Hearts.” The vivid imagery and concrete metaphors evoked a visceral sense of anger and betrayal in my gut over a heartbreak I didn’t even have. Touché, Alice Walker. I thought. Touché.

Each line was an experience in itself. The end words were not wasted. The whole poem evoked in me a certain feeling I couldn’t quite place. I turned to “Poem for Hannah,” which ends with the lines, “You were born to feel a way / you don’t have a word for.” Huh. I thought. Suddenly contemporary poetry was making me feel a way I didn’t have a word for.

During a systematic culling of old books, the library threw out a crumbling paperback copy of Alice Walker’s poetry collection Goodnight, Willie Lee, I’ll See You in the Morning. I rescued it from the trash and found a poem called “Never Offer Your Heart to Someone Who Eats Hearts.” The vivid imagery and concrete metaphors evoked a visceral sense of anger and betrayal in my gut over a heartbreak I didn’t even have. Touché, Alice Walker. I thought. Touché.

***

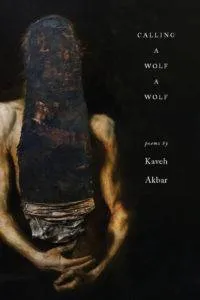

Senior year, I signed up for Dr. Smith’s advanced poetry workshop and arrived on the first day with an audit form in hand. “Not risking my honors status on the strength of my poetry,” I told him. He signed my form, delighted I’d come around to poetry at last. Part of the class was reading fifty contemporary poems and writing a response to each one. “You can write as much or as little as you want,” he said. “Copy down lines you liked, comment on word choice, note any poetic devices used, describe the feeling the poem evoked—or failed to evoke!—when you read it.” Through this exercise, I finally began to understand Dr. Smith’s philosophy that poetry should be part of a well-rounded literary diet. These fifty poems helped me understand my aesthetic sense, but they also made me feel something. The ending of Diane Seuss’s “Jesus, with his cup” left me with another kind of unnameable feeling: “Even the mayor’s wife sipping from a teacup / wreathed in Banded Peacock butterflies wonders, in her loneliness, / why me? Why this cup?” I caved and decided to try the Poem-A-Day diet as provided by an email subscription through the Academy of American Poets. Admittedly some poems felt esoteric and inaccessible, reinforcing my early fears about reading contemporary poets. But others I liked, and some I even loved. Poetry became the bulk of my literary intake when I moved to Spain to teach English; I had limited access to English books in my local library, but every day I had a poem in my inbox. Every day I read them on my bus ride home through the Basque countryside. It became a meditative ritual, a restorative literary snack after a hectic day of teaching. During this time I encountered “Heavy” by Hieu Minh Nguyen. “I think the life I want // is the life I have, but how can I be sure?” it reads. Far from home on an expat year full to bursting with loneliness and adventure, those words resonated deeply. I returned to America with a serious craving for poetry, but I didn’t know where to start with actual collections. Then John Green recommended Kaveh Akbar’s 2017 debut Calling a Wolf a Wolf, and my small Midwestern library happened to have a copy. I read it slowly, a poem or two at a time, filled with the sense that to read them all at once would be a kind of gluttony. Those tools I’d been taught to look for when reading poetry? Akbar used them all, and more, with acumen and skill.

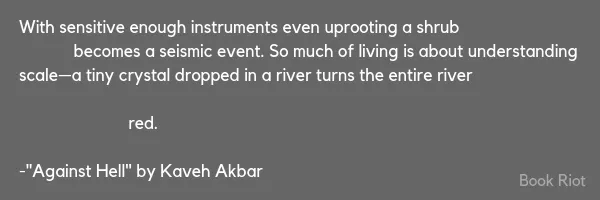

Take this stanza from “Against Hell,” a perfect example of how each line can be an experience—a poem—unto itself:

I returned to America with a serious craving for poetry, but I didn’t know where to start with actual collections. Then John Green recommended Kaveh Akbar’s 2017 debut Calling a Wolf a Wolf, and my small Midwestern library happened to have a copy. I read it slowly, a poem or two at a time, filled with the sense that to read them all at once would be a kind of gluttony. Those tools I’d been taught to look for when reading poetry? Akbar used them all, and more, with acumen and skill.

Take this stanza from “Against Hell,” a perfect example of how each line can be an experience—a poem—unto itself:

The second line can be read straight through to the next as a sentence, but the line break also gives us the phrase “So much of living is about understanding,” which resonates beautifully on its own. But why stop there? You can also read part of the line as a loop to get the phrase: “understanding becomes a seismic event.”

Understanding this poem, and figuring out how to enjoy the work of contemporary poets in general, became a seismic event for me. Looking back, this collection was the gateway to my full-fledged obsession, the book that solidified the potential of this form to move me in the way that prose always had. Akbar wrote the collection as a recovering alcoholic, finding solace in committing himself to the art form.

“The fact that poems exist is the load-bearing gratitude upon which I have built my life,” he explained in an NPR interview. “And what do you do with gratitude when it piles up? You have to push it outwards.”

That gratitude’s piled up over the past few years for me, so here I am pushing it outwards. Not only am I no longer afraid of reading contemporary poets, I can’t imagine my life without them. Thanks, Dr. Smith. You were right all along.

The second line can be read straight through to the next as a sentence, but the line break also gives us the phrase “So much of living is about understanding,” which resonates beautifully on its own. But why stop there? You can also read part of the line as a loop to get the phrase: “understanding becomes a seismic event.”

Understanding this poem, and figuring out how to enjoy the work of contemporary poets in general, became a seismic event for me. Looking back, this collection was the gateway to my full-fledged obsession, the book that solidified the potential of this form to move me in the way that prose always had. Akbar wrote the collection as a recovering alcoholic, finding solace in committing himself to the art form.

“The fact that poems exist is the load-bearing gratitude upon which I have built my life,” he explained in an NPR interview. “And what do you do with gratitude when it piles up? You have to push it outwards.”

That gratitude’s piled up over the past few years for me, so here I am pushing it outwards. Not only am I no longer afraid of reading contemporary poets, I can’t imagine my life without them. Thanks, Dr. Smith. You were right all along.

***

For more poems that fulfill (and expand on!) this set of aesthetic principles, check out this post on the 15 stanzas that made me fall in love with contemporary poetry.