Into Their Own Hands: Copaganda in Superhero Comics

“Policemen, judges, Government officials and respected institutions shall never be presented in such a way as to create disrespect for established authority.”

Thus reads Part A(3) of the Comics Code Authority, created in 1954. This section survived the Code’s 1971 revision with an extra sentence added: “If any of these is depicted committing an illegal act, it must be declared as an exceptional case and that the culprit pay the legal price.”

In other words, for a good chunk of comics history, comic books could only depict the police as nice, moral folks worthy of respect. If one did go astray, that was a personal failing, not a systemic one. In the latest parlance, this is called copaganda: the mass media’s insistence that cops are always good guys, and that if a cop has to break the law to uphold it, that’s just how life is sometimes. It certainly has nothing to do with rampant racism in the police force.

Copaganda in superhero comics is as inescapable as leotards and utility belts.

Copaganda and Superheroes: A Persistent Match

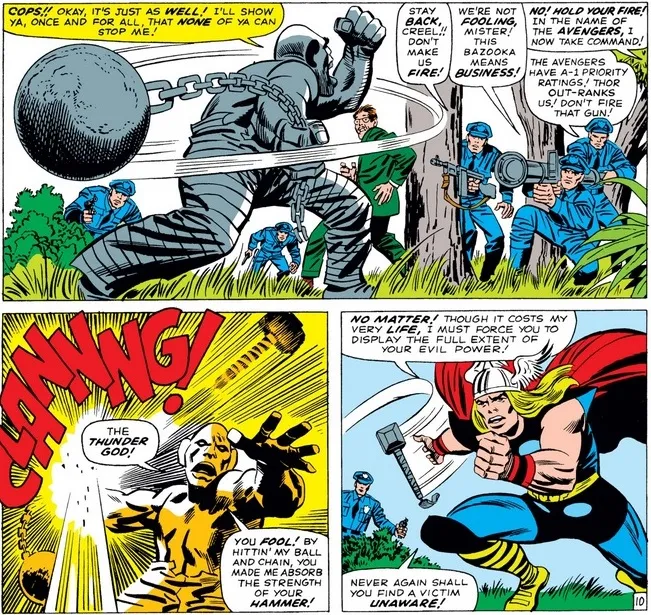

If you read enough comics, you’re familiar with this scene: square-jawed boys in blue try their hardest to hold back a super-powered threat. Valiant as they are, they are no match for the supervillain. Fortunately, a person with a cape or special armor is on hand to take care of things. Once the fight is over, the hero obligingly brings the subdued villain to the nearest precinct for incarceration.

This is what a policeman is in the world of superhero comics: a stalwart representative of the law who can handle ordinary criminals but is generally happy to accept help from the neighborhood superhero when it comes to super-powered threats. Corruption? Prejudice? Grayscale morality? Not here! The most nuance you could hope for was a character like Captain George Stacy, who butted heads with Spider-Man but was still meant to be an upstanding policeman.

Long after the Code lost influence (it was abandoned all together in 2011), comics continued to portray the police in an overwhelmingly positive light. Even Nightwing, which depicted the city of Blüdhaven as a hopeless cesspool filled to the brim with corrupt cops, insisted that Blüdhaven’s situation was unusual and that cops in other cities — including villain-choked Gotham — were much better.

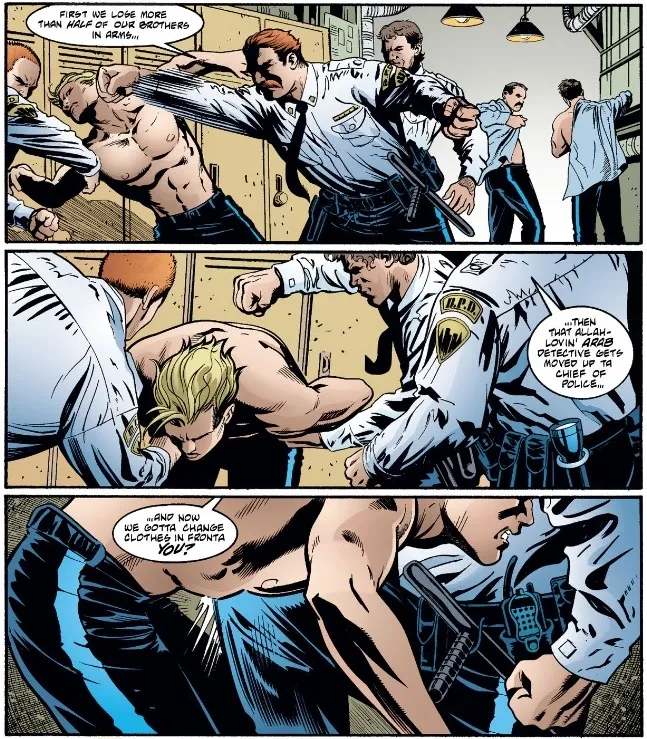

But the comic still manages to tell on itself. Nightwing joins the police department to root out corruption from the inside. (This is a ridiculous plan, because whistleblowing doesn’t work on police departments, but anyway.) After Nightwing scrubs the BPD of every single bad cop, leaving a small but moral group to rebuild, this happens.

These are “the good apples.” These are the good cops who, unlike their peers, never took a bribe or murdered indiscriminately. And they’re a bunch of homophobic, Islamophobic bullies. Sure, Nightwing calls them out for it, but he never questions whether these guys should be on the force or if the clean-up job he did was inadequate. And this is a character who questions and blames himself for everything!

Copaganda in Superhero Comics Today

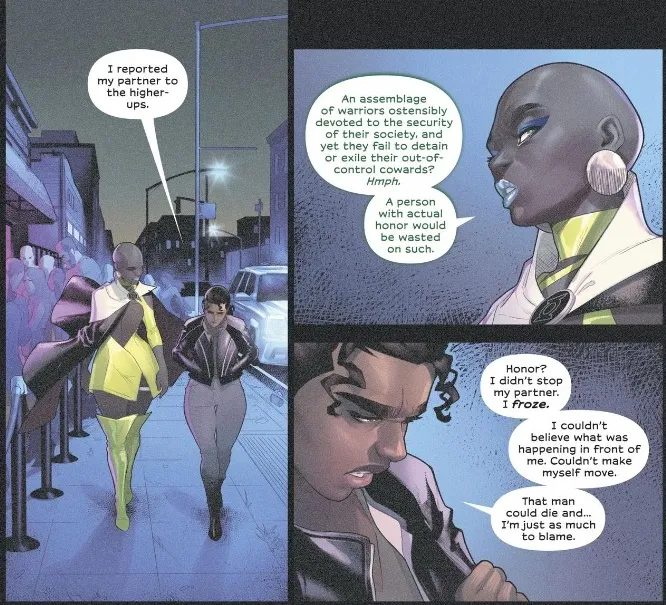

While the high-profile murders of George Floyd and Breonna Taylor made 2020 a turning point for white Americans’ awareness of police brutality, the tide was already changing. Far Sector, published from 2019 to 2021, tackles this issue explicitly: its protagonist, a Green Lantern, goes to an alien world where a corrupt government violently oppresses dissenters. We later learn she is an ex-cop who reported her partner for excessive force and was fired for her association with a Black Lives Matter activist.

Superhero adaptations have also had to change with the times. The CW’s Batwoman had an especially tough time of it: the title character’s father Jacob and ex-girlfriend Sophie were members of a police-like security force, the Crows. Both were depicted as good people with Gotham City’s best interests at heart. Season 1 concluded a mere eight days before George Floyd’s murder; inevitably, Season 2 struck a very different tone.

The Crows suddenly became much more complicated, even insidious. The episode “And Justice for All” featured supporting character Luke Fox, who is Black, getting shot by a white Crow, who justified his actions by insisting Luke was armed. (Luke only had a cell phone.) Both Jacob and Sophie spent the season rationalizing their membership with the Crows (“I want to change the system from within,” etc.). None of their excuses sat well with the new Batwoman, a Black woman with a criminal record and a bad history with Sophie. Ultimately, they couldn’t keep their balance: Sophie quit, and Jacob disbanded the Crows.

While these are admirable moves, it doesn’t address the superhero’s true problem with the police: the very idea of a superhero is itself rooted in copaganda.

The Superhero as Copaganda

The notion that some criminal threats are too serious to deal with lawfully and that someone has to be willing to break the law (and some bones) to ensure “justice” is done, is the hallmark of copaganda. And that’s the underpinning of the superheroic ethos.

Unlike the police, who always care so much about due process (ahem), superheroes are unencumbered by red tape and can operate as they wish. They use their powers or gadgets to spy on suspects, collect evidence, and break into private property — all actions that police officers are supposed to get a warrant for. (Waiting for a warrant only gives the criminals time to get away! We must act now!) And if they have a bad day and take out their frustrations on some unfortunate henchmen once in a while, well, no one cares about henchmen, anyway.

To justify this behavior, comic books have to pit our heroes against the most hardened, irredeemable scoundrels known to man. Never mind that violent crime rates have been steadily falling and that most crimes could be prevented with adequate job opportunities and mental health resources. That’s boring. Besides, if superheroes spent too much time beating up broke, traumatized, and desperate people, most readers (one hopes) would lose sympathy for them real quick. Superhero comics (and other genres, like true crime) profit by ignoring such common, mundane crimes and sensationalizing serial killings and other hyper-violent events.

When a criminal is released from prison, superheroes are immediately suspicious and take preemptive action against the individual — who, again, has served their sentence, just like they were supposed to. Heroes may pay lip service to making a villain “pay their debt to society,” but paying off that debt is made impossible. Supervillains have been built up as such nasty people that the idea of any of them genuinely reforming is now laughable. In superhero comics, criminals who deserve help are rare exceptions. Most are evil for evil’s sake, so they get stuck in a dungeon-like cell in a draconian, unsupportive institution — preferably forever.

This all feeds the idea that the world is filled with monsters who “just want to watch the world burn” and can only be stopped in time if our protectors (whether cop or superhero) stray outside the letter of the law. Who’s going to quibble over a few human rights violations when innocent lives are on the line?

The Future of Copaganda in Superhero Comics

Will we ever see an end to copaganda in superhero comics? It wouldn’t be easy. We would have to redefine almost everything we know about what a superhero is, how they behave, and how they interact with police. One commentator has suggested that superheroes serve as blueprints for a real-life future with a greatly reduced police presence. I can see superhero comics trying to do this more explicitly, but it might take them a while to find a way to do it right: superheroes have often stumbled when exploring new, progressive ideas about society and justice.

Even if every single publisher and movie studio started working towards eradicating copaganda from superhero stories tomorrow (and they won’t), it would take a very, very long time for everyone to adjust and to wipe every trace from the genre. What are we supposed to do in the meantime? Give up superheroes? I sure hope not, because I’m not doing that. As with any media, it’s important to recognize and call out propaganda of all types when we see it, and to support projects that grapple with copaganda or take superheroes in fresh, more critical directions. (The Polygon article I linked to has examples, including the amazing Far Sector.)

In the end, it’s on every fan to decide for themselves what they’re comfortable tolerating. But it’s on all of us to be active participants in the media we consume, especially the media we love best.

Read about the role of copaganda in crime novels here.