Comic vs. Book: TO KILL A MOCKINGBIRD

Everyone knows that books can be adapted into movies. It happens all the time. But did you know they can be adapted into graphic novels, too? In this series, I’ll be taking a look at classic novels and their illustrated counterparts to determine what each did well, what each did wrong, and how they approach the same story decades apart and in such different media.

The subject for our inaugural duke-it-out session is, of course, the 1960 classic To Kill a Mockingbird! I’m excited! Are you excited?

The Book

To Kill a Mockingbird by Harper Lee became an instant hit, even spawning an Oscar-winning film adaptation two years after its publication. The plot is as follows, and here be spoilers:

Over the course of two years in the 1930s, young Scout Finch and her brother Jem are forced to reckon with the unpleasant realities lurking beneath the surface of genial Maycomb County, Alabama. Most notable of these events is the wrongful conviction of Tom Robinson, a Black man falsely accused of raping an impoverished white woman with an abusive father, Bob Ewell. This inevitable miscarriage of justice comes despite the best efforts of Scout’s father Atticus, a lawyer, to save Tom. Scout also nurses an obsession with a mysterious neighbor, Arthur “Boo” Radley, who hasn’t left his house in years. It all comes to a head one autumn night, when Boo finally leaves his house to save the Finch children from a vengeful Bob Ewell.

Rereading the novel for this article, I was struck by how affable it is. Scout is a witty narrator and an enjoyable protagonist whose limited, youthful perspective leaves a lot unsaid. The older you are, the easier — and more painful — I think it is to fill in those gaps.

The final chapter brought tears to my eyes as Scout follows Atticus’s advice to “stand in [another person’s] shoes and walk around in them,” and imagines what the past two years must have been like for Boo, watching the goings-on from his window.

Despite knowing the story so well, and despite its flaws, I enjoyed going along for the ride once more. I do believe the phrase “Hey, Boo” is seared into my soul. I can’t think of a higher compliment to give a book than that.

The Comic

Though undoubtedly a classic, To Kill a Mockingbird‘s legacy has become more complex in recent years. It delivers its antiracism message through outdated, racist tropes that perhaps make it inappropriate as required school reading. On the other hand, that message — as well as its commentary on adjoining issues, such as classism and lack of access to healthcare — is evergreen and worth a second look.

With all that in mind, I wondered if 2018’s To Kill a Mockingbird: A Graphic Novel, adapted and illustrated by Fred Fordham, would remain faithful to the original’s flaws as well as its strengths. Or would it in some way update the story to account for modern criticisms, perhaps by spending more time examining events from the Black characters’ perspectives?

Turns out, it’s the former: there’s a note in the back of the book stating as much. That’s probably for the best, given other recent attempts to remove offensive material from old books. I do commend the comic for being so faithful to the novel: it cuts only a few minor scenes — I don’t think I’d have missed them if I hadn’t just reread the book — but otherwise keeps the entire story more or less intact. Given that, I really shouldn’t have been surprised that the comic (273 pages) is almost as long as the novel (323 pages).

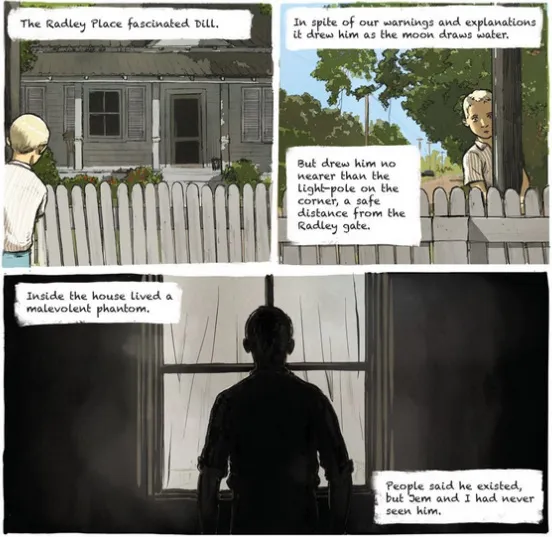

The only new contribution the comic makes to the story is its art. On that front, I have mixed feelings. It has a rough, rustic quality to it — you can see pencil marks in some panels — that is appropriate for a story set in rural, Depression-era Alabama. Overall, the art is pretty, particularly the backgrounds.

On the other hand, I was not a fan of how the faces were drawn: the characters’ expressions felt flat a lot of the time, muting the more emotional moments, like during Tom Robinson’s testimony. I couldn’t help remembering this scene’s film version, where actor Brock Peters, as Tom, retains a stoic reserve even as he starts crying while testifying. That’s not a fair comparison — this is adapting the book, not the movie — but since the film was my introduction to this story, it’s just where my brain goes.

(If I’m going to bring up the movie, I should give the comic credit for accurately depicting Tom’s disability, whereas Peters was able-bodied and faking it.)

I also must say that something about everyone’s eyes reminded me of Junji Ito’s work. “Horror manga” is not the vibe I expected or wanted for this story.

The only part I felt they did better than the original was when the jury convicts Tom. In the novel, Scout closes her eyes during this moment. In the comic, we are forced to view Tom’s reaction head-on as four panels, one atop the other, show us his fear, his anguish, his grief, and finally his resignation.

The Takeaways

Personally, I did prefer the novel for its additional material and for the fact that I could imagine the action for myself in the way I liked. The art in the comic just didn’t live up to the images I could create for myself — or, often, the images implanted in my brain by the film version years ago. That’s a pretty big sin: a graphic novel that can’t nail the graphics isn’t doing its job.

But again, the comic is not bad by any means, and if you enjoy graphic novels or want to (re)experience the story in a new way, I don’t think you’ll be disappointed by it. In fact, if you like the original, you’ll be very pleased with how much they preserved and how faithful the comic is to it.

The more I immersed myself in this story, the more I longed for the day when it will fall into the public domain. There is so much material to work with here, and I can very easily see people writing novels — graphic or prose — about the Ewells or Tom’s widow Helen. Or maybe they could reimagine the original story from the viewpoint of Calpurnia, the Finches’ maid, or one of the other Black characters who haven’t yet gotten the chance to speak for themselves.

But until then, we can still enjoy the novel and its various iterations — as well as more nuanced books for young people about American racism.