Visit with These Appalachian Memoirs

If you were to walk into my library and look at my shelf of memoirs, you’d see a series of well-worn paperbacks, their rumpled pages underlined and annotated within an inch of their lives. Some of the pages are folded in on themselves, while others feature sticky notes or far too many tabs. One time, a gracious guest commented, “Wow, these are really . . . well loved.”

I can’t help but smile at this often repeated scenario. They aren’t wrong. To me, there’s just something about holding someone else’s story in your hands. These authors have just shared an intimate look into their life with the world. Appalachian stories especially feel like they were written just for me. An Appalachian memoir asks readers to bear witness to a life like no one’s else’s. No singular story can encapsulate an entire region, a place full of millions of stories, each as unique and one-of-a-kind as the next.

Growing up, my grandma would tell me stories about going back up in the holler to visit with folks in her area. The phrase “visit with” usually refers to showing up at someone’s house, often unannounced. If they liked you well enough, they’d offer you a glass of iced tea and you’d sit around for a few hours, talking about anything and everything.

But by the time I was a tween, Appalachian cultural staples like this were disappearing. People started expecting you to call ahead or “make plans.” Responding “I’ll show up when I show up” became an unacceptable answer. Instead of running out back while the adults had one of their porch chats, kids now had soccer, play practice, or chess club. I deeply miss this part of Appalchian culture, especially since I’ve moved away from central Appalachia. Appalachian memoirs give me a chance to sit down and visit with some of my favorite writers.

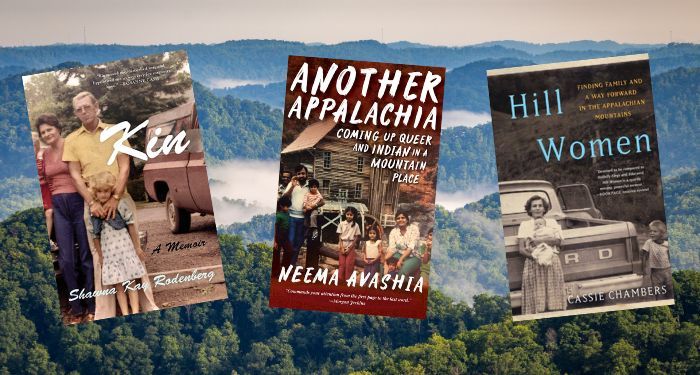

When I read Neema Avashia’s Another Appalachia, I felt transported back to my summers in West Virginia. As I turned the pages of her memoir in essays, I imagined that we’re hiking around in Bitter Southerner T-shirts while she tells me about her childhood growing up as an Indian American “Indolachian.” The descriptions of her neighbors becoming chosen family warms my heart — so many of us have bonus parents and grandparents like that who made a huge impact on our lives. But Avashia tempers her stories of love with the complex lived reality of people you grew up with posting hateful messages on social media about immigrants and LGBTQ+ folks. How could the community she loved, and that she thought loved her, post these terrible messages and somehow not realize they are posting about her? Did they not care after all? Another Appalachia brings you into her thought process as she works through these questions over and over in her mind.

As I made my way through Cassie Chambers Armstrong’s Hill Women, I imagined Armstrong animatedly sharing her life experience over a busy work brunch. Currently, Armstrong lives in the western part of the state and serves in Kentucky State Senate, but her family is from Eastern Kentucky. Armstrong’ parents moved from the family home in the mountains to a bigger town to give them better opportunities. Eventually, Armstrong ended up going to an Ivy League University, graduating law school, and moving back to Kentucky. I turned the pages of her memoir as I sipped my coffee, imagining her sitting right there, describing her thought process through her complex identity; is she still a hillbilly? What does being Appalachian mean for her?

Shawna Kay Rodenberg’s memoir Kin is a cozy up with sort of book. It felt like I had entered a church potluck, and Rodenberg met up with me to gossip over crockpots of overly whipped mashed potatoes and three different kinds of baked beans. As we sit in sticky metal fold out chairs, she tells me about her childhood growing up in a conservative religious commune. After family left that organization and moved back to Kentucky where their family is from, Rodenberg grew up and went to college, which introduced her to a whole new world. Her story is a complex portrait of her family written with love. Familial love can be as messy as it is beautiful. And the way she describes her experience invites you to feel the growing pains of coming-of-age right along with her.

Living in one of the southernmost Appalachian counties, I don’t have the opportunity to sit and visit with people like I used to. But I can grab a memoir — even unannounced and with ice tea in hand — and pour over its pages for hours. I can read these women’s stories and respond in the margins, nodding along and making the appropriate facial expressions at every shocking revelation or plot twist.

The Appalachian memoir presents us with a literary version of a beautiful tradition, preserving a piece of our culture and transforming it into something new in an ever-changing world.