Bat-Mentalities: Batman, Mental Illness, and the Future of Arkham Asylum

That title alone has probably brought some very specific thoughts to mind. Batman’s rogues gallery is a gold mine of criminal insanity and unstable personalities. Even our hero himself is suspect: what mentally healthy adult man dresses as a bat to fight crime? Surely there must be something wrong with all of them?

According to Travis Langley’s Batman and Psychology, 2nd ed. — which puts the Caped Crusader, his allies, and his enemies onto the proverbial psychiatrist’s couch — it’s a lot more complicated than that.

For starters, Langley asserts that Batman, despite popular opinion, does not have a mental illness. The Dark Knight exhibits some symptoms of post-traumatic stress disorder, but not enough to warrant a formal diagnosis. These symptoms (e.g. difficulty expressing emotion) may cause him trouble from time to time, but by and large they do not interfere with his ability to set and accomplish goals and to excel at his job.

When I spoke to Dr. Langley about the depiction of mental illness in Batman comics, he also pointed out that many of the villainous characters defy diagnosis: they are described as “mad,” but their symptoms do not match up with any illness in particular. The reasons for and consequences of this will be discussed later in this article. For now, let’s start with a brief overview of this most complex yet important of topics.

Before Arkham

Arkham Asylum is such a notorious, poorly run hellhole that it has become pop culture shorthand for any prison or institution that cannot help or keep control of its population. Case in point: this 2016 article about New York State’s alleged mistreatment of the mentally ill.

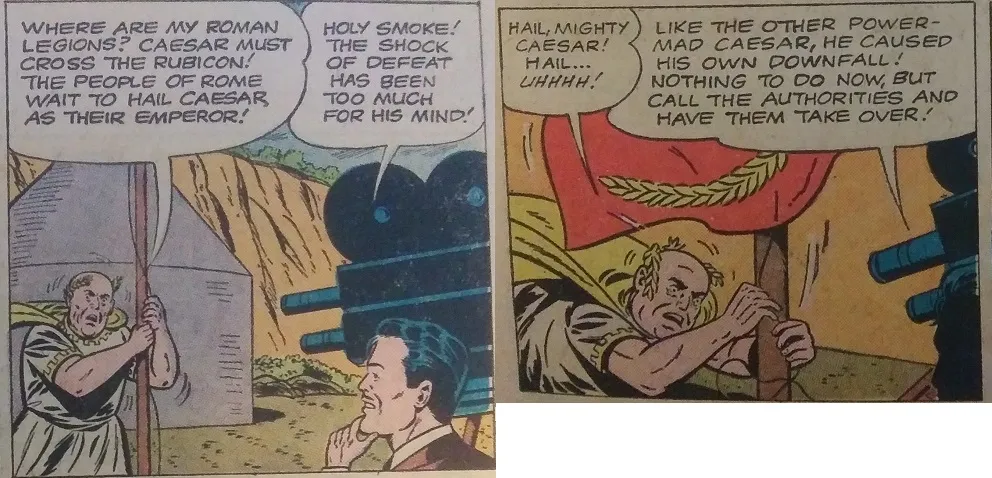

Arkham is so closely associated with Batman’s war on criminals that it’s easy to forget it didn’t always exist: it debuted in the 1970s. Prior to that, his foes were incarcerated in (and frequently escaped from) regular prisons. The idea that mental illness could be influencing their personalities and activities didn’t enter anyone’s mind. A story from Batman #150 highlights this: our heroes tangle with a man who aspires to be a modern Julius Caesar. They describe him as both “mad” and “power mad,” but nothing more specific, so it’s not clear what they think of his mental state. After meeting defeat, “Caesar” loses touch with reality and thinks he really is the famous emperor. The other characters’ apathetic response can be summed up as, “Well, that happens to dictators, I guess.”

This isn’t entirely Batman’s fault, or the fault of his creators. The Comics Code Authority, a draconian self-censorship board founded in the mid-1950s, may have made for a more smiley Batman, but it ironically made him crueler to the people he fought: the Code prohibited any sympathetic portrayal of criminals, so all Batman could do was punch them in the face and send them to jail. That’s why Catwoman disappeared during this period: Batman kept giving her free passes due to extenuating hotness, which became unacceptable by the ’50s.

After the Code lost influence, Batman became ever darker and more violent…but he could acknowledge that some of his opponents were scared or mentally ill people in need of help. It seems counterintuitive to say that Batman treated criminals better post-CCA, given how often he is seen beating the crud out of them or making violent threats. As Dr. Langley told me, Batman likely does this out of pure “impatience”: he cannot legally hold people the way the police can, and he becomes so desperate for answers that he resorts to brutal tactics under the assumption that he, unlike others, will be able to tell if someone is lying just to get Batman to stop dangling them off a roof.

“Batman is so accustomed to being right about so many things that, even though he should know better, he will probably be more prone than average to overestimating his ability to know when people are and are not telling the truth,” Dr. Langley explained.

In the midst of all the beatings, however, there are examples of Batman showing genuine compassion towards his adversaries. So even if he isn’t always nice, he at least has that option now.

When I asked Dr. Langley about how Batman’s approach has changed over the decades, he cited not only the influence of the CCA but also the fact that audiences grew more mature and “more skeptical” as time went on. This process began in the ’60s, when “civil rights, Vietnam, assassinations, and the sheer increase of the number of televisions” bringing current events right into people’s homes forced audiences to reckon with unpleasant realities they hadn’t considered or known about before.

“People began to question heroism itself,” he says, “and so did comic book superheroes themselves.”

So it should come as no surprise that the ’60s Batman TV series, which may have been goofy but wasn’t subject to the CCA’s restrictions, expressed sympathy for numerous villains, most notably Mister Freeze and King Tut. Tut clearly had mental health issues: in his book, Langley speculates that he might have some type of dissociative disorder and possibly delusional disorder. Despite this, he still ended up in Gotham Penitentiary, not a mental health institution.

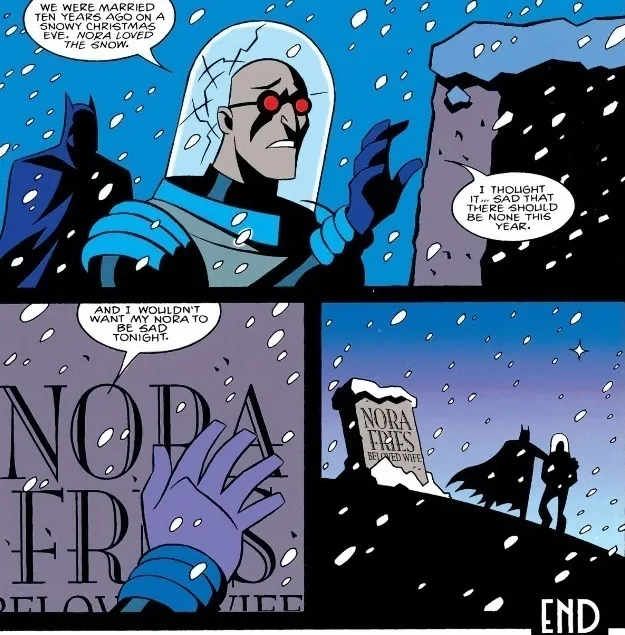

Freeze, meanwhile, was only depicted as having physical health issues (an inability to survive in above-freezing temperatures). He is still depicted somewhat sympathetically: he gives an anguished speech about how he will never again “feel the warmth of a summer breeze.” Batman then implores him to surrender so he can get “medical help.” This opened the door to later versions, which had Freeze embark on a life of crime for his sick wife’s sake and portrayed him as a grieving husband (albeit one who fails to consider his wife’s probable feelings as he takes horrific action on her behalf).

Arkham R.I.P.?

Once Arkham Asylum appeared, it became indispensable. Many of Batman’s more colorful foes are shipped there based on what Langley describes in his book as “ambiguous standards for criminal insanity.” Basically, the standard is: if a person in a funny suit causes trouble, throw them in Arkham.

Worse, there is at least one occasion where someone was imprisoned in Arkham without so much as a psychiatric assessment or a fair trial: Identity Crisis ends with the Atom relegating his murderous ex-wife to Arkham immediately after her confession. There’s something lawless and frightening about the place — which is exactly the point.

Modern stories are starting to analyze how mental illness is portrayed in Batman’s world, if only inconsistently. This includes critiquing the role Arkham plays in helping (or not) stem Gotham’s proliferation of costumed criminals.

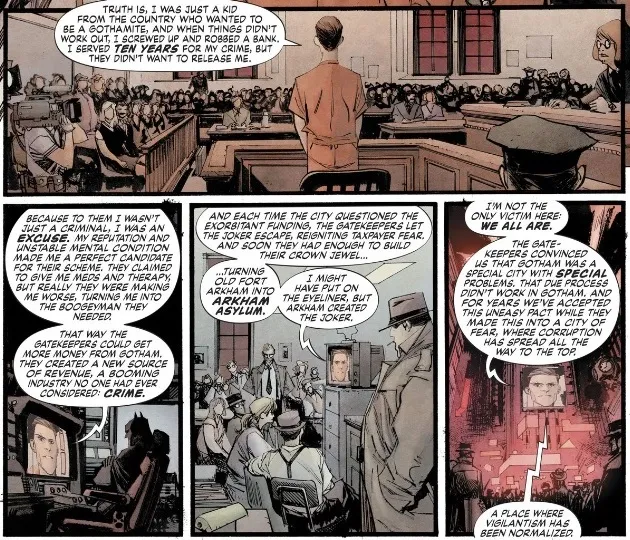

Batman: White Knight depicts an alternate universe in which the Joker is cured after Batman shoves a bunch of pills down his throat during a fight. Okay, that part probably isn’t realistic, but it does lead to some interesting discussions about whether or not the police department purposely turns mentally ill criminals into supervillains to justify their own violence and to enrich the wealthy, who rake in fortunes after each destructive battle between Batman and his adversaries. Batman’s refusal to acknowledge even the possibility that the Joker could be cured (and that he might have a point) has dire consequences.

Back in mainstream continuity, DC has taken the step of destroying Arkham Asylum in 2021’s Infinite Frontier #0. Rather than rebuild, they replaced it with Arkham Tower, the stated aim of which is to provide actual treatment to the inmates. (Things are already going wrong, but it’s a start.)

It’s easy to be skeptical about this, as comics have a tendency to revert to the status quo within a few years. Still, Infinite Frontier and Arkham Tower indicate a new willingness to at least consider new ways of depicting and treating those who either have or are presumed to have a mental illness.

Despite these promising changes, the depiction of mental illness in comics has historically been woefully inaccurate — like in Detective Comics #78, which seems to think a single fight is a good cure for PTSD — and in many ways continues to be so. Dr. Langley told me about a Two-Face story “in which the author identified the neurotransmitter as an antipsychotic.”

“That’s like calling gasoline a fire suppressant,” he added.

Dr. Langley and I discussed two possible reasons for these inaccuracies. The first — and the reason behind the neurotransmitter/antipsychotic comparison — is a basic lack of research. The second is that authors deliberately avoid depicting mental illness in a way that would enable audiences to make a specific diagnosis and thereby potentially malign those who live with that illness. Dr. Langley explained:

“When filming the movie Joker, Todd Phillips and his writers deliberately avoided depicting their Joker, Arthur Fleck, in a way that would neatly fit any real-world mental illness. They wanted to make certain they did not misrepresent any condition or cause people to think the worst of people who are truly mentally ill.”

I’m sure that Phillips and his team had the best of intentions, but for myself, I’m not sure these measures are enough. Even fantastical or deliberately vague portrayals of mental illness can be harmful.

Things to Keep in Mind

In the final chapter of Batman and Psychology, Langley relates several stories about Batman fans who were able to process trauma by watching Batman process his. Batman’s strength became theirs. The Dark Knight showed that, even if a traumatic event changes your life, it is within your power to make that change meaningful and positive. It’s impossible to overstate the power of storytelling — which is why any negative portrayal of mental illness should concern us.

You could correctly argue that people should not be getting their entire education on mental illness from a superhero. Realistically, however, the average person is far more likely to watch a Batman movie or play a Batman video game than pick up a psychology textbook. Langley’s books — which include not only Batman and Psychology but also The Joker Psychology and Daredevil Psychology, the latter of which he edited — might shrink that gap, but it won’t close it. Comic book creators need to realize this and act accordingly. The real-world consequences of not doing so can be truly upsetting.

One comics fan with OCD described how hurtful it was to see Spider-Man’s mentally ill friend Harry Osborn, who had previously been portrayed sympathetically and helped the fan to see that mental illness and evil do not go hand in hand, become a literal demon. Obviously, turning someone into a demon is not in any way an accurate depiction of mental illness. But it was still enough to hurt this fan.

Dr. Langley agreed that inaccurate portrayals of mental illness have the potential to do harm to mentally ill readers, and to readers who don’t know much about mental illness beyond what they see in the media. “Misrepresentation is always a risk and can be dangerous,” as he put it.

None of this is to say that comics should never depict a person with a mental illness in a bad or even villainous way. Like any other group of people, mentally ill people can be good, mean, kind, nasty, and everything in between. But given the profusion of negative stereotypes in comics and media generally, comics creators would do well to take a little more care when researching and discussing mental illness — and how they depict mentally ill characters.

As Book Riot’s Margaret Kingsbury wrote when discussing ableist tropes in literature, a good way to handle this issue is to include multiple disabled/mentally ill characters. This way, even if one isn’t the nicest person on the block, the others can “cancel out” any negative effect the villainous character might otherwise have on readers. So, even though Batman does not have a diagnosable condition, maybe he should.

At the very least, it’s time to stop acting like supervillainy is a natural, inevitable outcome of being mentally ill, or that mental illness is the driving force behind the villains in Batman’s — or anyone else’s — rogues gallery.