10 Things You Might Not Know About the Comics Code Authority

If you’ve looked into the history of the U.S. comics industry at all, you’ll have heard about the Comics Code Authority. The CCA was formed in 1954 by the Comics Magazine Association of America, sparked by an outcry over “immoral” content in reading material intended primarily for children. Essentially, the industry volunteered to self-regulate, submitting comics to the CCA for approval before publishing. If a comic didn’t carry the Comics Code seal, most newsstands wouldn’t carry it.

The Code steadily lost power from the late ’60s on, and by the 21st century, it was little more than decoration. In 2011, the last major publishers to bother getting the seal on their books, DC and Archie, broke with the CCA, rendering it functionally dead.

In honor of the ten year anniversary of this sad little fizzle that marked the end of an era, I rounded up ten interesting facts about the Comics Code Authority that you can impress your friends with at cocktail parties where the conversation revolves largely around comics history. Also, please invite me.

1. There were actual Senate hearings about comics.

Even as someone who loves comics, I feel like perhaps the highest legislative body in our country should probably have more pressing things to talk about, but apparently not! The increasing fervor over whether or not comics were Bad For Children led to the formation of the United States Senate Subcommittee on Juvenile Delinquency, which held hearings to discuss comic books in particular in spring of 1954. One of these was held on April 22, 1954 — the same day as Joseph McCarthy’s first hearing on supposed Communist infiltration of the Army, which is a neat little bit of timing if, say, you’re a 21st century writer looking to make a point about the culture of paranoia and repression that would lead to something like the Comics Code. Ahem.

2. Seduction of the Innocent wasn’t about whether Batman and Robin were gay.

One of the sparks that set off the anti-comics bonfire (and there were literal bonfires of comics in towns across America) was Seduction of the Innocent, the 1954 book by psychiatrist Fredric Wertham. Today, the book is probably best remembered for Wertham’s claim that Batman and Robin were lovers, which even at the time comics professionals found laughable (though Will Brooker’s Batman Unmasked argues that some of the early subtext was intentional and positive). Wertham also took issue with the widespread use of bondage in Wonder Woman comics (which was definitely supported by the text) and claimed she was a lesbian (dude, even in 2021 we can’t get DC to consistently admit that she’s bi).

But superheroes weren’t the most popular genre of comics at the time, and they weren’t Wertham’s main target. That was reserved for the often extremely gory and nihilistic crime comics that were dominating the market, particularly those by publishers like the now-defunct EC Comics.

3. Yeah, some of the comics really were pretty wild.

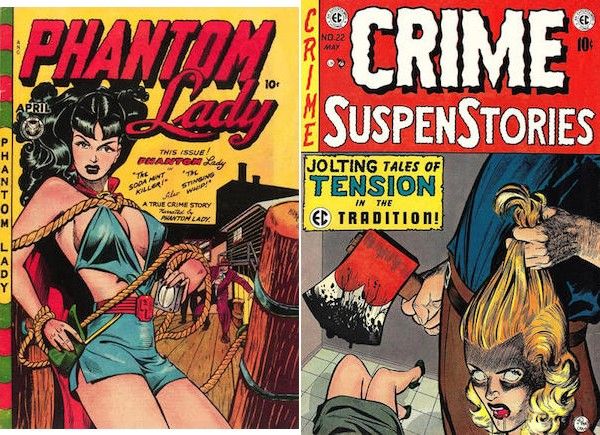

Today, most of us think of the early ’50s as a time of relatively tame, conservative media, thanks in no small part to the Hays Code, which did for movies what the Comics Code would do for comics. But the art could be pretty salacious — check out these covers to Phantom Lady #14 (Fox Comics) and Crime SuspenStories #22 (EC Comics).

EC publisher Bill Gaines testified during the hearings that his comics were limited by “the bounds of good taste,” which put him in the unenviable position of having to defend that second cover as “in good taste” when it was displayed in court. Bad taste, he explained through his visible flop sweat, would be if you could see blood coming out of the neck stump of either the head or the body. I feel for Gaines, a good dude who was pretty clearly targeted by the CCA in a way no other publisher was (in fact, the other publishers were fairly gleeful that the Code essentially ran his extremely successful company out of business), but every time I look at this ridiculous cover I laugh.

Bonus fun fact: Jack Kirby and Joe Simon watched the hearings on TV together and berated Gaines out loud at this embarrassing fumble.

4. The Code banned anything to do with horror.

Yeah, that thing about EC being drummed out of business? The Code specifically banned vampires, werewolves, ghouls, and zombies, as well as the words “Horror,” “Terror,” or “Weird” on covers. That…pretty much encompassed their entire line. Sorry, EC.

I’m not really sure how Harvey Comics, a vocal proponent of the Code, got away with Casper the Friendly Ghost (who debuted in 1952) and his various friends, which included a literal demon. (His name is Hot Stuff and he’s adorable.) I guess cuteness was a key factor? If only EC had tried to pitch Zachary, the Littlest Zombie!

5. As with most censorship efforts, the Code was hella racist.

One of the best known stories about the CCA has to do with an EC (of course) story called “Judgment Day,” in which a human astronaut visits a planet inhabited by robots to evaluate them for inclusion in the Galactic Republic, a sort of interstellar United Nations. When he realizes that the orange robots are bigots and oppressing the blue robots, he rejects their application. Returning to his spaceship, he removes his helmet to reveal that he is a Black man.

Comics Code Administrator Judge Charles Murphy informed EC that the astronaut could not be Black, for, you know…reasons. (The reasons were that he was racist.) Gaines got on the phone, cursed him out, and ran the story as it was. I told you he was a good dude!

6. Magazines were excluded from the Code, even though comics…are magazines.

Simply by changing the trim size, publishers could sell comics as “magazines” instead and thus avoid having to submit them for approval to the CCA. Gaines stayed afloat by dropping the horror and focusing on his humor book, Mad Magazine. It worked; even though he had to sell Mad in the ’60s, he stayed on as publisher until he died, and the magazine itself lasted until 2018.

Other publishers followed suit with some of their saucier material. Marvel’s The Deadly Hands of Kung Fu was a 1970s black and white magazine that combined reviews of kung fu films, martial arts instructions that you should almost certainly not attempt to follow, and comics featuring their martial arts–themed characters like Shang-Chi and Iron Fist. The comics were far more explicit than Marvel’s regular comics could be at the time; their Daughters of the Dragon stories alone included heroin use, sexual assault, and the aforementioned forbidden vampires (who were also heavily coded lesbians).

7. And speaking of drugs…

The Code didn’t specifically forbid the depiction of drugs initially, but it was generally assumed to fall under the rule about “good taste.” This prohibition was first tested in 1967, when Deadman’s first appearance in Strange Adventures #205 showed him fighting opium smugglers; the story passed the code without a problem.

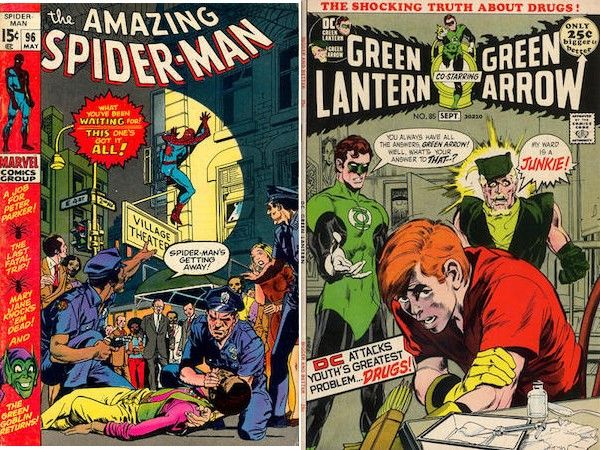

In 1971, the U.S. Department of Health, Education and Welfare asked Stan Lee for a story about drug abuse. He agreed and wrote The Amazing Spider-Man #96–98 (May–July 1971), in which Spider-Man’s friend Harry Osborn overdoses on pills. Since drugs were depicted as unequivocally bad and, you know, the government asked for the story, Lee expected it to be fine, but the CCA rejected it. Lee and his publisher Martin Goodman went ahead and ran it without the CCA Seal, to a positive reception.

Though DC head Carmine Infantino disapproved of Marvel’s “defying the code” (come on, dude), the code was quickly updated to permit the depiction of drugs as “a vicious habit.” Just a couple months later, Green Lantern/Green Arrow #85 (September 1971) famously depicted Green Arrow’s sidekick Speedy as a heroin addict in a story that won that year’s Shazam Award and a letter of commendation from then–NYC mayor John Lindsay. And it was Code-approved.

8. A spooky last name could be a victory for creator rights.

In the anthology book House of Secrets #83, a story written by Marv Wolfman was attributed in the narration to “a wandering wolfman,” which the CCA objected to. Well, asked Gerry Conway, what if the wolfman was a real dude and it was his actual name? The CCA agreed, on the condition that Wolfman receive an actual credit on the first page of the story for clarification, which set the precedent of DC crediting writers in this sort of anthology. The CCA…doing something good? Amazing!

9. The Code could make something seem worse than the original intention.

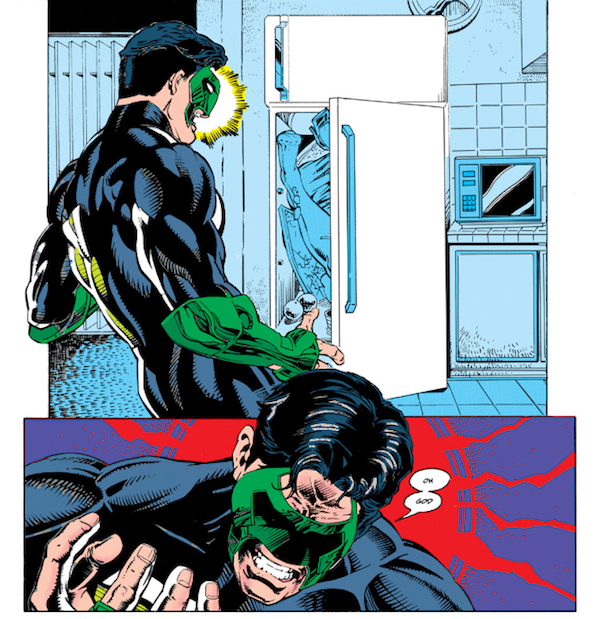

Green Lantern #54 (August 1994) is infamous for the scene in which the titular hero returns home to find that his girlfriend, Alex DeWitt, has been dismembered by a supervillain and stuffed in the refrigerator. The scene led Gail Simone to coin the term “women in refrigerators,” which has come to describe women killed or otherwise brutalized to further a male character’s narrative.

Except, writer Ron Marz has said, Alex was not dismembered. The original art showed her body intact in the fridge, but the CCA insisted that the door be drawn mostly closed, leading readers to imagine the gory sight Green Lantern was reacting to. “I think this actually says a great deal more about some readers’ minds than it does about our original intentions,” Marz said. I take his point, but dude still wrote a story about a woman being brutally murdered and stuffed in a fridge to teach Green Lantern a valuable lesson about…something. I can’t help but be reminded of Bill Gaines standing before a Congressional committee, trying to argue that a woman’s severed head was in good taste.

10. The CCA censored depictions of sex well into the ’90s, with…mixed results.

In Team Titans #8 (April 1993), Deathwing, an evil future version of Nightwing, sexually assaults Mirage, a member of the Titans. Or at least, that’s what any synopsis will tell you, but the art from the issue shows the two of them kissing, standing up and mostly clothed, before he attempts to stab her with a knife and then jumps out the window. In the next issue, Donna Troy asks Mirage if she thinks she should get tested for HIV, which had me flipping back and forth between the two issues, trying to figure out what I missed. I don’t know for certain that the CCA made DC change the content of the book, but I suspect either that or a proactive attempt to get around the CCA led to the weird disconnect between what the art depicts and what the characters later imply happened.

I’m not complaining that the art wasn’t more explicit — the last thing we need is more assault in comics — but the CCA’s blanket censorship also included safe sex and female pleasure. Devin Grayson once explained that she wasn’t permitted to show condoms on the nightstand during Nightwing and Huntress’s hookup in 2003’s Nightwing/Huntress one-shot. She also noted that the CCA wouldn’t let her have a female character say “That feels good” from behind a closed door in the 1999 Titans series. Because what would the children think, I guess?

The Code has been dead for ten years, but much like McCarthyism, this relic of 1950s anxieties is still with us in so many subtextual ways, like the overwhelming straightness and whiteness of the industry both on and off the page, and its love affair with authority. Let’s hope comics continue to change for the better now that the shackles are off.

If you want to learn more about why the Code came to be, I cannot recommend David Hajdu’s The Ten-Cent Plague: The Great Comic-Book Scare and How It Changed America highly enough. You can also read more about the history here, and the era of comics it created here.