Why I Started Reading Pakistani Feminist Poetry

This content contains affiliate links. When you buy through these links, we may earn an affiliate commission.

Owing to my cultural heritage, it’s a shame that I don’t know enough about Pakistani literature. As a child of immigrants who willfully chose not to embrace Urdu growing up, I regret my obstinance now. Plus, with the world suddenly closing off to each other physically in an effort gain control over COVID-19, keeping those cultural connections open and well-traveled seems more important than ever. My father has been trying to expose Urdu writing to me lately, in hopes that I will strive to learn the language through the artful direction of prose and poetry. And I am starting to, though probably not in the direction he was imagining. I am discovering the fiery female voices of Urdu poetry.

Pakistan has a long legacy of exquisite literature — in fact, the country bubbles with an abundance of women writers today, including Kamila Shamsie, Bina Shah, Sara Suleri, and Saba Imtiaz. But if we are speaking specifically of writing in Urdu, then you need to focus on poetry. Urdu exists for poetry — its cadence throbs like heartbeats, it rolls through the mouth and mind like cascading water. In short, it’s a beautiful language. Unfortunately I can’t read Urdu, but I can dig the translations for now. And as for the poetry itself, well, men dominate that scene — think of Faiz Ahmad Faiz, N.M. Rashed, Miraji, to name just a few. But it’s the women’s voices that have captured my attention and sing through my blood.

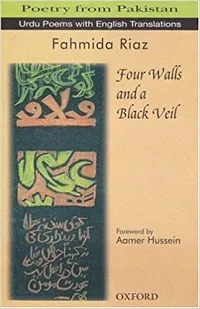

That fascination began with Fahmida Riaz (1946–2018), the first poet I started to read and whose fierce and seductive language struck my heart. Writer, poet, activist, feminist, she defied social norms with subjects matters that were altogether taboo for women to breathe and advocated for human rights until her death. And her words made me realize I had overlooked an entire world of Pakistani culture. How ignorant of me, how narrow-sighted.

Riaz’s poetry encapsulates the struggle that feminine perspectives face in being heard. A struggle that may take shape in many forms, but is essentially shared. Women’s voices often differ so obviously from men because of our subjugation and objectification, demanding us to speak of our blood and body entirely as our own. And this is common across the globe.

That fascination began with Fahmida Riaz (1946–2018), the first poet I started to read and whose fierce and seductive language struck my heart. Writer, poet, activist, feminist, she defied social norms with subjects matters that were altogether taboo for women to breathe and advocated for human rights until her death. And her words made me realize I had overlooked an entire world of Pakistani culture. How ignorant of me, how narrow-sighted.

Riaz’s poetry encapsulates the struggle that feminine perspectives face in being heard. A struggle that may take shape in many forms, but is essentially shared. Women’s voices often differ so obviously from men because of our subjugation and objectification, demanding us to speak of our blood and body entirely as our own. And this is common across the globe.

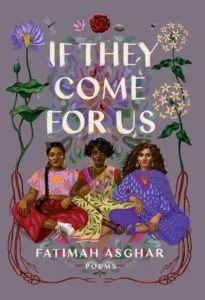

Since then, I have been delving into other writers, notably Kishwar Naheed (another revered, revolutionary poet) and Fatima Asghar, a contemporary young poet whose collection If They Come For Us (written in English) stokes flames that burn more closely to my life experiences and outlooks. These writers motivate me to actually take on learning Urdu itself, because I want to read the many authors in their true form, and let them cast their spell on me without any barrier. We’re constantly reminded that time is short, and living is only as long as we make it, so I’d like to live having a better connection to my sisters (and brothers) of my heritage.

Plus, I look forward to introducing some poets to my dad as well.

Since then, I have been delving into other writers, notably Kishwar Naheed (another revered, revolutionary poet) and Fatima Asghar, a contemporary young poet whose collection If They Come For Us (written in English) stokes flames that burn more closely to my life experiences and outlooks. These writers motivate me to actually take on learning Urdu itself, because I want to read the many authors in their true form, and let them cast their spell on me without any barrier. We’re constantly reminded that time is short, and living is only as long as we make it, so I’d like to live having a better connection to my sisters (and brothers) of my heritage.

Plus, I look forward to introducing some poets to my dad as well.

That fascination began with Fahmida Riaz (1946–2018), the first poet I started to read and whose fierce and seductive language struck my heart. Writer, poet, activist, feminist, she defied social norms with subjects matters that were altogether taboo for women to breathe and advocated for human rights until her death. And her words made me realize I had overlooked an entire world of Pakistani culture. How ignorant of me, how narrow-sighted.

Riaz’s poetry encapsulates the struggle that feminine perspectives face in being heard. A struggle that may take shape in many forms, but is essentially shared. Women’s voices often differ so obviously from men because of our subjugation and objectification, demanding us to speak of our blood and body entirely as our own. And this is common across the globe.

That fascination began with Fahmida Riaz (1946–2018), the first poet I started to read and whose fierce and seductive language struck my heart. Writer, poet, activist, feminist, she defied social norms with subjects matters that were altogether taboo for women to breathe and advocated for human rights until her death. And her words made me realize I had overlooked an entire world of Pakistani culture. How ignorant of me, how narrow-sighted.

Riaz’s poetry encapsulates the struggle that feminine perspectives face in being heard. A struggle that may take shape in many forms, but is essentially shared. Women’s voices often differ so obviously from men because of our subjugation and objectification, demanding us to speak of our blood and body entirely as our own. And this is common across the globe.

Since then, I have been delving into other writers, notably Kishwar Naheed (another revered, revolutionary poet) and Fatima Asghar, a contemporary young poet whose collection If They Come For Us (written in English) stokes flames that burn more closely to my life experiences and outlooks. These writers motivate me to actually take on learning Urdu itself, because I want to read the many authors in their true form, and let them cast their spell on me without any barrier. We’re constantly reminded that time is short, and living is only as long as we make it, so I’d like to live having a better connection to my sisters (and brothers) of my heritage.

Plus, I look forward to introducing some poets to my dad as well.

Since then, I have been delving into other writers, notably Kishwar Naheed (another revered, revolutionary poet) and Fatima Asghar, a contemporary young poet whose collection If They Come For Us (written in English) stokes flames that burn more closely to my life experiences and outlooks. These writers motivate me to actually take on learning Urdu itself, because I want to read the many authors in their true form, and let them cast their spell on me without any barrier. We’re constantly reminded that time is short, and living is only as long as we make it, so I’d like to live having a better connection to my sisters (and brothers) of my heritage.

Plus, I look forward to introducing some poets to my dad as well.