When Writing In Books Is Okay

This content contains affiliate links. When you buy through these links, we may earn an affiliate commission.

When I hear people talk about writing in books, my mind always goes back to an old library customer. We never managed to catch him doing it, but every time his books came back they had the word “liar” carefully written in alongside every mention of Tony Blair. Now, I admit that shows commitment, but it also breaches the first rule of writing in books: You don’t write in books that aren’t yours. Period. There’s nothing worse than finally getting that book you’ve longed for from the library and having to wade through somebody else’s copious highlights. (Sidebar: don’t ever, ever highlight a library book. Ever.)

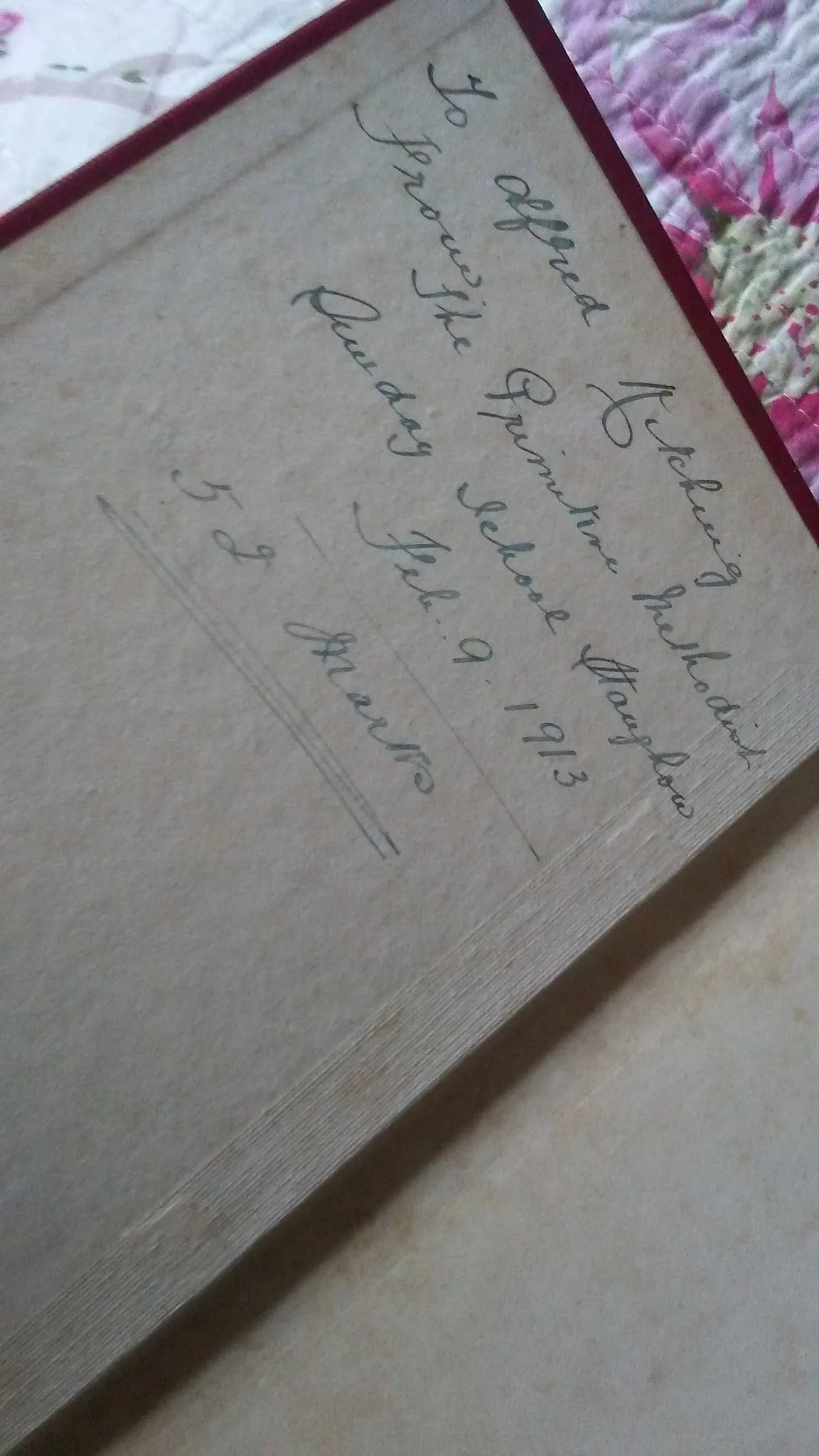

The rules of writing in books are, in fact, very simple. You can write in books you own, and you can write in books that you’re going to give to somebody. A handwritten dedication can be one of the most perfect things on earth and I love seeing them in the old books that I collect. It’s amazing how much emotion – both negative and positive – that people can get into a few words. Here’s one of my most recent favourites from ‘Brave Deeds For British Boys’ (c. 1913).

Dedications are snapshots of time and, when it comes to children’s books, a really useful guide to what adults thought was appropriate reading at the time. I can’t help but imagine Alfred’s face as he read this book where everybody Dies Nobly For The Empire (it’s not a great book). Did he like it? Did he even read it? I suspect he didn’t, as it’s in pretty good condition. I tried about ten pages and died of boredom. But without that dedication, I’d never have even known he existed, and now I do. Now we all do.

That’s what writing on books does: it makes you remember. The act of drawing that line beneath the words makes them burn into your mind. People. Places. Ideas. My copy of The Second Sex by Simone de Beauvoir is full of my notes. She made me do it. Every inch of that book is something I want to record and remember, and I don’t have the brain to do it unless I make a note. There and then. Just as I read it. I want to remember the way it made me feel.

Writing in books also bought us blackout poetry. There’s a point in almost every book’s life where it doesn’t to fit where it is, and it has to move on. Libraries get weeded (as they should), schools buy new editions, and people donate to charity shops. It’s the circle of literary life. But blackout poetry allows those books a chance to live again, and to tell a whole new story. What’s more, blackout poetry allows people to interact with language in a whole new way. Poetry can be intimidating. Reading can be terrifying. But telling somebody that they can make a poem out of something – and there’s nothing to stop them? That’s powerful. Books aren’t something we should be afraid of. We make them. We should be allowed to remake them.

You can write in your own books. You can draw in them. As far as I’m concerned, you could write a recipe for tomato soup or a shopping list in them. As long as they’re not one of the ten most expensive books on Etsy or something else that’s incredibly valuable, the world’s your oyster. Books aren’t something to be afraid of – they’re something to be a part of. Whether that’s writing in them, or making sculptures out of them, do it. Let these books tell another story. It’s fine by me.

To sum up: writing both in and on books is okay, as long as you’re not doing it in something that doesn’t belong to you. The world won’t stop turning and the books will survive. The stories will endure. Besides, if nobody had ever written on a book, we wouldn’t have grumpy medieval marginalia. I don’t know about you, but I want more “This parchment is hairy” in the world.

Dedications are snapshots of time and, when it comes to children’s books, a really useful guide to what adults thought was appropriate reading at the time. I can’t help but imagine Alfred’s face as he read this book where everybody Dies Nobly For The Empire (it’s not a great book). Did he like it? Did he even read it? I suspect he didn’t, as it’s in pretty good condition. I tried about ten pages and died of boredom. But without that dedication, I’d never have even known he existed, and now I do. Now we all do.

That’s what writing on books does: it makes you remember. The act of drawing that line beneath the words makes them burn into your mind. People. Places. Ideas. My copy of The Second Sex by Simone de Beauvoir is full of my notes. She made me do it. Every inch of that book is something I want to record and remember, and I don’t have the brain to do it unless I make a note. There and then. Just as I read it. I want to remember the way it made me feel.

Writing in books also bought us blackout poetry. There’s a point in almost every book’s life where it doesn’t to fit where it is, and it has to move on. Libraries get weeded (as they should), schools buy new editions, and people donate to charity shops. It’s the circle of literary life. But blackout poetry allows those books a chance to live again, and to tell a whole new story. What’s more, blackout poetry allows people to interact with language in a whole new way. Poetry can be intimidating. Reading can be terrifying. But telling somebody that they can make a poem out of something – and there’s nothing to stop them? That’s powerful. Books aren’t something we should be afraid of. We make them. We should be allowed to remake them.

You can write in your own books. You can draw in them. As far as I’m concerned, you could write a recipe for tomato soup or a shopping list in them. As long as they’re not one of the ten most expensive books on Etsy or something else that’s incredibly valuable, the world’s your oyster. Books aren’t something to be afraid of – they’re something to be a part of. Whether that’s writing in them, or making sculptures out of them, do it. Let these books tell another story. It’s fine by me.

To sum up: writing both in and on books is okay, as long as you’re not doing it in something that doesn’t belong to you. The world won’t stop turning and the books will survive. The stories will endure. Besides, if nobody had ever written on a book, we wouldn’t have grumpy medieval marginalia. I don’t know about you, but I want more “This parchment is hairy” in the world.

Dedications are snapshots of time and, when it comes to children’s books, a really useful guide to what adults thought was appropriate reading at the time. I can’t help but imagine Alfred’s face as he read this book where everybody Dies Nobly For The Empire (it’s not a great book). Did he like it? Did he even read it? I suspect he didn’t, as it’s in pretty good condition. I tried about ten pages and died of boredom. But without that dedication, I’d never have even known he existed, and now I do. Now we all do.

That’s what writing on books does: it makes you remember. The act of drawing that line beneath the words makes them burn into your mind. People. Places. Ideas. My copy of The Second Sex by Simone de Beauvoir is full of my notes. She made me do it. Every inch of that book is something I want to record and remember, and I don’t have the brain to do it unless I make a note. There and then. Just as I read it. I want to remember the way it made me feel.

Writing in books also bought us blackout poetry. There’s a point in almost every book’s life where it doesn’t to fit where it is, and it has to move on. Libraries get weeded (as they should), schools buy new editions, and people donate to charity shops. It’s the circle of literary life. But blackout poetry allows those books a chance to live again, and to tell a whole new story. What’s more, blackout poetry allows people to interact with language in a whole new way. Poetry can be intimidating. Reading can be terrifying. But telling somebody that they can make a poem out of something – and there’s nothing to stop them? That’s powerful. Books aren’t something we should be afraid of. We make them. We should be allowed to remake them.

You can write in your own books. You can draw in them. As far as I’m concerned, you could write a recipe for tomato soup or a shopping list in them. As long as they’re not one of the ten most expensive books on Etsy or something else that’s incredibly valuable, the world’s your oyster. Books aren’t something to be afraid of – they’re something to be a part of. Whether that’s writing in them, or making sculptures out of them, do it. Let these books tell another story. It’s fine by me.

To sum up: writing both in and on books is okay, as long as you’re not doing it in something that doesn’t belong to you. The world won’t stop turning and the books will survive. The stories will endure. Besides, if nobody had ever written on a book, we wouldn’t have grumpy medieval marginalia. I don’t know about you, but I want more “This parchment is hairy” in the world.

Dedications are snapshots of time and, when it comes to children’s books, a really useful guide to what adults thought was appropriate reading at the time. I can’t help but imagine Alfred’s face as he read this book where everybody Dies Nobly For The Empire (it’s not a great book). Did he like it? Did he even read it? I suspect he didn’t, as it’s in pretty good condition. I tried about ten pages and died of boredom. But without that dedication, I’d never have even known he existed, and now I do. Now we all do.

That’s what writing on books does: it makes you remember. The act of drawing that line beneath the words makes them burn into your mind. People. Places. Ideas. My copy of The Second Sex by Simone de Beauvoir is full of my notes. She made me do it. Every inch of that book is something I want to record and remember, and I don’t have the brain to do it unless I make a note. There and then. Just as I read it. I want to remember the way it made me feel.

Writing in books also bought us blackout poetry. There’s a point in almost every book’s life where it doesn’t to fit where it is, and it has to move on. Libraries get weeded (as they should), schools buy new editions, and people donate to charity shops. It’s the circle of literary life. But blackout poetry allows those books a chance to live again, and to tell a whole new story. What’s more, blackout poetry allows people to interact with language in a whole new way. Poetry can be intimidating. Reading can be terrifying. But telling somebody that they can make a poem out of something – and there’s nothing to stop them? That’s powerful. Books aren’t something we should be afraid of. We make them. We should be allowed to remake them.

You can write in your own books. You can draw in them. As far as I’m concerned, you could write a recipe for tomato soup or a shopping list in them. As long as they’re not one of the ten most expensive books on Etsy or something else that’s incredibly valuable, the world’s your oyster. Books aren’t something to be afraid of – they’re something to be a part of. Whether that’s writing in them, or making sculptures out of them, do it. Let these books tell another story. It’s fine by me.

To sum up: writing both in and on books is okay, as long as you’re not doing it in something that doesn’t belong to you. The world won’t stop turning and the books will survive. The stories will endure. Besides, if nobody had ever written on a book, we wouldn’t have grumpy medieval marginalia. I don’t know about you, but I want more “This parchment is hairy” in the world.