More Important Offices than Merely to Keep Us Warm: The Relationship Between Fashion and Literature

Fashion and literature have a long, intricate relationship. Authors have long been aware of this: the ever clear-sighted Virginia Woolf always paid attention to her characters’ sartorial choices: Mrs. Dalloway’s green dress is considered almost as its own character. But in her 1928 novel Orlando, it became clear that Woolf’s attention to clothing in her books was very much a conscious choice: “Vain trifles as they seem, clothes have, they say, more important offices than merely to keep us warm.”

Woolf was correct, as usual. Our clothing can speak to who we are, who we want to be, and how we want to be perceived by the world. Indeed, Woolf is not the only writer to pay attention to attire: on the contrary, authors have been building character through their fashion choices since the dawn of literature. Take the heroine of L.M. Montgomery’s The Blue Castle for instance, Valancy Stirling, starts out as a timid and browbeaten woman with one brown dress. As she frees herself from the constraints of her family and her life, she purchases a sleeveless green gown. Then a red cape. By the time the novel ends, there is as much color in Valancy’s wardrobe as there is in her new life.

It is clear, then, that fashion has always influenced literature. But what about the other way around? Literature has certainly influenced readers’ sartorial choices: in her article “Off the page: fashion in literature,” Helen Gordon recounts the many ways in which her personal style was influenced by books throughout her life. I’ve written previously about how much books have influenced my choices and outlook throughout the years, and my clothing choices are not an exception. It would seem I’m not alone, as academia is full of analysis about literary characters’ styles. Then there are the myriad online groups and Pinterest boards by readers finding clothing inspiration in books.

Sometimes, this inspiration takes on a particularly significant form, like when fashion designers build entire collections around specific books. Such is the case for the aforementioned Orlando: several fashion houses used it as inspiration for their shows and/or lines. Among these can be counted Christopher Bailey’s AW16 Burberry show and Ann Demeulemeester’s AW07 collection. Alexander McQueen, on his part, took inspiration from Stephen King’s The Shining for his AW99 show “The Outlook.”

Over the last decade, however, celebrities and influencers have exercised their influence in a different way. From performers who have hosted online book clubs (such as Emma Watson, Reese Witherspoon, and Kaia Gerber) to celebrities who share books they have read on social media, sometimes a mention or photograph is enough to propel a book into the field of public awareness. They sometimes even take it a step further, as is the case with book stylists.

It was not until I started reading about the connection between fashion and literature that I found out about the existence of a book stylist, and I don’t mean the kind who selects books for home décor. According to Nick Haramis, “rumor had it that celebrities and fashion influencers were paying someone to select reading material for them to carry in public.” I don’t know whether that’s true or not; I’m rather inclined to think not (look, I can buy that somebody will carry a book to look smarter. But to pay somebody else to choose it for them? Just run a basic Google search and save that money).

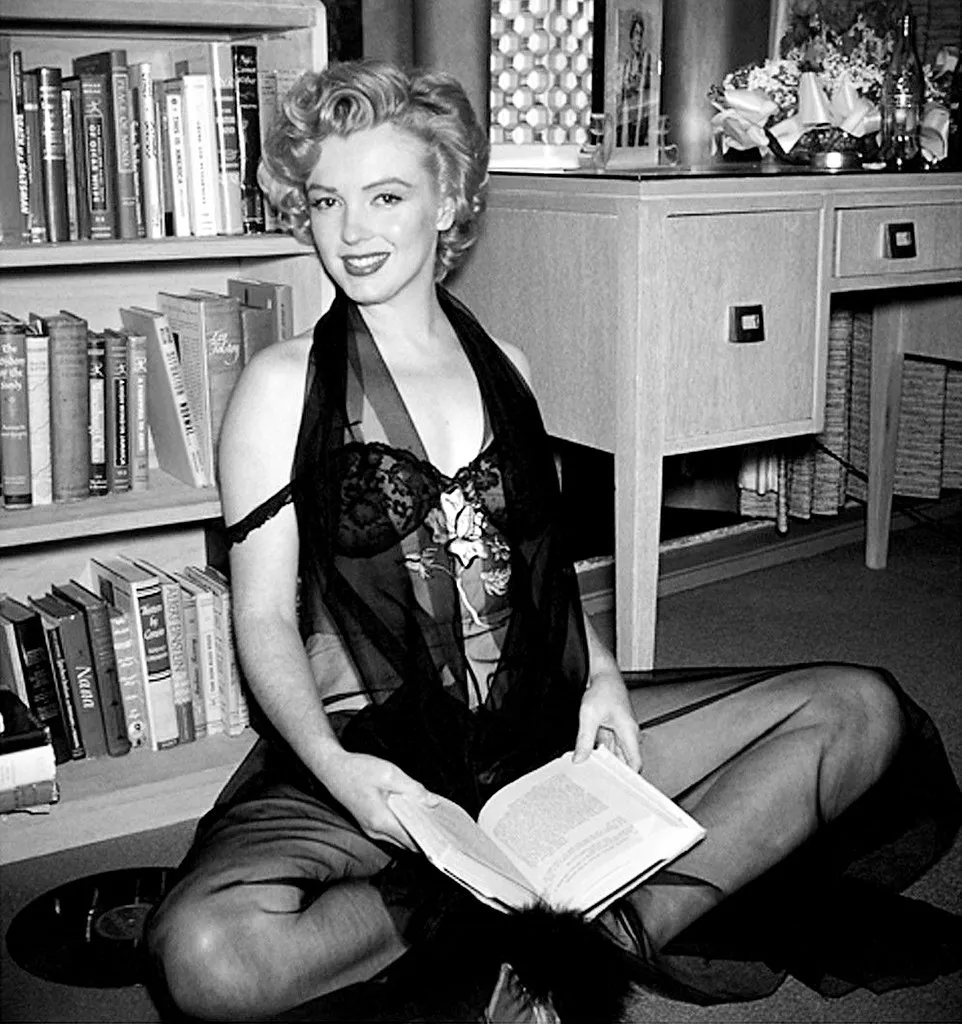

The rumor itself, regardless of its truth or lack thereof, brings to mind an unfortunate reality: fashion is perceived by many as unimportant and shallow, whereas literature is perceived as intellectual and even snobbish at times. This is stereotyping at its finest — or rather, at its worst. Take Marilyn Monroe’s ill-fated marriage to Arthur Miller, for instance. The press, not to mention the public, were baffled. A magazine dubbed it “the most unlikely marriage since the Owl and the Pussycat,” in reference to Edward Lear’s 1871 poem. Their preconception of Monroe as an empty-headed sex symbol, and of Miller as somebody who was too smart, and perhaps too boring for her was set in stone.

This hasn’t really changed. Every time a picture of a famous woman reading a book emerges, they are automatically presumed of doing it for the cameras. This is especially true if the woman in question is a model or somebody whose looks play any part in her work, and even more so if the book is a classic or otherwise considered “difficult” or “serious.” As long as this prejudice is rampant, the close relationship between fashion and literature will continue to be underestimated and misunderstood.