The Flash, Pandemic Burnout, and Me

Like pretty much, oh, everyone in the entire world, the past few years have been pretty rough for me. Between a worldwide pandemic, an increasingly alarming political landscape, and personal crises, I’ve struggled to balance my day job, my outside responsibilities, my creative projects, my relationships, and necessary self-care. Most days, I feel like I’m dropping several balls.

Lately, I’ve found myself returning to a comic published 34 years ago that has nothing to do with any of that. It’s Secret Origins Annual #2 (September 1988) — specifically, the lead story, “The Unforgiving Minute,” by William Messner-Loebs and Mike Collins.

Messner-Loebs’s run on the Flash is probably the most underrated in the character’s history. It’s overshadowed by the spectacular Mark Waid run which followed it, but Waid was building on the tremendous work Messner-Loebs had done before him, which included introducing Linda Park, the love of Wally West’s life, and establishing the reformed former supervillain Pied Piper as gay — only the second recurring DC character to come out, and the first man. At the time of this annual, Messner-Loebs had only been writing The Flash for a month, but this issue is a solid preview of the impressive run to come.

In 1988, Wally West was not in a great place. Two years prior, his beloved uncle Barry Allen, the second Flash, had died in Crisis on Infinite Earths. Wally, the former Kid Flash, had decided to come out of retirement and honor his uncle by becoming the new Flash. Not only was he a reluctant hero wrestling with an enormous amount of responsibility and grief at a very young age (he’s maybe 20 at this point), he was also struggling with his speed, which was greatly reduced from the over-the-top heights of the Silver Age. As a child, he could run faster than light; in 1988, he was lucky to approach the speed of sound.

And so he goes to therapy. Dr. Slade was a semi-recurring character in the Messner-Loebs run, usually used more as a prop for exposition and comic relief than anything else. He’s kind of a sleazebag and not a very good therapist, but he’s actually helpful in this issue — and not just to Wally.

Secret Origins was, as the name implied, a book for detailing the origins of various characters, and so Wally helpfully exposits his history: his childhood, how he got his powers, the Flashes that came before him. And sprinkled throughout, the rules Barry imparted when Wally was only ten, which Dr. Slade sums up as: “‘Never use your powers for yourself. Always serve others. Be brave. Be strong. Never take yourself too seriously…’ Pretty hard to live up to.”

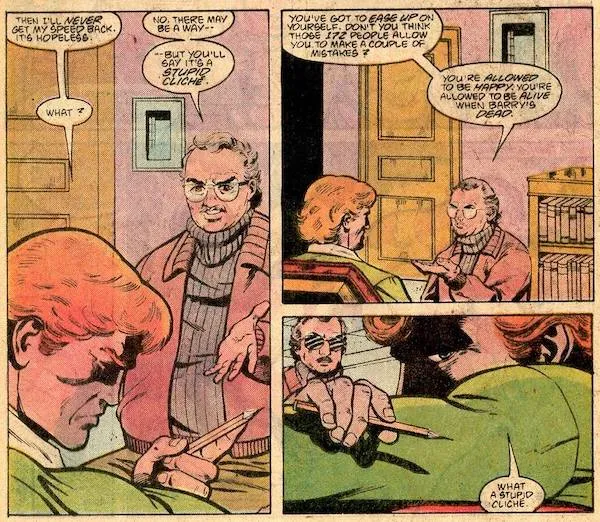

As Wally’s unexamined self-loathing and impossible standards pile up, Dr. Slade comments that Barry sounds like “a real hard-nose,” much to Wally’s angry denial. He asks Wally to tally up all the lives he’s saved as a superhero — not in big universe-saving events, just pushing people out of the way of cars and stuff. Wally can “only” come up with 172. “Barry set an example,” he says. “I’ve got to live up to it.”

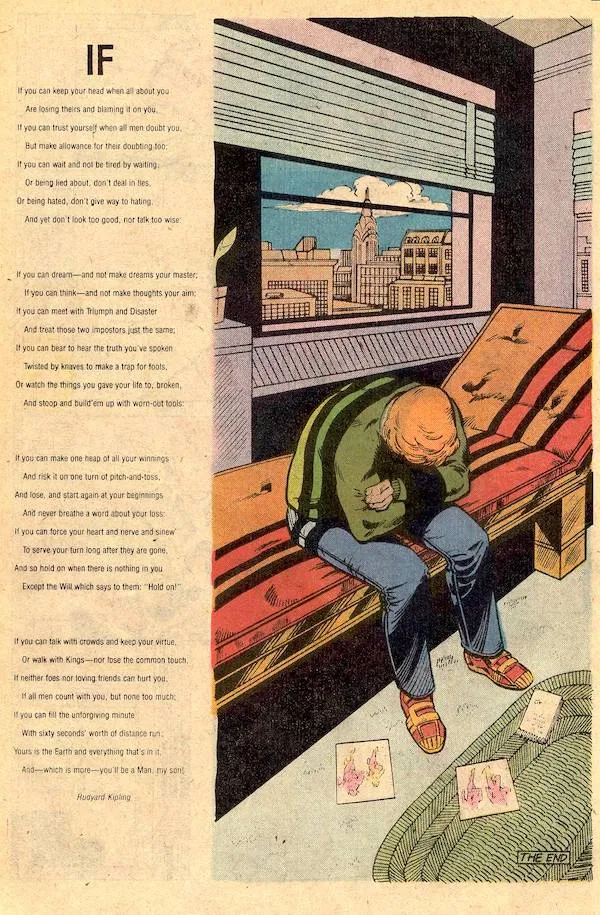

Then Dr. Slade quotes Rudyard Kipling: “If you can fill the unforgiving minute, with 60 seconds’ worth of distance run…”

It’s from Kipling’s poem “If—,” which Dr. Slade describes as “a recipe for being successful, moral, and a man.” The New Statesman says it “sums up the British cult of stoicism, the stiff-upper-lip.” It exhorts readers to do things like “Meet with Triumph and Disaster/ And treat those two imposters just the same” and “hold on when there is nothing in you.”

Wally recognizes the poem. Barry had it framed on his wall. Because of course he did.

Dr. Slade then tells Wally about imposter syndrome, which surprised me since I didn’t realize the concept had been around in the ’80s. (It turns out it’s been around since the ’70s, and though Dr. Slade claims that “classically, it’s what boys feel who lose impressive father figures,” it was introduced in the article “The Impostor Phenomenon in High Achieving Women” by Pauline R. Clance and Suzanne A. Imes. But superhero comics will be superhero comics, I guess.)

“I don’t need to know this junk!” Wally says. “I just want to run faster!”

“There may be a way, but you’ll say it’s just a stupid cliche,” Dr. Slade replies. “You’ve got to ease up on yourself…You’re allowed to be alive when Barry’s dead.”

“What a stupid cliche,” Wally says.

The appointment ends. Dr. Slade leaves the office, and Wally is left staring at pictures of himself and Barry, and his tally of the 172 lives he’s saved, with the full text of “If—,” in all its uncompromising insistence, laid out next to him.

I’ve read this story several times over the years, and it’s always resonated with me. In fact, it resonated with me so much that once, a few years back when I was really into bullet journaling, I put that quote from “If—” on a weekly spread as a means of inspiring myself to greater productivity. Yes, I am aware that this was in fact completely missing the point.

The last time I read the story, I cried.

I have not saved 172 lives, and I have not inherited the mantle of a beloved uncle after he saved the universe by destroying an anti-matter cannon by running until he died from it. I am just an ordinary human being.

But that’s why superhero comics work, isn’t it? They take the ordinary and they blow it up into cosmic proportions, turning everyday trials and tribulations into larger-than-life metaphors. I might not be the Flash, but I did get so caught up in holding myself to impossible, exhausting standards that I thought Rudyard Kipling was a good source for an inspirational quote. I mean, come on.

I’m sorry to say that this comic didn’t fix me. I’m self-aware enough to know that I’m still right there with Wally, grumbling “What a stupid cliche” at my therapist because I’m not ready to accept that I can’t stuff 60 seconds’ worth of distance run into that unforgiving minute — or maybe even 70 or 80, if I really try.

But when I catch myself doing that, I try to remember that the Victorians were terrible role models and Barry Allen literally ran himself to death. And it’s worth noting that the New Statesman article I quoted before is about how “If—” has become even less tenable of a goal during the still-ongoing pandemic, and suggests another point of inspiration instead: “Still I Rise” by Maya Angelou.

Thirty-four years after the publication of “The Unforgiving Minute,” Wally’s still a work in progress, and so am I. But I think replacing “If—” with “Still I Rise” is a pretty good place to start.

One final note: William Messner-Loebs, who has given comics so much, was until recently living in transient housing with his wife. Earlier this year they moved into assisted living with the help of Hero Initiative, a non-profit dedicated to helping comic creators in need. I guarantee you that if you have enjoyed a piece of superhero media…basically ever, you owe part of that enjoyment to someone who was helped by Hero Initiative, and I highly recommend donating if you can.