The Superficiality of Villainy

Everyone loves a good villain. One who cackles at the sky and shakes their fist and brings some form of doom to something or someone. It is fun to have someone to root against and root for — especially if they have a fun, cosplay-worthy aesthetic. With all that goes into stanning our favorite villains of all time, there is something to be said about examining the superficiality of villainy.

Like many character types, villains have often been visually identifiable. They have some costume or way of moving or physical features that mark them as villains in the story. Villains look bad or evil. Villains just look like villains. This is where some of the problems start with who we assign villainy to in storytelling. A hero versus villain narrative is often an Us versus Them set up, with Us being on the side of the hero and Them being on the side of the villain.

I recognize that sympathetic villains have recently been on the rise. I, for one, have also argued there are more generous ways of interpreting villains from our literary past. Nevertheless, when we look at the big picture of villains, they are often the othered members of society who are wrong or bad or shunned.

My short article is not going to provide all the necessary insights into decades of antisemitic, racist, homophobic, and/or ablest villain imagery. This is many people’s entire life’s work. I will break down some elements of the superficiality of villainy as a way of beginning to look at past depictions of villains to develop an understanding of how to move forward.

Medieval Origins of the Superficiality of Villainy

As a medieval and early modern lit girl, my understanding of villainy and monstrosity does come from an older European perspective. Bear with me. In Figuring Racism in Medieval Christianity, M. Lindsay Kaplan lays out how medieval Christianity created ideas of racist religious identities for non-Christian people as a way of establishing a superior/inferior relationship. In a perhaps oversimplified sentence, it’s the idea that religious racial inferiority was created to establish Christian superiority in medieval European society. These antisemitic ideas developed into some supernatural ways of othering Jewish people in society.

Antisemitism and the Villain

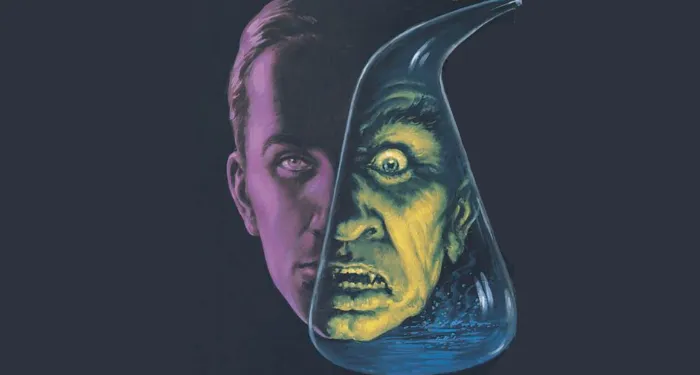

This is where one antisemitic visual aspect superficiality of villainy really comes into play and makes sense. In the medieval period, there was an idea that Jewish religion should be visible. Part of these antisemitic ideas has sunk into monsters and villains that are still around today. I would highly recommend reading Jeffrey Jerome Cohen’s work on medieval monsters in Monster Theory: Reading Culture for more insight into the subject.

One example of an antisemitic visual cue for villainy is the hooked nose. Adding a large or hooked nose only to an evil character is a visual indication to the audience that there is something wrong and abnormal about the character. The nose is an unavoidable visual cue at the center of the face that is unchangeable. In the context of bad witches in fantasy or evil scientists in science fiction, it can also be a sign of inherent evil. It comes from medieval European antisemitic imagery.

Another example of superficial villain imagery with medieval origins is the use of blood magic by only the story’s villain. The Christian accusation of blood libel is the false belief that Jewish people use Christian blood for ritual purposes. When a fantasy story establishes good characters using non-blood magic and evil characters using blood magic, it repeats the antisemitic shorthand. More importantly, when blood magic is the thing that differentiates bad characters from good characters, it is impossible to avoid perpetuating historic antisemitic hierarchies.

The Superficiality of Villainy and Darkness

Science fiction and fantasy readers also have to reckon with an understanding that the light versus dark divide in characters is linked to racist ideologies. A great place to start is with Things of Darkness by Kim F. Hall. She looks at the development of the association of darkness with evil in renaissance England. Darkness and otherness became linked in a way that many fantasy authors find difficult to unlink.

It certainly doesn’t help that fantasy writers in the 1900s perpetuated the links between dark as bad and white as good in their novels. When discussing J.R.R. Tolkien’s work, many scholars have spent time unpacking the racist elements of his worldbuilding. As Helen Young points out in Race and Popular Fantasy Literature: Habits of Whiteness, many fantasy worlds were inspired by a white male Eurocentric viewpoint. It has become a habit to associate lightness with heroism and darkness with villainy and it is close to impossible to shake.

Villains and Ableism

Then you have all the ableist depictions of villains. One great article broke down the ways to identify ableist patterns in monsters as a way of working against the many ableist visual cues. Villains can have low intelligence, sensory disabilities, and facial differences that classify them as different from the heroes.

In science fiction and fantasy, the creation of beautiful intelligent heroes and ugly unintelligent villains is a way of repeating ableism in imagined worlds. Badness or villainy is not just an interior state or a set of bad choices but something that is inherent, genetic, or outwardly visible. It just became another way of rationalizing ableism in society and reinforcing otherness.

The Queer-Coded Villain

Homophobia and the superficiality of villainy does not fare much better. While I could point to many potential origins of queer coding villains, for the United States at least, the enforcement of the Hays Code in 1934 is certainly a place to start. The code only allowed filmmakers to show queer characters if they were clearly negative characters. Because villains were clearly negative and the ones receiving punishment in stories, they could be queer-coded. While the code applied to film and TV, the queer-coded villain also appeared in literature.

That is to say, there are a lot of factors that contribute to why villains so often carry a specific ableist, racist, and/or homophobic aesthetic. Quite frankly, most of it reinforces real-life hierarchies. Old villain visuals tell audiences “These people are inherently bad and they deserve punishment because they are clearly irredeemable.” It is important, I think, that authors have done a lot to change perceptions of monstrous or villainous characters in modern fantasy.

Rethinking What Our Heroes and Villains Look Like

Adult Fantasy and Supporting Villains

The Jasmine Throne by Tasha Suri highlights monstrous female characters who are excellent at what they do. Sure, what they do is dismantle misogynistic, colonial empires, with a combination of political manipulation and ancient magic, but they really do it with style. Suri centers sapphic Desi women in a South Asia–inspired fantasy world that is told from the perspectives of people who could be considered villainous in other circumstances. She certainly is part of the rise of “we support women’s wrongs” and unlikable women in literature.

YA Sci-Fi’s Rehabilitation of the Villain

The sympathetic villain trend in science fiction and fantasy flips the idea that the heroes in the story are good people. Iron Widow by Xiran Jay Zhao is a YA science fiction book that features another monstrous female character highlighted for her excellence at a job people think she shouldn’t be able to do. Her lead characters are actively punished by their government for their abnormal strength and nonconformity. In this case, the others in society, or the proposed villains are positive forces of change.

Henches and Supervillains in Adult Sci-Fi

Writers have changed the superhero versus supervillain dynamics in stories as a way of disassociating old visual cues that defined the superficiality of villainy. Hench by Natalie Zina Walschots is a workplace fantasy novel where the villain’s hench workers are people just doing a job. In this world, superheroes are not all so good. In this case, the scariest character in the novel has governments and advertisers clamoring to support him because they have dubbed him a hero. When you look at the story, the real villain isn’t the cane user or the non-humanoid villain, but the smiling man who is there to save the day.

Fantasy Romance’s Love of Villains

I would be doing us all a great disservice if I did not recognize the way fantasy romances dismantle negative villain stereotypes. That Time I Got Drunk and Saved A Demon by Kimberly Lemming flips the idea of good and evil fantasy species. Here, the god is the real villain, and the old villains are on a quest to save enslaved demons. Falling in love with stereotypically evil fantasy creatures is a really great way of breaking down harmful visual cues in the fantasy genre as a whole.

What to do with the superficiality of villainy?

Again, this isn’t a comprehensive outline of all the ways the superficiality of villainy comes with ableist, racist, and/or homophobic visual cues. I also haven’t talked about all the new books that don’t buy into old stereotypes in science fiction and fantasy. It is just a place to start.

I think by breaking down the relationship between old visual cues that construct the superficiality of villainy, we can help get rid of some of the ableist, racist, and/or homophobic elements in science fiction and fantasy. Instead of reproducing harmful villain stereotypes, these books redefine evil. We need to ask ourselves: “Who do we want our villains to be?” and follow it up with “Why them?”

It takes the hard work of science fiction and fantasy authors, editors, and readers who understand the potential harm that can come in the form of traditional villains and monsters. Paying sensitivity readers also helps, but the more work everyone interested in science fiction and fantasy does to be aware of harmful stereotypes the better. If you miss something, apologizing, learning, and doing better the next time can do a world of good. We’re not perfect. But if we want to change the ways the superficiality of villainy has harmed people in the past, we have to do the heroic thing. We have to try.