7(ish) of the Most Controversial Comics of All Time

Comic books are ripe for controversy. They’ve historically been aimed primarily at children, which leaves them primed for “think of the children!” pearl-clutching, even though comics for adults have existed for decades. They’re easy to take out of context by grabbing a panel or two and sending them hurtling around the internet. And, in the case of superhero comics at least, they tend to star decades-old, iconic, beloved characters whose fans do not take kindly to change. Or character death. Or heel turns. Or radioactive…uh, we’ll get to that one.

As a lover of comics history and also of fandom drama, I’ve rounded up some of the most controversial comics of all time for your reading pleasure.

But before I jump into this list, I want to note a specific kind of controversy: book bans and challenges. Comics often top lists of the most frequently banned and challenged books, and just like with prose books, book banners target comics by BIPOC and LGBTQ+ creators in an effort to silence those voices. This is a way more serious issue than “fans didn’t like this Spider-Man storyline” and something we should all be pushing back against. To see some of the most challenged comics in America, click here, here, and here; to learn more about how to fight book bans, click here.

Now, on to the (sometimes) sillier controversies!

EC Comics and the Comics Code Authority

Banning comics isn’t anything new. In the years after World War II, comics experienced a backlash from parents and other authority figures who thought comics led to juvenile delinquency. This culminated in 1954 with Senate hearings (yes, the real Senate) to debate the impact of comics on children.

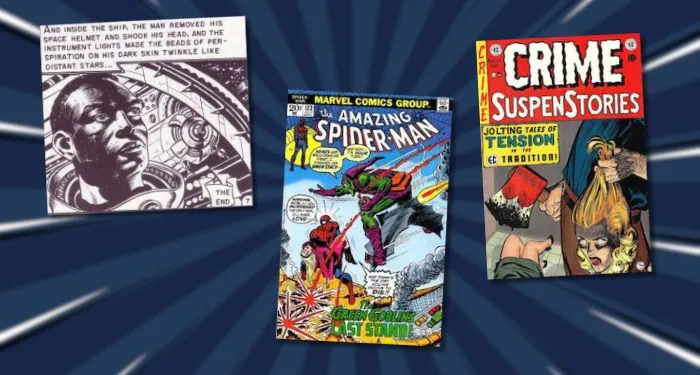

One of the people who testified was Bill Gaines, publisher of EC Comics, which specialized in the crime and horror comics that parents found particularly objectionable. After Gaines stated that he only published comics that were “in good taste,” a senator held up Crime SuspenStories #22 (April-May 1954), which showed a woman’s severed head being held up by the hair, and asked if it was in good taste. Poor Gaines had to argue that it was. It was not a convincing argument.

These disastrous hearings led to the formation of the Comics Code Authority, a censorship board which banned “objectionable” content in comics…including horror, which torpedoed the once-successful EC Comics. Poor Bill Gaines.

Judgment Day

EC didn’t die immediately. Most notably, they moved into humor by creating MAD Magazine. They also pivoted to sci-fi, and in Incredible Science Fiction #33 (February 1956), they published a story called “Judgment Day,” by Al Feldstein and Joe Orlando.

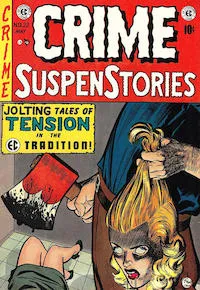

In the story, a human astronaut, his face hidden by his helmet, goes to a planet inhabited by blue and orange robots to determine if the planet should be permitted to join the Galactic Republic. Upon discovering that the orange robots oppress the blue robots, the astronaut tells them they can’t join the Republic until their bigotry is addressed. He then returns to his spaceship and removes his helmet to reveal that he is Black—a groundbreakingly progressive twist in 1956.

The Comics Code Authority objected, saying that the astronaut couldn’t be Black. Our old friend Bill Gaines called them, shouting that that was the entire point of the story, that they had not violated the Code in any way, and that he would sue. The CCA said fine, the astronaut could be Black, but not sweaty. “Fuck you,” said Gaines, and hung up.

The comic was published with the art unchanged, and the Comics Code Authority seal on the cover. Good job, Gaines!

The Night Gwen Stacy Died

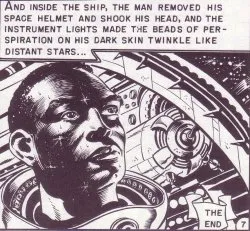

In Amazing Spider-Man #121 (June 1973), by Gerry Conway and Gil Kane, the Green Goblin kidnaps Spider-Man’s girlfriend, Gwen Stacy, and throws her off the top of the George Washington Bridge. Spider-Man catches her with some hastily flung webbing, but the impact snaps her neck, killing her.

Character deaths are a dime a dozen in comics these days, and for a few decades there, heroes’ girlfriends were particularly vulnerable to grim fates, so much so that comics writer Gail Simone coined the term “Women in Refrigerators” (after Green Lantern’s girlfriend was killed and stuffed in a fridge) and its derivative, fridging. But in 1973, Gwen’s death signaled a sea change, so much so that some historians consider this issue the end of the innocent Silver Age and the beginning of the angstier Bronze Age.

Certainly, it was a complete shock to readers, who were so furious that Conway claims he avoided comics conventions for a decade afterward. But even more interesting to me is the fact that the controversy was in part coming from inside the house. Stan Lee, who was Marvel’s publisher at the time, would claim that he’d had no idea it was going to happen and hated it. Roy Thomas, who edited the book, claimed that Stan had signed off on it. Over the decades, everyone involved has told multiple contradictory stories about whose idea it was and who was or wasn’t always against it.

And then there’s the question of who actually killed Gwen. Was it the Green Goblin, who threw her off the bridge? Or Peter, by accidentally snapping her neck? The Green Goblin states that the fall killed Gwen before the webbing reached her, which makes no sense, but has added its own level of confusion. Marvel in those days employed “the Marvel Method,” in which the artist drew the comic before the writer wrote the dialogue and sound effects, so did Gil Kane put blood on Peter’s hands when he drew Gwen’s neck at that angle, or did Conway do it when he wrote the “Snap!”?

Thousands upon thousands of words have already been written about this question, and I’m not going to solve any of it here. But as a New Yorker, I want to highlight yet one more controversial aspect of this comic: why does the script say this took place on the George Washington Bridge when the art could not more clearly show the Brooklyn Bridge? Conway and Kane, you have much to answer for.

Emerald Twilight and H.E.A.T.

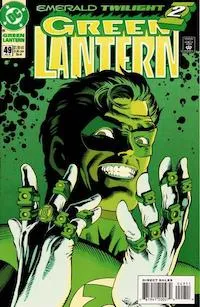

In 1994, Coast City, the hometown of Green Lantern Hal Jordan, was destroyed by a supervillain. Devastated, Hal became the villain Parallax, killing a number of fellow Green Lanterns as well as his alien bosses, the Guardians, in order to take their power and restore Coast City. He eventually tried to remake the entire universe, but was stopped by basically every DC hero, including the new Green Lantern, random dude Kyle Rayner. Kyle got a new comic and a spot on the Justice League; Hal slunk off in defeat.

Hoo boy, did Hal fans not like this. A number of them formed H.E.A.T., Hal’s Emerald Attack Team—later renamed to Hal’s Emerald Advance Team because, uh, announcing you’re going to attack people on behalf of a fictional character looks bad. They flooded DC with letters demanding the restoration of Hal as THE Green Lantern and for the writer of the (editorially mandated) “Emerald Twilight” story to be fired, spammed message boards (this was the ’90s, remember), and even ran ads in support of their campaign.

It didn’t really go anywhere. Kyle was a popular character who held down the Green Lantern title for a decade before publishing trends shifted and the decision was made to bring back Hal as a hero. The bad blood between Hal and Kyle fans is mostly cooled now, even if some Kyle fans (me) would like to see him get top billing a little more often. But the H.E.A.T. website, hilariously hosted on Tripod, is still up, and you can apparently still email them at their AOL email address and pay $5 for a laminated membership card. Also, if you tweet about them, you will get Um Actuallyed about how they were really a charitable organization and not a harassment movement. Ask me how I know.

Spider-Man’s…Just Everything, Honestly

Poor Peter Parker. Not only is he constantly kicked around in-universe, he’s been at the heart of so many controversial storylines that I had to combine just a few of them into one entry rather than make this an all-Spidey list.

For starters, there was the infamous Clone Saga that ran from 1994 to 1996. This was an attempt to mimic the sales of major “event” comics like the Death of Superman via shock value (and also get rid of Spider-Man’s marriage) by bringing back a clone of Spider-Man from the ’70s, then revealing that the clone was the real Spider-Man, and the Peter readers had been following for two decades had been a clone all along. This was obviously widely hated, and continual attempts to extend and complicate the story to chase sales, plus battles between writers and editorial, left the comics themselves confusing and riddled with plot holes.

Then there was 2003’s Trouble, a teen drama that revealed that Spider-Man’s beloved Aunt May had cheated on Uncle Ben with his brother Richard, gotten pregnant, and given the baby to Richard and his girlfriend Mary, making Aunt May Peter’s biological mother. This was meant to launch a new romance imprint for Marvel but it, uh. Failed.

The sexual shenanigans continued in 2006’s Spider-Man: Reign, set 30 years in the future. Not only was it revealed that Mary Jane had died of cancer contracted from exposure to, um, Peter’s radioactive semen—yes, really—but issue #1 included a drawing of a nude, elderly Peter Parker in which his genitals were (just barely) visible. The issue was recalled, and the panel was altered in later printings. (Some may recall a similar fate happening to an admittedly much more virile Bruce Wayne in 2018’s Batman: Damned.)

And then, of course, there was 2007’s “Spider-Man: One More Day,” in which Peter traded his marriage to Mary Jane to the devil to save Aunt May’s life. Funnily enough, this was motivated by the same thing the Clone Saga was: Marvel writers and editors hated that Peter was happily married. This may be the most loathed of the Spider-Man examples I have here—at least, it’s the one fans are still actively angry about since its effects are still ongoing—although that didn’t stop the movies from taking inspiration from it. (The newspaper strip also ran a similar plotline, although the backlash was so severe that Stan Lee, who was writing the strip at the time, ultimately revealed that it was all a dream, which is hilarious.)

These are just some of the Spider-controversies that have occurred over the years—I haven’t even mentioned Spider-Woman’s butt—and they all seem to center on wretched attitudes towards the women in Peter’s life. Patriarchy really does hurt (Spider-)men, too.

Holy Terror

There are few comic book creators more controversial than Frank Miller. While many of his comics from the ’80s, particularly Batman: Year One and The Dark Knight Returns, were groundbreaking at the time and are still considered classics today, they’ve also been criticized for racism, sexism, and homophobia. These themes only became more pronounced—and more critiqued—as the decades went by and the politics of Miller’s work moved further to the right. His All-Star Batman & Robin, which began in 2005, was largely received as a laughingstock and a source of such deathless memes as “I’m the goddamn Batman.”

It was in this atmosphere—and, of course, a post-9/11 climate—that Miller announced a new book, Holy Terror, Batman! He cheerfully described it as propaganda in which Batman “kicks Al-Qaeda’s ass.” The years after 9/11 were a time in which plenty of naked Islamophobia was permitted and even praised, but this was a bridge too far for most in the comics community, who criticized the concept as racist and juvenile.

Miller didn’t care, saying repeatedly that his intention was to “offend just about everybody.” But in 2008, he announced that it would no longer feature Batman but an original character called the Fixer (who looks just like Batman without the pointy ears), and would not be published by DC. Whether this was Miller’s decision or DC’s is unclear.

The book was eventually published in 2011 by Legendary Comics as simply Holy Terror. It was widely panned, with reviewers agreeing that it was just as Islamophobic as anticipated. Miller, who seems to have mellowed out considerably since then, said in 2018 that Holy Terror was “bloodthirsty beyond belief,” and that while he wouldn’t erase any of his past work, he is no longer capable of such a tirade.

Superman Renounces His American Citizenship

2011 was a controversial year in comics in general, and not just because of Holy Terror. DC and Archie stopped using the Comics Code Authority seal on their covers; they were the last publishers to do so, thus ending the CCA and 57 years of voluntary censorship. In September, DC launched their unpopular New 52 reboot.

But five months before that, in Action Comics #900, in a story by David S. Goyer, Miguel Sepulveda, and Paul Mounts, Superman announced that he was renouncing his American citizenship, so as to not cause international incidents when he went to other countries. Goyer has said that he didn’t expect the story (which wasn’t even the lead story in the issue) to be controversial.

Of course it was. Some people—and I’m sure you can guess which end of the political spectrum they were on—were livid that Superman was turning his back on “truth, justice, and the American way.” This is despite the fact that that particular phrase was originally just “truth and justice” when it first showed up in the Superman radio show of the 1940s; “the American way” was only added in 1942, when America was deep into World War II, and dropped again after the war. In a 1948 serial, Pa Kent tells Clark to fight for “truth, tolerance, and justice.” Hmmmm.

But we all know historical accuracy has never mattered to the likes of Fox News. DC’s then-publishers Dan DiDio and Jim Lee released an apologetic statement to The New York Post reiterating how very much Superman loved America, and editor Matt Idelson told a Superman fansite that the story wasn’t in continuity anyway, so it didn’t even matter. Swearsies!

The subject was never raised again in a comic…but these days, Superman’s slogan is “truth, justice, and a better tomorrow.” Also, he’s still what he has always been: an undocumented immigrant. Just sayin’.

This is just a sampling of the controversies that have inflamed the comics world over the past 75 years. Some are serious, some are silly, and some are somewhere in between, but it’s safe to say that neither the industry nor the fandom is likely to change any time soon. So here’s to another three-quarters of a century of controversy! And good luck to you, Spider-Man—you’re gonna need it.