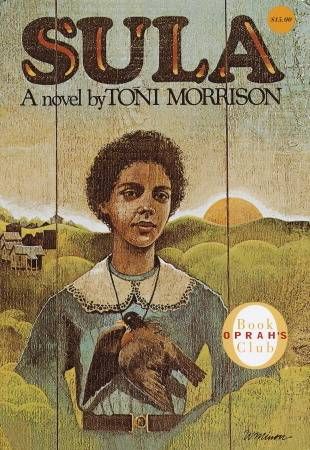

Morrison Marginalia: SULA

In preparation for the release of Toni Morrison’s new novel Home and our day-long celebration of same, I’ve set out to re-read all nine of her previously released novels. In the Morrison Marginalia series, I’m sharing notes from each book. See my comments on The Bluest Eye here.

____________________________

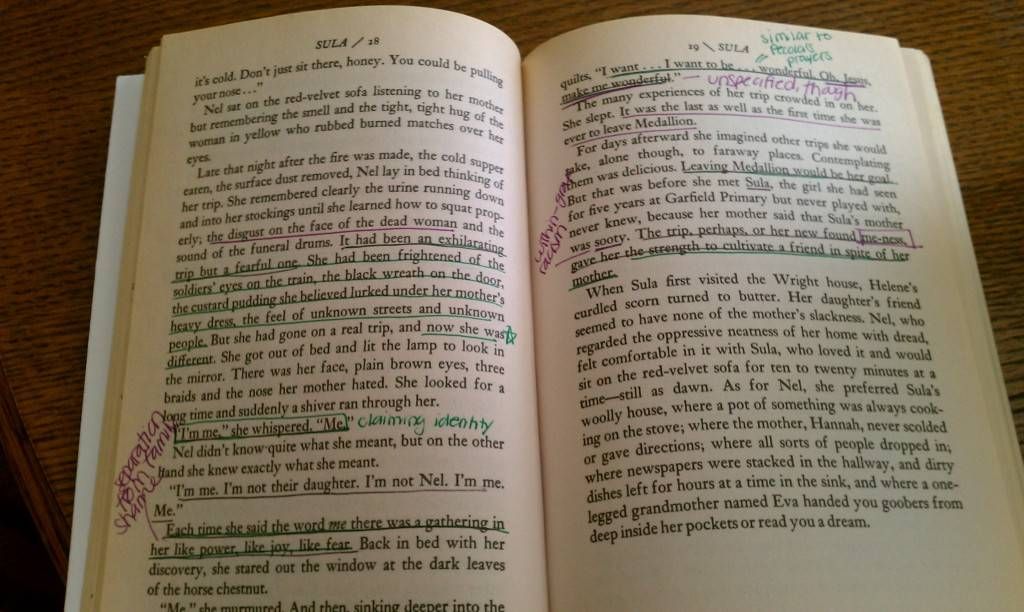

There are many more pages with notes than without in this volume. What you see here is the result of intense whittling.*

Pages 3-4: “It is called the suburbs now, but when black people lived there it was called the Bottom.” There is SO much here from the very beginning. We get the story of how the original residents of Medallion (how’s that for a loaded name?) were tricked into believing land was more fertile on top of the hill, and we know that in the future, “there will be nothing left of the Bottom.” Will we get to see the Bottom’s destruction, or just a snapshot of its life?

11-14: I love Shadrack and National Suicide Day. It sounds crazy–especially the parade–but “making a place for fear as a way of controlling it” is actually pretty brilliant. And his name! Thanks to a very memorable episode of Veggie Tales, I know it’s a reference to the biblical Shadrach, whose faith saved him when the king threw him into a fiery furnace. And fires figure large in this book, so….

Color politics aren’t a primary theme of Sula, but they’re present nonetheless. On page 20, Morrison tells us that Helene is a “pale yellow woman.”

28-29: Nel discovers her “me-ness,” and it gives her strength to defy her mother and create a friendship with wild, funky Sula. You can’t write about young people without digging into their self-concepts, and Morrison, of course, finds a new way to do it. Why talk about identity when you could talk about “me-ness”?

32: We learn that BoyBoy “liked womanizing best, drinking second, and abusing Eva third.” Sounds an awful lot like Cholly in The Bluest Eye. Is there a version of this man in every Morrison novel? And is the Suggs family down the street related to Baby Suggs in Beloved?

38: WTF is up with the deweys? Morrison wouldn’t talk about them so much, about how they arrive in Eva’s house very different and become indistinguishable, if they weren’t important, but I can never quite figure out what they represent. And holy smokes, can Morrison be weird!

43: Hannah’s wild blood and easy sexuality “taught Sula that sex was pleasant and frequent but otherwise unremarkable.” That’s such a perfect sentence, and it’s an important set-up for Sula as a proto-feminist who claims her right to enjoy her body and take pleasure from others’. The idea that sex is a source of power is critical to this novel, and it is drastically different from the depictions of sex in The Bluest Eye.

47: I first read this book in a college seminar, and we had the best debate about whether Eva’s killing Plum was an act of malice or mercy. I’ve always thought it was a mercy. I still do.

50: I’m pretty sure there’s a variation of these guys who gather outside the Time and a Hall Pool Hall to shoot the shit and look at women in every Morrison book. Even when the gaze isn’t a central theme, it is present.

58: “Together they worked until the two holes were one and the same.” This scene–which I know is a simulation of sex–never gets less strange. Bonus points for originality, Toni. Way better than a “the girls kiss each other to see what it’s like” scene.

76: Okay, so Hannah is on fire in the front yard. How did that happen? And can we talk about how awesome the image of Eva flying out the window is? I think Sula might be unfilmable–and thank goodness Oprah hasn’t gotten her mitts on it yet–but this scene would be great. I get so caught up in the language that I forget how cinematic Morrison can be.

92: “I don’t want to make somebody else. I want to make myself.” It’s reductive to say that any Morrison novel is about one thing, but if The Bluest Eye is the book about problematic standards of beauty, then Sula is the book about the burdens of being female, motherhood chief among them. Every time a character calls Sula selfish or tells her there’s something “not right” about her desire not to have children, I feel Morrison writing to me, writing the past into the present. I draw stars around this line every time. I just want to make myself. What’s so wrong with that? This is going in the file of future literary tattoos.

113: Teapot arrives on the scene and I have the sudden urge to catalog the crazy names in this book. In addition to Sula, we have a Shadrack, a Chicken Little, a Tar Baby (is he THE Tar Baby from the eponymous novel?), a BoyBoy. Who else? And where does Morrison get these names?

124: Speaking of unusual names, here’s Ajax. And of course, I can’t remember what his name is supposed to mean. Transcript of Actual Embarrassing Conversation Had In My Home:

Me: Who was Ajax, in mythology?

My Husband: I don’t remember. Son of somebody, God of something?

Twitter informs me that Ajax famously committed suicide, so I’ll set to pondering how that ties in with Shadrack and his day dedicated to the same.

142: Nel tells Sula, “You can’t do it all. You a woman and a colored woman at that. You can’t act like a man. You can’t be walking around all independent-like, doing whatever you like, taking what you want, leaving what you don’t.” And I want to scream OF COURSE SHE CAN. Morrison’s feminism shows in The Bluest Eye, but it is in full-on display here.

143: “I sure did live in this world.” File under: awesome last words. Also, nix the earlier tattoo note. THIS is what I want.

150: What the hell is dropsy? Just when I thought I could make it through the rest of the book without having to google something else…

153: Morrison puts it all out and refers to Sula’s “scorn for the role” of motherhood. She really doesn’t pull any punches.

174: The emotional thrust of the ending is really remarkable. Don’t we all know what “circles and circles of sorrow” means? Morrison is a master at the “show, don’t tell” thing that so many contemporary writers seem to struggle with.

Post-read gut check: I really adore this book. I identify with the feminist message, Sula’s decision not to have children (and the social repercussions of it), and Morrison’s depiction of women defining their identities through their relationships with each other on a very personal level, like I’m the choir Morrison is preaching to, and I want to shout “amen!” The Bluest Eye and Sula are incredible novels, but for Morrison, they’re just the warm-up act. I’m dragging my feet about starting Song of Solomon because I know the real work is about to begin.

*Page numbers refer to the 2002 Plume edition