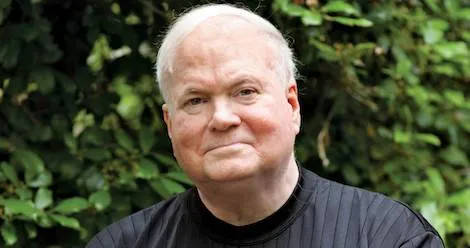

Loving and Losing Pat Conroy

Beach Music by Pat Conroy was the first modern adult novel I remember reading. I was a teenager, and I’d quickly jumped from young adult novels to the heavy, heady classics. I needed a reprieve from working my way through the canon, and I’d often stand in front of my parents’ bookshelves and ask for something to read, only to refuse all of my mother’s suggestions with a heavy dose of teenage sighing.

Loosely autobiographical fiction is nothing new, but for Conroy it was a way of life. Many writers can’t mine their lives for more than a book or two. Conroy had lifetimes worth of stories, so many it almost defies belief. He was often accused of putting too much in his plots and stories, but he could almost always respond by saying, “That really happened.” The abusive military father, the harrowing hazing of the Citadel, so much loss and mental illness and suicide. Conroy returned to his demons in book after book, none of them were ever quite laid to rest. And yet, while reading his books could be harrowing, most of them are all about love. He writes of families we’re born with and those we create, I can think of few other examples of friendships as fierce as those found in his novels. Conroy became one of those rare larger-than-life authors, and I know it’s because of the warmth and love that radiated through his writing, that seemed to reach out of the page..

If you haven’t read Conroy, it doesn’t much matter where you start. You’ll find the same big beating heart and heightened drama among his pages. But you certainly couldn’t go wrong starting the way I did, with Beach Music, the closest he ever came to a magnum opus. There’s Beaufort, South Carolina. There’s a family’s painful past and another’s painful present. There’s loved ones lost to alcoholism, suicide, war, and mental illness. And there’s the Great Dog Chippie, of course, my favorite character (and my mother’s, too) that says so much about the author.

Conroy himself had a dog named Chippie as a boy. The fictional version of Conroy in Beach Music, Jack McCall, tells his daughter Leah stories of the Great Dog Chippie. This imaginary Chippie he creates for her is the hero of the family, a way for Jack to re-write the tragedies from his life and turn them into triumphs. When Leah meets Jack’s mother for the first time, Leah is excited to meet someone else who knew Chippie, who can tell her more stories. “What’s to tell,” his mother says. “Chippie was a mutt. A stray.”

Jack does just what Conroy always did and speaks his own fictionalized truth: “Chippie was a magnificent beast. Fearless, brilliant, and a great defender of the McCall family.”

That need to rewrite your own story, to explore your life’s great tragedies through narrative, it’s something few have ever done as well and as thoroughly as Conroy. Losing him makes me long for his downtrodden mothers, broken boys, tyrannical fathers, lost sisters, bosom friends, and heroic mutts. I’ve spent so many hours with his words, with the smell of seawater and fried shrimp in my nose, a view of the Carolina lowcountry in my mind’s eye. Marshes and herons, streets with stately old houses or aging shacks.

If this were a truly fitting tribute, it’d be pages upon pages long. (Conroy’s first draft of Beach Music that he sent to his editor was 2,100 pages.) A truly fitting tribute would be stuffed to the brim with tragedy and the pain that never quite leaves you. But my time with Conroy was just joy, tinged with sadness, but joy nonetheless. I’ll miss him terribly. But the sadness is brightened by the memories of his books and the knowledge that they are still here for me any time I may want to read them. His voice and his words and his life are still there and they always will be.