The Gutenberg Bible and How to See it Online

Many people know something about the Gutenberg Bible, the first book to be printed using moveable type. I vaguely remember learning about it in a history class. If you don’t, you can find some fast facts here. At the time I learned about it, I mistakenly thought it was the first book ever printed. That is not accurate—shocking that my middle school self did not register this fact. Just kidding. Those many years ago I thought that history was boring, so that just goes to show what I knew at the time.

The First Printed Book

Chinese woodblock printing was in use prior to the Gutenberg Bible by many centuries. According to the British Library’s website, the first known woodblock printed book is a copy of The Diamond Sutra dated 868, which is now housed in the BL’s collection. There is a short dedication at the end noting it was to be distributed on behalf of the commissioner’s parents. If you’re curious, you can take a look at it here. Susan Whitfield, a historian and BL librarian, also gave a 10-minute talk on it that you can listen to here.

While most sutras were eventually printed this way, there is also a beautiful hand-lettered copy of the sutra – much younger than the one in the BL – in the New York Metropolitan Museum of Art’s Collection. The Met’s copy has some lovely illustrations and some of the text is also woodblock printed. It has been digitized and is available for perusal here. You don’t need to read Chinese to appreciate its beauty.

Where You Can See a Gutenberg Bible

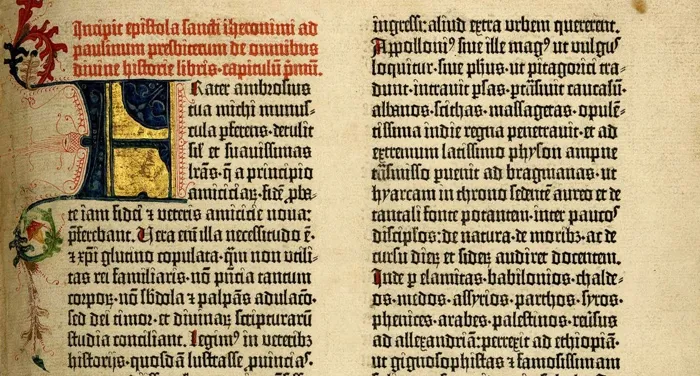

As for the Gutenberg Bible, it is unclear how many copies were originally produced. There are estimated to be around 40 still extant from Johann Gutenberg’s original printing done around 1455. According to the U.S. Library of Congress, there are only three perfect vellum copies left in existence, one of which is part of the LOC’s collection.

According to Encyclopedia Britannica, the other two are in the Bibliothèque Nationale de France (available here) and the BL. There are also nearly-complete copies held by several libraries. In the U.S., these include Harvard University, Yale University, and the New York Public Library (NYPL). According to the NYPL, the copy in its collection was the first to arrive in the U.S. in 1847 and was accorded such respect that “instructions [were sent to] New York that the officers at the Customs House were to remove their hats on seeing it.” I know people don’t wear hats much anymore in a lot of places, but I like the image of these individuals respectfully uncovering their heads.

Another library with copies is the Morgan Library and Museum (also in New York City). There are actually three copies at the Morgan, one copy on vellum and two copies on paper. Of the latter, one volume is the Old Testament which can be seen here on their website.

What About Other Old Books?

While I find old books and manuscripts to be fascinating, I have never wanted to handle one. Touching one would be far too much pressure for me. What if I dropped it? How would I feel if I ripped it? What if it just fell apart in my hands? The answer is I’d feel terrible. However, I like the idea of reading about old books and manuscripts, and studying them digitally. If the Gutenberg Bible piques your interest, you might like to learn about another old text – in this case handwritten.

The Birmingham Qur’an is not complete, but it is one of the few partial Qur’anic manuscripts to have been radiocarbon dated to “the period between 568 and 645 with 95.4% probability” according to the University of Birmingham website. If you’re curious, you can see an explanation of what the radiocarbon dating means exactly and an image of the manuscript as seen through multi-spectral imagining here. The former gives us the likely time of the skin’s preparation. The latter process tells us that the skin was not used for any other writing before the one currently seen on its surface. Pretty cool, right?

If your early Islamic history is a little rusty, all this means that the pages we have today were only used to inscribe the Qur’an and likely written during the Prophet Muhammad’s lifetime or some years after his death in 632. It’s amazing to think of how some texts this old are still with us today.

If you’d like to see something from the New Testament too, you can also learn about the Book of Kells here. Happy reading!