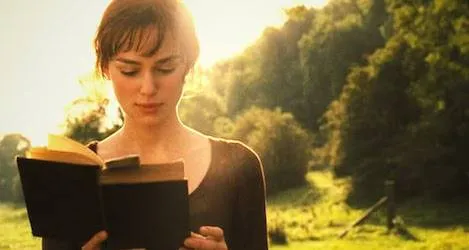

Elizabeth Bennet: Manic Prideful Dream Girl? Of Course Not

Recently over on Lit Reactor, Leah Rhyne wrote a column asking if Elizabeth Bennet, the much-beloved heroine of Jane Austen’s Pride and Prejudice, is in fact a dreaded Manic Pixie Dream Girl. Coined by film critic Nathan Raban, the term refers to a female character, usually written by a man, who exists to be a bubbly, free-spirited adventure for the brooding, sad-sack male protagonist. Charming but vacuous, she teaches him to embrace the whimsical side of life but has absolutely nothing going on for herself.

Rhyne says right up front that the Manic Pixie Dream Girl (or, to use her abbreviation, the MPDG) is pretty much by definition written by a man, and Elizabeth Bennet obviously wasn’t, so she can’t actually be a MPDG. She then completely disregards her own point to continue with her thesis, but I think the gender of the writer is really crucial here, so let’s stick a pin in that.

Rhyne then outlines the specific parameters of an MPDG and analyzes Lizzy accordingly:

A MGDG does not pursue her own happiness

Lizzy, Rhyne claims, does not pursue her own happiness; she’s more concerned with bantering with her father and listening to her sister’s “lovelorn musings” about Mr. Bingley. In actual fact, Jane rarely discusses Bingley, and Lizzy enjoys bantering with her father – her love of a witty conversation is one of her most prominent characteristics. Lizzy isn’t performing any act of self-sacrifice. She’s living the life she chooses to.

What greater proof is there than her decision to turn down two proposals that her mother would love for her to accept, and then later refusing to turn down a proposal she wants? “I am only resolved to act in that manner, which will, in my own opinion, constitute my happiness, without reference to you, or to any person so wholly unconnected with me,” she tells Lady Catherine. She doesn’t sound like a quirky martyr to me.

A MPDG will never grow up

Rhyne accuses Lizzy of “refusing to grow up” for remaining unmarried at age twenty, even though she hasn’t been proposed to until Mr. Collins gives it a go, and dings her for living in the house where she grew up, as if an unmarried young woman in Regency England could just find an apartment to rent with Charlotte Lucas on Craigslist. Context matters.

A MPDG has no discernable inner life

Rhyne admits that her thesis “falls apart completely” here, as the book is mostly (though not solely, as she claims) from Elizabeth’s point of view. But does this just make Lizzy “a perfect example of how to completely subvert a common character trope?”

No, because the trope didn’t exist then, so Austen couldn’t subvert it. Moving on!

A MPDG is there to provide life lessons

I’ll give Rhyne this: Lizzy does help Darcy grow a sense of humor, which is one of the hallmarks of an MPDG. She is not, however, the “wisest character in the tale,” as Rhyne claims. She’s frequently wrong: about Darcy, about Wickham, about Charlotte, about Jane and Bingley. She’s certainly more charming at the start of the novel than Darcy, which makes it easy to miss that she grows as much as he does over the course of the story. Pride and Prejudice isn’t a story about a feisty imp of a girl teaching a sad man how to love; it’s a story about two flawed people learning to meet each other halfway, which is why it’s stood the test of time as one of the greatest love stories ever told.

What bothers me so much about this article is not that Lizzy isn’t a Manic Pixie Dream Girl, as Rhyne freely admits in her conclusion. What bothers me is subjecting a female character who readers (especially women) love to an arbitrary litmus test for the sake of a clickbaity headline, and using it to draw a scaremonger-y conclusion about what you as a writer must never do! Or else!

In doing so, Rhyne places “Manic Pixie Dream Girl” alongside “Mary Sue” and “Strong Female Character” as terms that once identified a specific trope, but which have been repurposed as a way to dismiss female characters as “bad.” Rey is a Mary Sue, Wonder Woman is a Strong Female Character, and Elizabeth Bennet, maybe, is a Manic Pixie Dream Girl. You thought you liked this character, women, but can’t you see that you were wrong and actually she sucks?

It’s here that the gender of the writer becomes crucial, because the term Manic Pixie Dream Girl was coined to describe a heterosexual male fantasy object. The whole point is to call out a specifically male behavior; one might as easily accuse Austen of manspreading. (She would never!)

Instead of taking on the crimes of sexist male writers, let’s resist the urge to police women, real and fictional, this way. Let’s celebrate the strengths of a brilliantly-drawn female protagonist instead of warning young women away from imaginary pitfalls. Leave the Manic Pixie Dream Girl accusation where it belongs, and simply enjoy a heroine readers have loved for generations.