Comic Vs. Book: TEN DAYS IN A MAD-HOUSE

Everyone knows that books can be adapted into movies. It happens all the time. But did you know they can be adapted into graphic novels, too? In this series, I’ll be taking a look at classic novels and their illustrated counterparts to determine what each did well, what each did wrong, and how they approach the same story decades apart and in such different media.

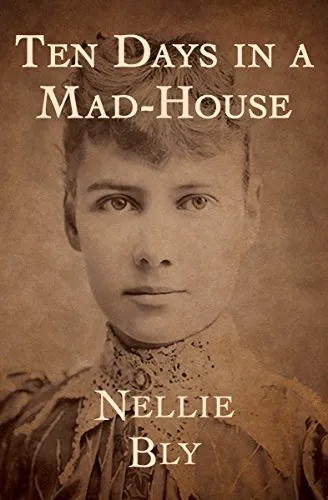

So far, all the books I’ve covered have been works of fiction. Today, I’m looking at a nonfiction book for the first time: Ten Days in a Mad-House; or, Nellie Bly’s Experience on Blackwell’s Island, written by Nellie Bly in 1887.

NOTE: Both book and comic use terminology that is now outdated and even offensive with regard to mental illness. They also contain detailed depictions of abuse against women.

The original book was written at a time of profound ignorance of all things relating to mental health and healthcare — that’s partly why Bly wrote the book — and Bly’s sympathies are clearly with the patients, even if the language available to her at the time has not aged well.

The Book

We start with a little backstory as Bly, “the New York World‘s girl correspondent,” agrees to infiltrate Blackwell Island Insane Asylum. Historically, the island was a dumping ground for all the people that New Yorkers didn’t want to deal with, including women who were poor, mentally ill, or just plain loud. Though she had heard rumors of abuse and mistreatment on the island, Bly admits that she thought they were “wildly exaggerated or else romances.”

After conning her way into the asylum, Bly was horrified to find that conditions were worse than she could have imagined. In her writing, she expresses disgust for the so-called professionals in charge of the place, as well as great sympathy for the patients she came to care so much for that she felt guilty when she left them behind.

At the same time, there’s something very professional, almost clinical—though certainly not detached—in the way she relates her experiences. Chapter 13 is matter-of-factly titled “Choking and Beating Patients,” for example. She clearly wanted to maintain an air of authority to make her work more trustworthy to readers who, like Bly initially, might be skeptical about the extent of the abuse happening on Blackwell’s Island.

The abuses Bly describes are every bit as infuriating and gut-wrenching as they were in the 1880s, but for me and anyone else who knows anything about history, the shock has long since worn off. We are all very aware of the horrific conditions mental health patients were subjected to, and for that, we can thank Bly.

Even the revelation that Bly was not the only “sane” woman locked up in Blackwell is not surprising: even today, women’s healthcare can be a nightmare of misdiagnosis by ignorant, misogynistic doctors.

The book’s chapters are short, and the language is pretty accessible, even by modern standards. In retrospect, I shouldn’t have been surprised: Bly’s intention was to raise awareness and public outcry about how the mentally ill were being treated. The best way to do that was by making her writing easy to read. The book isn’t that long, either; it’s less than 100 pages, not counting the unrelated bonus material in the back.

Since this work is in the public domain, you can read it free on Project Gutenberg if you’re curious.

The Comic

Adapted by Brad Ricca and Courtney Sieh, the graphic adaptation of Ten Days in a Mad-House was released in 2022. In many ways, it’s very faithful to the original, right down to the ad for corsets included at the front.

The changes made are generally to provide us with a deeper glimpse into Nellie’s own life and psyche. My favorite example of this occurs after Nellie is given a cold and filthy bath by uncaring nurses. As she stands before a mirror, shivering and half-naked, she sees a reflection of her normal self, calm and neatly dressed. Her reflection provides much-needed encouragement during a brutal and dehumanizing experience.

Scenes like this show the differing goals of each book’s creators. While the purpose of the original book was to expose the horrific state of women’s mental healthcare, the purpose of the adaptation is to tell the story of a brave journalist who risked her own health to get an important story.

The art is very expressive and almost resembles a horror movie. The nurses are “shot” from a low angle, their faces obscured by hatch lines, for instance. Even though it’s in black and white, I wouldn’t say it evokes the illustrations included in the original. Sieh has a much harder, more angular style that captures the harshness of life on Blackwell.

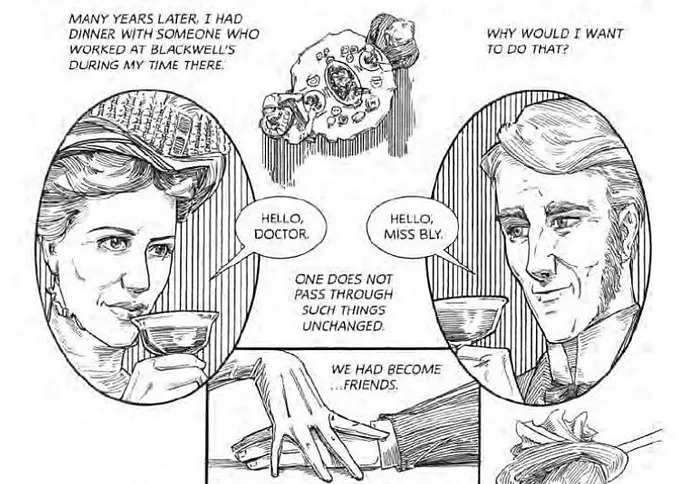

The only thing that struck me as odd was the comic’s depiction of Bly’s relationship with Dr. Ingram, a sympathetic but ineffectual doctor at the institution. In her book, Bly says that “only a girl can sympathize with me in my position” of having to fake mental illness in front of such a handsome man. The comic takes this a step further by having them gently touch hands over the dinner table during a pointless epilogue in which Bly states that they have become “friends” (quotation marks heavily implied) in the years since the exposé.

There were, apparently, rumors of a romance between the two, even at the time. And I get that they want to round out Nellie’s character a bit. But it seems weird that they would indulge in unsubstantiated gossip in a book that originated with a determination to tell the unvarnished truth.

The Takeaways

Both versions of the story are well worth a read! They fulfill their objectives admirably, bringing the full horror of a difficult subject home to the reader. Which version you choose really just depends on whether you feel like reading a prose book or a graphic novel and whether you like Sieh’s art style or not.

Check out previous Comic vs. Book showdowns: To Kill a Mockingbird, The Hobbit, Treasure Island, and Great Expectations