The Appeal of the Hypnotically Dull Novel

This content contains affiliate links. When you buy through these links, we may earn an affiliate commission.

Boring is bad, right?

Well, there’s a trend toward celebrating, in a self-deprecating manner, the low-key pleasures of the obscure and mundane. The BBC’s Boring Talks podcast, for instance, devotes loving attention to things as pedestrian as wooden pallets. The Boring Conference is a sold-out event. The Object Lessons series shows that taken-for-granted items like shipping containers and driver’s licenses contain a wealth of fascinating stories. And the Japanese reality show Terrace House has been called “extremely, hypnotically boring”—in a positive review.

In novels, dullness is one of the main reasons to give up on a book a few pages in. I find that reading to the end, in the hope of a grand payoff making the slow slog worthwhile, is generally disappointing.

In novels, dullness is one of the main reasons to give up on a book a few pages in. I find that reading to the end, in the hope of a grand payoff making the slow slog worthwhile, is generally disappointing.

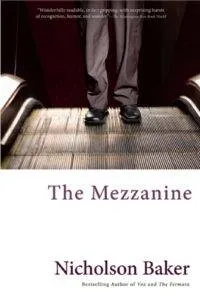

Yet some novels are compelling not in spite of their tedium, but—in a perverse way—because of this tedium. The novels of Nicholson Baker are a good case in point. These have the flimsiest of premises: in The Mezzanine, an office worker sees that one shoelace is more frayed than another, and ruminates over this for the entire book. In Room Temperature, a father feeding his newborn daughter allows his mind to wander. That’s it. Nothing happens. The books take place almost entirely in the unexciting narrators’ heads…and that’s precisely what makes them interesting. Tracing a chain of thoughts, and appreciating the simple curiosity that to me is one of the most enlivening aspects of human existence, is what these books (quietly) revel in.

Yet some novels are compelling not in spite of their tedium, but—in a perverse way—because of this tedium. The novels of Nicholson Baker are a good case in point. These have the flimsiest of premises: in The Mezzanine, an office worker sees that one shoelace is more frayed than another, and ruminates over this for the entire book. In Room Temperature, a father feeding his newborn daughter allows his mind to wander. That’s it. Nothing happens. The books take place almost entirely in the unexciting narrators’ heads…and that’s precisely what makes them interesting. Tracing a chain of thoughts, and appreciating the simple curiosity that to me is one of the most enlivening aspects of human existence, is what these books (quietly) revel in.

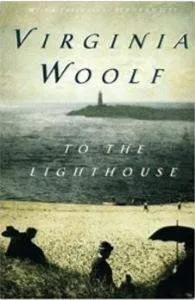

This may be considered sacrilegious, but Virginia Woolf’s novels can also be simultaneously tiring and fascinating. To the Lighthouse exists almost entirely in the gauzy world of consciousness, which isn’t exactly an action-packed expressway. But it’s infinitely rewarding.

Monotony in a novel can also feel deliberate, if it’s capturing the monotony of real life in a way that unrealistic fiction glosses over. Hideo Yokohama’s Six Four does this for police work, which is so often sensationalized in books and movies, despite the abundance of paperwork that makes up much of this job. Six Four feels plodding in the same way that it would feel plodding to be, say, a press director waiting for ages in a police station’s bathroom cubicle, hoping to hear the distinctive water tap use pattern of a certain high-ranking police officer, in order to ask him some questions. (And yes, this is a thing that happens in the book.) The possibility that reporters will issue a complaint is the main engine of suspense for much of the novel, and the present-day crime doesn’t take place until past page 450.

This may be considered sacrilegious, but Virginia Woolf’s novels can also be simultaneously tiring and fascinating. To the Lighthouse exists almost entirely in the gauzy world of consciousness, which isn’t exactly an action-packed expressway. But it’s infinitely rewarding.

Monotony in a novel can also feel deliberate, if it’s capturing the monotony of real life in a way that unrealistic fiction glosses over. Hideo Yokohama’s Six Four does this for police work, which is so often sensationalized in books and movies, despite the abundance of paperwork that makes up much of this job. Six Four feels plodding in the same way that it would feel plodding to be, say, a press director waiting for ages in a police station’s bathroom cubicle, hoping to hear the distinctive water tap use pattern of a certain high-ranking police officer, in order to ask him some questions. (And yes, this is a thing that happens in the book.) The possibility that reporters will issue a complaint is the main engine of suspense for much of the novel, and the present-day crime doesn’t take place until past page 450.

Some English-language reviewers seem to find that the “educational exoticism” of Six Four’s Japanese setting makes up for this monotony, but that’s missing the point. (That kind of comment also smacks of a tired orientalism: “Oh, isn’t it quirky, it’s so weird and other and worthwhile only for that reason!”) It’s interesting to follow the procedural details of a book like this, if you’re a person interested in procedural details and how to spin these together.

As well, a hypnotically dull novel offers a good opportunity to focus on mood. Franz Kafka is a master of this, using labyrinthine, nightmarish settings like the one in The Trial to create an oppressive atmosphere, rather than a tightly knit plot. There’s a tedium borne out of repetition, also present in a graphic novel like Nick Drnaso’s Sabrina, that sharply captures the texture of a certain kind of life (or dream-life).

The appeal of the hypnotically dull novel is that it differs from just a dull novel, by spinning something refreshing or thought-provoking out of boredom. A hypnotically dull novel is different from a novel that tries to be engaging and fails. What are some other examples of hypnotically dull novels?

Some English-language reviewers seem to find that the “educational exoticism” of Six Four’s Japanese setting makes up for this monotony, but that’s missing the point. (That kind of comment also smacks of a tired orientalism: “Oh, isn’t it quirky, it’s so weird and other and worthwhile only for that reason!”) It’s interesting to follow the procedural details of a book like this, if you’re a person interested in procedural details and how to spin these together.

As well, a hypnotically dull novel offers a good opportunity to focus on mood. Franz Kafka is a master of this, using labyrinthine, nightmarish settings like the one in The Trial to create an oppressive atmosphere, rather than a tightly knit plot. There’s a tedium borne out of repetition, also present in a graphic novel like Nick Drnaso’s Sabrina, that sharply captures the texture of a certain kind of life (or dream-life).

The appeal of the hypnotically dull novel is that it differs from just a dull novel, by spinning something refreshing or thought-provoking out of boredom. A hypnotically dull novel is different from a novel that tries to be engaging and fails. What are some other examples of hypnotically dull novels?

In novels, dullness is one of the main reasons to give up on a book a few pages in. I find that reading to the end, in the hope of a grand payoff making the slow slog worthwhile, is generally disappointing.

In novels, dullness is one of the main reasons to give up on a book a few pages in. I find that reading to the end, in the hope of a grand payoff making the slow slog worthwhile, is generally disappointing.

Yet some novels are compelling not in spite of their tedium, but—in a perverse way—because of this tedium. The novels of Nicholson Baker are a good case in point. These have the flimsiest of premises: in The Mezzanine, an office worker sees that one shoelace is more frayed than another, and ruminates over this for the entire book. In Room Temperature, a father feeding his newborn daughter allows his mind to wander. That’s it. Nothing happens. The books take place almost entirely in the unexciting narrators’ heads…and that’s precisely what makes them interesting. Tracing a chain of thoughts, and appreciating the simple curiosity that to me is one of the most enlivening aspects of human existence, is what these books (quietly) revel in.

Yet some novels are compelling not in spite of their tedium, but—in a perverse way—because of this tedium. The novels of Nicholson Baker are a good case in point. These have the flimsiest of premises: in The Mezzanine, an office worker sees that one shoelace is more frayed than another, and ruminates over this for the entire book. In Room Temperature, a father feeding his newborn daughter allows his mind to wander. That’s it. Nothing happens. The books take place almost entirely in the unexciting narrators’ heads…and that’s precisely what makes them interesting. Tracing a chain of thoughts, and appreciating the simple curiosity that to me is one of the most enlivening aspects of human existence, is what these books (quietly) revel in.

This may be considered sacrilegious, but Virginia Woolf’s novels can also be simultaneously tiring and fascinating. To the Lighthouse exists almost entirely in the gauzy world of consciousness, which isn’t exactly an action-packed expressway. But it’s infinitely rewarding.

Monotony in a novel can also feel deliberate, if it’s capturing the monotony of real life in a way that unrealistic fiction glosses over. Hideo Yokohama’s Six Four does this for police work, which is so often sensationalized in books and movies, despite the abundance of paperwork that makes up much of this job. Six Four feels plodding in the same way that it would feel plodding to be, say, a press director waiting for ages in a police station’s bathroom cubicle, hoping to hear the distinctive water tap use pattern of a certain high-ranking police officer, in order to ask him some questions. (And yes, this is a thing that happens in the book.) The possibility that reporters will issue a complaint is the main engine of suspense for much of the novel, and the present-day crime doesn’t take place until past page 450.

This may be considered sacrilegious, but Virginia Woolf’s novels can also be simultaneously tiring and fascinating. To the Lighthouse exists almost entirely in the gauzy world of consciousness, which isn’t exactly an action-packed expressway. But it’s infinitely rewarding.

Monotony in a novel can also feel deliberate, if it’s capturing the monotony of real life in a way that unrealistic fiction glosses over. Hideo Yokohama’s Six Four does this for police work, which is so often sensationalized in books and movies, despite the abundance of paperwork that makes up much of this job. Six Four feels plodding in the same way that it would feel plodding to be, say, a press director waiting for ages in a police station’s bathroom cubicle, hoping to hear the distinctive water tap use pattern of a certain high-ranking police officer, in order to ask him some questions. (And yes, this is a thing that happens in the book.) The possibility that reporters will issue a complaint is the main engine of suspense for much of the novel, and the present-day crime doesn’t take place until past page 450.

Some English-language reviewers seem to find that the “educational exoticism” of Six Four’s Japanese setting makes up for this monotony, but that’s missing the point. (That kind of comment also smacks of a tired orientalism: “Oh, isn’t it quirky, it’s so weird and other and worthwhile only for that reason!”) It’s interesting to follow the procedural details of a book like this, if you’re a person interested in procedural details and how to spin these together.

As well, a hypnotically dull novel offers a good opportunity to focus on mood. Franz Kafka is a master of this, using labyrinthine, nightmarish settings like the one in The Trial to create an oppressive atmosphere, rather than a tightly knit plot. There’s a tedium borne out of repetition, also present in a graphic novel like Nick Drnaso’s Sabrina, that sharply captures the texture of a certain kind of life (or dream-life).

The appeal of the hypnotically dull novel is that it differs from just a dull novel, by spinning something refreshing or thought-provoking out of boredom. A hypnotically dull novel is different from a novel that tries to be engaging and fails. What are some other examples of hypnotically dull novels?

Some English-language reviewers seem to find that the “educational exoticism” of Six Four’s Japanese setting makes up for this monotony, but that’s missing the point. (That kind of comment also smacks of a tired orientalism: “Oh, isn’t it quirky, it’s so weird and other and worthwhile only for that reason!”) It’s interesting to follow the procedural details of a book like this, if you’re a person interested in procedural details and how to spin these together.

As well, a hypnotically dull novel offers a good opportunity to focus on mood. Franz Kafka is a master of this, using labyrinthine, nightmarish settings like the one in The Trial to create an oppressive atmosphere, rather than a tightly knit plot. There’s a tedium borne out of repetition, also present in a graphic novel like Nick Drnaso’s Sabrina, that sharply captures the texture of a certain kind of life (or dream-life).

The appeal of the hypnotically dull novel is that it differs from just a dull novel, by spinning something refreshing or thought-provoking out of boredom. A hypnotically dull novel is different from a novel that tries to be engaging and fails. What are some other examples of hypnotically dull novels?