Troubles in Adaptation: The 2013 Adaptation of THE GREAT GATSBY

I think a lot about the class issues in The Great Gatsby. When I first read it, Gossip Girl (the modern answer to The Great Gatsby) was one of the most popular shows on television. However, the recession of 2008 had also just ravaged so many people’s savings and prospects. It seemed like the very rich had receded into the background again instead of being so visible. The Great Gatsby similarly analyzed a major break the way the wealthy lived. At the same time, Hollywood films offered deliberate escapism in the desolate 1930s. Similarly, in the early 2010s, we all started to get really into watching rich people fall apart on television (i.e. the Real Housewives Expanded Universe).

We’re in a moment where class distinctions have never been worse. The rich have the ability to create bubbles for themselves, and have to consider if they should continue allowing support staff into their homes. Service workers who helped maintain the lifestyles of the extremely wealthy are now more obvious to us because their work has been radically altered or completely stopped. When I read The Great Gatsby again in my early 20s, I could only think about the staff that put together Gatsby’s house for parties every night, because I felt I would be more likely to clean up after a party like that than attend it.

While celebrities entertain us from their beautiful homes on Zoom and Instagram Live, those of us who have nothing to do but watch can’t help but notice how much more space they have than the rest of us. It’s a rare position of voyeurism, similar to Nick Carraway’s ability to sweep through the excessive lifestyles of the rich. When looking at a celebrity’s beautiful home behind their beautiful head, I can’t help but think about the world F. Scott Fitzgerald was commenting on. I’m also drawn to reconsider Baz Luhrmann’s adaptation of The Great Gatsby.

The Great American Novel in Movie Form

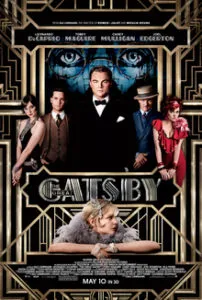

Judging the 2013 film The Great Gatsby as an adaptation is an exercise in immense frustration. Every important moment of the novel by F. Scott Fitzgerald occurs in the film with distinct Luhrmannian opulence, with every actor doing their best please-nominate-me scene chewing. Leonardo DiCaprio as Jay Gatsby pushes very hard to embody the famous character, but without much nuance. Joel Edgerton and Carey Mulligan as Tom and Daisy Buchanan embody their roles well enough, but they also have the careful, over-pronounced r’s of non-American actors attempting not to break. With the involvement of an over-the-top director, the musical direction of Jay-Z, and the roster of A-list actors, the film is bursting with high-quality ingredients.

The movie itself had no shortage of high expectations going in. Luhrmann films are both hugely successful and cult-like in their continuing popularity. His version of Romeo + Juliet still sticks out as a uniquely fun interpretation of the classic Shakespearean tale, and Moulin Rouge! gave us a refreshingly vital approach to a Hollywood musical. Since he had taken stories so many were familiar with and made them fun, The Great Gatsby seems like a good fit with his œuvre. The book makes its way into millions of American literature syllabi, and Hollywood definitely felt it was ready for a refresh after the most recent 1974 version, if you’re going by the 30 year cycle.

When I was preparing to read The Great Gatsby for my 10th grade English class, both of my parents separately explained their favorite bits to me. Mom grabbed the book out of my hands and read the passage about the whirling curtains in the white house out loud, then explained that the wind brought them crashing into each other’s lives and Tom shutting the windows represented that he was a controlling monster. This scene is perfectly replicated the Baz Luhrmann film. Dad remarked on the fact that F. Scott Fitzgerald, like Nick, never felt comfortable around the old money east coast intellectuals he encountered at Princeton. This is less present in the film.

It seems like a no-brainer that an adaptation of a book about excess should boast excess in its production as well. However, this conception of excess is where the book and movie disconnect. The book is more invested in the ugly, sallow parts of Gatsby’s displays, while the movie basks in the Hollywood glamour of it all. Tobey Maguire takes a befuddled approach to his portrayal of Nick, constantly looking confused or upset. Maguire himself was also a known quantity: he had starred in many blockbuster films, was in the disgustingly named “Pussy Posse,” and at that point was still beloved for portraying Spider-Man. Nick’s outsider status would be much better portrayed by a Hollywood newcomer: this makes him both an unknown quantity and gives him the automatic ability to look at a Hollywood giant like DiCaprio with fascination. With Maguire as Nick, there was a smaller difference for me in their preexisting differences. Nick’s outsider status is less obvious in the film, with a small amount of voiceover.

Part of the reason The Great Gatsby is so popular among English teachers is because of the many rhetorical devices present in the novel, especially with the metaphors tying very neatly into the overarching theme of the lost American Dream. The uncut books of the library, the eyes of T.J. Eckelburg, or the green light can easily teach essay-writing through the thematic significance of each of these visual metaphors. The books of Gatsby’s grand library have never been read so they are empty of meaning, while the eyes watch over the secret sins, and the green light will always be ungraspable because desires are always just out of reach. Attempting to translate these somewhat heavy-handed images to film can’t be easy, but maybe that is the issue with trying to adapt The Great Gatsby. It is simply too well-known and too well-studied to allow wiggle room in the imagery and storytelling.

The glossy, perfect finish of the film is also missing the ugliness at the edges of Gatsby’s world. Even the scenes with Myrtle and the morning after the parties are lovingly arranged, with characters breaking into diegetic song. The Moulin Rouge style of magical realism feels at odds with the searing critique upper class excess and carelessness inherent to Fitzgerald’s book. As Matt Zoller Seitz said at the time, the movie just didn’t work, not because of his “stylistic gambits,” but because of “his inability to reconcile them with an urge to play things straight.”

We All Have An Interpretation

When Nick Carraway handwrote “The Great” over his printed manuscript entitled “Gatsby” at the end of the movie, I nearly screamed in frustration. I had never seen Gatsby’s creation of a completely false life as a positive endorsement of the American Dream, and I don’t think Nick in the book thought that either. The final “great” addition turns the movie to Gatsby’s side, attempting to explain to us that Gatsby’s selfish, multi-year indulgence was a great thing because he did it for love. The movie is stripped of meaning by failing to recognize the emptiness of Gatsby’s self-creation. It was not a great thing for him to create a fake life to pursue a woman he’d transferred his entire life’s purpose onto a long time ago.

Piling more on top of a story doesn’t make it better. The Great Gatsby is a relatively short novel, beloved for its simple, incisive portrayal of the reckless over-consumption of 1920s. The overloading of talent and design in Luhrmann’s film serves to show us what Fitzgerald was trying to critique without understanding the delusional nature of Gatsby’s attempt to hold onto the perfect American Dream.

I think about The Great Gatsby a lot right now because the structures of wealth are falling down around us. At the very least, more people are becoming aware of the structures that allow the wealthy to hide themselves away from the dangers to which the rest of us are subjected. Fitzgerald’s critique of the excessive wealth of the roaring ’20s came out in 1925, so a little while before The Great Depression ravaged so many lives. There was a bit of a lead-up to distaste for the rich in the form of jokes about bringing back the Guillotine. It is inevitable that we were going to hit another bust in the economy, but the distribution of the effects of this economic downturn are extremely stark.

I will continue to think about The Great Gatsby because it hits so accurately what we see in American life over and over again. I’m thinking about the 2013 film adaptation because I can’t help but think about how celebrities are attempting to stay “relatable” right now in a world that is so uneven. Celebrities might despair the production halt because they are bored trapped in their mansions, but thousands have lost their jobs and don’t have a restart date in sight. I would really like to never have to see the beautiful, minimalist interior of a celebrity home again.