The Paradox of Harley Quinn

This content contains affiliate links. When you buy through these links, we may earn an affiliate commission.

I first read Batman: Mad Love in high school. I was starting to be vaguely interested in superheroes, and a friend of mine lent it to me. “You need to read this,” she said, handing it to me the way someone would handle a sacred text. “I am Harley Quinn.”

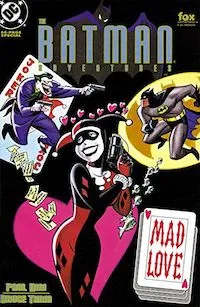

If you’re not familiar with it, Mad Love is a one-shot comic from 1994 by Paul Dini and Bruce Timm, set in the continuity of the then-running Batman: The Animated Series. It tells the origin story of Harley Quinn, the Joker’s bubbly Girl Friday, who had been introduced two years prior in the cartoon and quickly became a fan favorite. Harleen Quinzel, psychiatrist, gets a job at Arkham Asylum and finds herself falling for the Joker thanks to the sob stories he tells her. She embarks on a life of crime for him, and ultimately almost succeeds in killing Batman. Enraged that she’s come closer to his goal than he ever has, the Joker throws her through a window, landing her in the hospital wing of Arkham.

On the comic’s famous final page, Harley muses sadly on where her love for a violent killer has brought her. “He hit me…” she says. Then she notices the flower he left by her bedside, and brightens: “And it felt like a kiss!” (A reference to the disturbing 1962 song by the same name by The Crystals.)

Mad Love won the Eisner for Best Single Story in 1994. It is currently available in several editions on Amazon, including a coloring book.

To be fair, Mad Love is a very good story: beautifully drawn, perfectly paced, gleefully creative, and genuinely funny in a way that still feels a little daring for a tie-in to a children’s cartoon. (It was adapted for the show five years later, with some of the violence and suggestive humor toned down.) I don’t think it glorifies an abusive relationship. I think it’s a bleak, darkly funny but ultimately sympathetic portrayal of how hard it is to break the cycle.

That said, it still left me feeling some kind of worried way when I got to the end and remembered how my friend had pitched it: “I am Harley Quinn.”

She wasn’t alone. I knew several girls in high school and college who related deeply to Mad Love, and to Harley in general. None of them, to my knowledge, were in abusive relationships. But the character still resonated.

And not just with teenage girls! Harley was popular enough that she was added to the main DCU in 1999 with the prestige format Batman: Harley Quinn; by 2001 she had her first solo series, which ran for 38 issues. In 2009 she teamed up with Poison Ivy and Catwoman for Gotham City Sirens; after the New 52 reboot in 2011 she became a key member of Suicide Squad and has remained so ever since. 2009 was also when she started appearing prominently in the Batman: Arkham series of video games. She has a major role in the Injustice games and tie-in comics as well, eventually joining the Justice League at the end of Injustice 2.

In 2013 Harley got her second solo series, co-written by Amanda Conner and Jimmy Palmiotti, which marked the first time Harley was written by a woman. It was replaced with her third solo series as of 2016’s Rebirth event, but she’s held down her own title without pause for six years with no signs of stopping. These series also begat several spinoff miniseries every year.

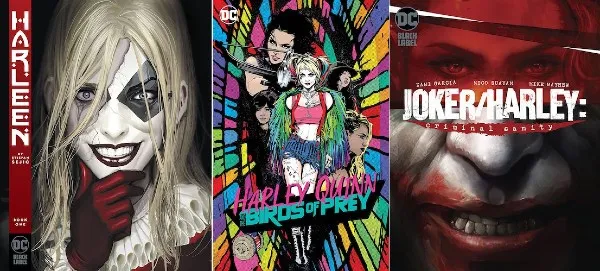

Harley has always been beloved, but her meteoric rise in the past five years is truly astonishing. The first issue of her Rebirth series sold 360K issues in a month, handily beating the runner up (All Star Batman #1, at 290K); DC says it shipped more copies than any other Rebirth title. In October of this year alone, Harley headlined an unprecedented five books: Harley Quinn, Harley Quinn and Poison Ivy, Birds of Prey, and Black Label’s Harleen and Joker/Harley: Criminal Sanity. Last month she starred in her own YA graphic novel, Harley Quinn: Breaking Glass. Only Superman and Batman can lay claim to that kind of omnipresence.

If you’re not familiar with it, Mad Love is a one-shot comic from 1994 by Paul Dini and Bruce Timm, set in the continuity of the then-running Batman: The Animated Series. It tells the origin story of Harley Quinn, the Joker’s bubbly Girl Friday, who had been introduced two years prior in the cartoon and quickly became a fan favorite. Harleen Quinzel, psychiatrist, gets a job at Arkham Asylum and finds herself falling for the Joker thanks to the sob stories he tells her. She embarks on a life of crime for him, and ultimately almost succeeds in killing Batman. Enraged that she’s come closer to his goal than he ever has, the Joker throws her through a window, landing her in the hospital wing of Arkham.

On the comic’s famous final page, Harley muses sadly on where her love for a violent killer has brought her. “He hit me…” she says. Then she notices the flower he left by her bedside, and brightens: “And it felt like a kiss!” (A reference to the disturbing 1962 song by the same name by The Crystals.)

Mad Love won the Eisner for Best Single Story in 1994. It is currently available in several editions on Amazon, including a coloring book.

To be fair, Mad Love is a very good story: beautifully drawn, perfectly paced, gleefully creative, and genuinely funny in a way that still feels a little daring for a tie-in to a children’s cartoon. (It was adapted for the show five years later, with some of the violence and suggestive humor toned down.) I don’t think it glorifies an abusive relationship. I think it’s a bleak, darkly funny but ultimately sympathetic portrayal of how hard it is to break the cycle.

That said, it still left me feeling some kind of worried way when I got to the end and remembered how my friend had pitched it: “I am Harley Quinn.”

She wasn’t alone. I knew several girls in high school and college who related deeply to Mad Love, and to Harley in general. None of them, to my knowledge, were in abusive relationships. But the character still resonated.

And not just with teenage girls! Harley was popular enough that she was added to the main DCU in 1999 with the prestige format Batman: Harley Quinn; by 2001 she had her first solo series, which ran for 38 issues. In 2009 she teamed up with Poison Ivy and Catwoman for Gotham City Sirens; after the New 52 reboot in 2011 she became a key member of Suicide Squad and has remained so ever since. 2009 was also when she started appearing prominently in the Batman: Arkham series of video games. She has a major role in the Injustice games and tie-in comics as well, eventually joining the Justice League at the end of Injustice 2.

In 2013 Harley got her second solo series, co-written by Amanda Conner and Jimmy Palmiotti, which marked the first time Harley was written by a woman. It was replaced with her third solo series as of 2016’s Rebirth event, but she’s held down her own title without pause for six years with no signs of stopping. These series also begat several spinoff miniseries every year.

Harley has always been beloved, but her meteoric rise in the past five years is truly astonishing. The first issue of her Rebirth series sold 360K issues in a month, handily beating the runner up (All Star Batman #1, at 290K); DC says it shipped more copies than any other Rebirth title. In October of this year alone, Harley headlined an unprecedented five books: Harley Quinn, Harley Quinn and Poison Ivy, Birds of Prey, and Black Label’s Harleen and Joker/Harley: Criminal Sanity. Last month she starred in her own YA graphic novel, Harley Quinn: Breaking Glass. Only Superman and Batman can lay claim to that kind of omnipresence.

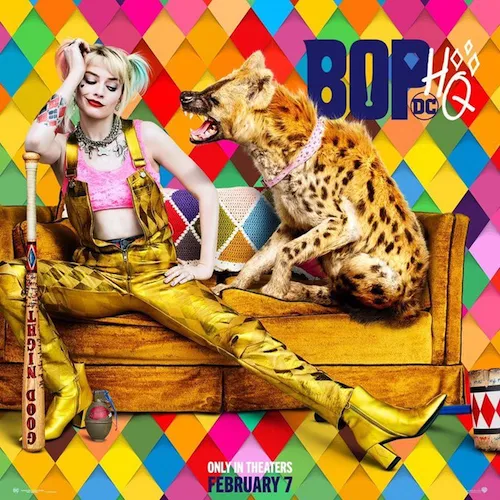

And it’s not just comics. Harley’s slated to star in her own eponymous animated show for adults on the DC Universe streaming platform later this year. She was a core member of the cast of the first iteration of the DC Super Hero Girls franchise, and remains in the revamped version, albeit with a reduced role. Oh yeah, and she’s the star of next February’s Birds of Prey (and the Fantabulous Emancipation of One Harley Quinn), starring and produced by Margot Robbie.

Basically, she’s DC’s Deadpool, complete with multimedia domination. Except…who is Harley Quinn? And when DC tells her story as many times as they can get away with, what kind of story are they telling?

Is Harley the victim of a twisted romance gone wrong, like we saw in Mad Love? Is she the distaff version of the Joker: a sadistic and unhinged murderer? Is her relationship with Poison Ivy about queer representation or the male gaze? Is she a Jewish, bisexual, mentally ill woman reclaiming her life from an abusive ex, or is she just a good opportunity for page after page of funny, vaguely kinky cheesecake? Or is she just a lovable old silly billy?

So far, DC’s answer to this question has been “all of the above.” The problem with that is that some of the versions of Harley they’re selling directly undermine the others.

And it’s not just comics. Harley’s slated to star in her own eponymous animated show for adults on the DC Universe streaming platform later this year. She was a core member of the cast of the first iteration of the DC Super Hero Girls franchise, and remains in the revamped version, albeit with a reduced role. Oh yeah, and she’s the star of next February’s Birds of Prey (and the Fantabulous Emancipation of One Harley Quinn), starring and produced by Margot Robbie.

Basically, she’s DC’s Deadpool, complete with multimedia domination. Except…who is Harley Quinn? And when DC tells her story as many times as they can get away with, what kind of story are they telling?

Is Harley the victim of a twisted romance gone wrong, like we saw in Mad Love? Is she the distaff version of the Joker: a sadistic and unhinged murderer? Is her relationship with Poison Ivy about queer representation or the male gaze? Is she a Jewish, bisexual, mentally ill woman reclaiming her life from an abusive ex, or is she just a good opportunity for page after page of funny, vaguely kinky cheesecake? Or is she just a lovable old silly billy?

So far, DC’s answer to this question has been “all of the above.” The problem with that is that some of the versions of Harley they’re selling directly undermine the others.

The bigger a character gets, the more flexible their characterization becomes. For example, Duke “the Signal” Thomas, the latest addition to the Batfamily, has only been around for five years, solely in Bat books, and with no multimedia appearances, so his personality is tied pretty firmly to those books. Batman, on the other hand, has been around for 80 years as a globally recognized icon, which means that his characterization can stretch from goofy Adam West to growly Christian Bale without breaking. He can be on a 5-year-old’s lunchbox and star in an ultra-violent video game, and the question becomes less “Which is the real Batman?” and more “Which items on this Batman tasting menu would you like to partake of?”

When approaching a Batman story, then, especially an out of continuity one, a creative team doesn’t necessarily need to worry about the minutiae of each prior appearance so much as what are the essential elements that make Batman Batman. So: parents murdered, dresses like a bat, doesn’t use guns and doesn’t kill, probably has a butler and at least one teenager hanging around. Break those rules, and fans will reject the story—see how unpopular Batman v Superman’s gun-toting, murderous Batman was. Follow them, and the rest is up to you.

A lot of these new Harley stories are out of continuity, which leaves the creative team free to disregard her history as much as they please. So what are the essential elements that make Harley Quinn Harley?

Can she be unequivocally heroic, or is antihero the best she can manage? Can she be unflinchingly sadistic, or does she require a heart of gold? Does she need to be a psychiatrist? Does she need a connection to Batman or Poison Ivy? Is her white skin the result of makeup or physical trauma?

Most importantly, does she need to have been victimized by the Joker to be Harley Quinn? And is she allowed to eventually escape that victimization?

DC hasn’t laid down any hard and fast answers so far. In Breaking Glass, Harley is a sunshiney kid with an unfortunate tendency towards violent mayhem; she is at worst slightly manipulated by the Joker but certainly not abused by him. In Joker/Harley: Criminal Sanity, she’s a forensic psychiatrist hunting down the Joker, an infamous serial killer, because he murdered her wife. In the original DC Super Hero Girls, she’s a well-meaning but wacky student at Super Hero High, without the slightest whiff of criminal intent; the Joker doesn’t appear to exist in that continuity. In Harleen, she’s a psychiatrist at Arkham wandering down the path we’re familiar with from Mad Love, falling into the Joker’s manipulative clutches. In a preview for the animated Harley Quinn, she gleefully murders a guy by shoving a bomb in his mouth. In the trailers for Birds of Prey, she’s a bubbly badass who is deliberately assembling a team of women in need of “emancipation” for some kind of zany caper.

The bigger a character gets, the more flexible their characterization becomes. For example, Duke “the Signal” Thomas, the latest addition to the Batfamily, has only been around for five years, solely in Bat books, and with no multimedia appearances, so his personality is tied pretty firmly to those books. Batman, on the other hand, has been around for 80 years as a globally recognized icon, which means that his characterization can stretch from goofy Adam West to growly Christian Bale without breaking. He can be on a 5-year-old’s lunchbox and star in an ultra-violent video game, and the question becomes less “Which is the real Batman?” and more “Which items on this Batman tasting menu would you like to partake of?”

When approaching a Batman story, then, especially an out of continuity one, a creative team doesn’t necessarily need to worry about the minutiae of each prior appearance so much as what are the essential elements that make Batman Batman. So: parents murdered, dresses like a bat, doesn’t use guns and doesn’t kill, probably has a butler and at least one teenager hanging around. Break those rules, and fans will reject the story—see how unpopular Batman v Superman’s gun-toting, murderous Batman was. Follow them, and the rest is up to you.

A lot of these new Harley stories are out of continuity, which leaves the creative team free to disregard her history as much as they please. So what are the essential elements that make Harley Quinn Harley?

Can she be unequivocally heroic, or is antihero the best she can manage? Can she be unflinchingly sadistic, or does she require a heart of gold? Does she need to be a psychiatrist? Does she need a connection to Batman or Poison Ivy? Is her white skin the result of makeup or physical trauma?

Most importantly, does she need to have been victimized by the Joker to be Harley Quinn? And is she allowed to eventually escape that victimization?

DC hasn’t laid down any hard and fast answers so far. In Breaking Glass, Harley is a sunshiney kid with an unfortunate tendency towards violent mayhem; she is at worst slightly manipulated by the Joker but certainly not abused by him. In Joker/Harley: Criminal Sanity, she’s a forensic psychiatrist hunting down the Joker, an infamous serial killer, because he murdered her wife. In the original DC Super Hero Girls, she’s a well-meaning but wacky student at Super Hero High, without the slightest whiff of criminal intent; the Joker doesn’t appear to exist in that continuity. In Harleen, she’s a psychiatrist at Arkham wandering down the path we’re familiar with from Mad Love, falling into the Joker’s manipulative clutches. In a preview for the animated Harley Quinn, she gleefully murders a guy by shoving a bomb in his mouth. In the trailers for Birds of Prey, she’s a bubbly badass who is deliberately assembling a team of women in need of “emancipation” for some kind of zany caper.

The problem is not necessarily the different levels of violence in these stories. Harley, like Batman, has grown to be a flexible character. She can investigate severed torsos in Joker/Harley and innocently break the timestream by pilfering a dinosaur egg in DC Super Hero Girls. That’s fine.

The problem is, DC wants to sell stories that rely on Harley triumphing over her victimization while simultaneously selling ones that revel in it.

For all the triumphant playfulness of Breaking Glass or Harley Quinn and Poison Ivy, which has a reunited Harley and Ivy contemplating fighting on the side of the angels, there’s a comic that painstakingly shows us exactly how the Joker broke Harley’s sanity (which is its own can of worms when it comes to sympathetic and non-sensationalist depictions of mental illness). Harleen is a beautiful book, but it’s a beautiful book that wallows in its heroine’s abuse. Writer/artist Stjepan Sejic describes it “a romance novel taken to its logical conclusion instead of its ideal one,” which is unintentionally sort of the perfect metaphor. In one sentence he dismisses an entire genre that revolves around the desires and triumphs of women as unrealistic, and frames his story about a woman’s suffering as “logical.” How can we believe in the stories where Harley escapes the Joker—or never falls prey to him at all—when the caretakers of the character think stories about women’s happiness are illogical?

Similarly, there’s a disconnect in how DC approaches Harley’s mental health. Harley was a star player in this year’s Heroes in Crisis, a miniseries that promised to explore mental illness and trauma with more sensitivity than the usual rock ‘em sock ‘em superhero story. The fact that it wound up actually being an incoherent whodunnit is beside the point. Like Harleen, it didn’t treat Harley’s mental illness as a punchline.

But it was only back in 2013—a mere blip in Comics Time—that DC sparked controversy with their “Break into comics with Harley Quinn!” contest, in which they asked fans to draw four pages from an upcoming Harley comic, each one depicting Harley cartoonishly attempting suicide. The fourth page was supposed to show Harley in the bath, naked, with a bunch of electrical appliances poised to fall in. The winner would have their art appear in the final issue. Plenty of fans pushed back against DC, uh, soliciting art of a naked, mentally ill woman attempting suicide, at which point DC changed the brief to “Harley riding a rocket through space” but also carefully explained that it was a joke, apparently under the impression that it’s okay to solicit sexualized depictions of suicide for fun and profit (and gatekeep out any artists uncomfortable with drawing this scenario) if it’s supposed to be funny.

(This incident, by the way, occurred several days before National Suicide Prevention Week.)

The above story also shows that DC can’t quite let go of Harley as Sex Object. Now, Harley’s always been heavily sexualized—she started out as a clown-themed pinup girl, after all—and plenty of the Harley cheesecake out there is perfectly charming, especially when drawn by Amanda Conner or Bruce Timm. But after the ten thousandth variant cover or statue of Harley looking dead behind the eyes with her bleached cleavage hanging out, one starts to suspect that Harley’s personality—and certainly Harley’s empowerment—is a distant second to Harley’s appeal as a weird but acceptable fetish.

To put it another way, it’s super weird that the same company sells these three items based on the same character:

The problem is not necessarily the different levels of violence in these stories. Harley, like Batman, has grown to be a flexible character. She can investigate severed torsos in Joker/Harley and innocently break the timestream by pilfering a dinosaur egg in DC Super Hero Girls. That’s fine.

The problem is, DC wants to sell stories that rely on Harley triumphing over her victimization while simultaneously selling ones that revel in it.

For all the triumphant playfulness of Breaking Glass or Harley Quinn and Poison Ivy, which has a reunited Harley and Ivy contemplating fighting on the side of the angels, there’s a comic that painstakingly shows us exactly how the Joker broke Harley’s sanity (which is its own can of worms when it comes to sympathetic and non-sensationalist depictions of mental illness). Harleen is a beautiful book, but it’s a beautiful book that wallows in its heroine’s abuse. Writer/artist Stjepan Sejic describes it “a romance novel taken to its logical conclusion instead of its ideal one,” which is unintentionally sort of the perfect metaphor. In one sentence he dismisses an entire genre that revolves around the desires and triumphs of women as unrealistic, and frames his story about a woman’s suffering as “logical.” How can we believe in the stories where Harley escapes the Joker—or never falls prey to him at all—when the caretakers of the character think stories about women’s happiness are illogical?

Similarly, there’s a disconnect in how DC approaches Harley’s mental health. Harley was a star player in this year’s Heroes in Crisis, a miniseries that promised to explore mental illness and trauma with more sensitivity than the usual rock ‘em sock ‘em superhero story. The fact that it wound up actually being an incoherent whodunnit is beside the point. Like Harleen, it didn’t treat Harley’s mental illness as a punchline.

But it was only back in 2013—a mere blip in Comics Time—that DC sparked controversy with their “Break into comics with Harley Quinn!” contest, in which they asked fans to draw four pages from an upcoming Harley comic, each one depicting Harley cartoonishly attempting suicide. The fourth page was supposed to show Harley in the bath, naked, with a bunch of electrical appliances poised to fall in. The winner would have their art appear in the final issue. Plenty of fans pushed back against DC, uh, soliciting art of a naked, mentally ill woman attempting suicide, at which point DC changed the brief to “Harley riding a rocket through space” but also carefully explained that it was a joke, apparently under the impression that it’s okay to solicit sexualized depictions of suicide for fun and profit (and gatekeep out any artists uncomfortable with drawing this scenario) if it’s supposed to be funny.

(This incident, by the way, occurred several days before National Suicide Prevention Week.)

The above story also shows that DC can’t quite let go of Harley as Sex Object. Now, Harley’s always been heavily sexualized—she started out as a clown-themed pinup girl, after all—and plenty of the Harley cheesecake out there is perfectly charming, especially when drawn by Amanda Conner or Bruce Timm. But after the ten thousandth variant cover or statue of Harley looking dead behind the eyes with her bleached cleavage hanging out, one starts to suspect that Harley’s personality—and certainly Harley’s empowerment—is a distant second to Harley’s appeal as a weird but acceptable fetish.

To put it another way, it’s super weird that the same company sells these three items based on the same character:

But then, to follow Harley’s career is to immerse yourself in cognitive dissonance. In September, I read Breaking Glass, in which a completely non-sexualized teen Harley fights gentrification. In October, I attended New York City Comic Con, where I saw many Harley cosplayers, but most memorably a girl who was about 12 or 13—the target age for Breaking Glass—in the full Suicide Squad movie costume: “Daddy’s Little Monster” shirt, hot pants, fishnets. She was leading around a grown man dressed as a cop or a prison guard—presumably her father—on a leash.

Now, whatever made this poor kid’s parents think that big ol’ yikes of a costume was a good idea is not DC’s fault. But the fact of the matter is that DC is selling Harley simultaneously as an all-ages pal, a cautionary tale, and a kink. Every time they tell a story that revels in her victimization, it makes the stories in which she triumphs over said victimization ring hollow. Every time they sexualize that victimization, it makes the fact that they’re pitching Harley to kids now just a little bit creepier.

Other marquee characters don’t have this problem, because while all DC characters have tragedy in their backgrounds, very few have Harley’s history of abuse, and certainly none of the big names: Wonder Woman, Supergirl, Lois Lane. The only character who comes close is Barbara Gordon, thanks to DC’s love affair with The Killing Joke and her assault by—of course—the Joker.

(Who, DC’s latest movie would like to remind you, is really a very sympathetic character.)

I’m not saying DC needs to excise the Joker from Harley’s past, or from future stories about her. Part of the reason that Harley resonates with so many people is because she’s an abuse survivor, because she’s mentally ill, because of her past with the Joker. I’m saying that DC needs to stop fetishizing it or pitching it as a dark romance. I’m saying that if DC wants to have a character with that kind of history in their stable, they need to approach her with a little more thought.

In other words, by all means, keep selling Mad Love. But do you have to sell it as a coloring book?

But then, to follow Harley’s career is to immerse yourself in cognitive dissonance. In September, I read Breaking Glass, in which a completely non-sexualized teen Harley fights gentrification. In October, I attended New York City Comic Con, where I saw many Harley cosplayers, but most memorably a girl who was about 12 or 13—the target age for Breaking Glass—in the full Suicide Squad movie costume: “Daddy’s Little Monster” shirt, hot pants, fishnets. She was leading around a grown man dressed as a cop or a prison guard—presumably her father—on a leash.

Now, whatever made this poor kid’s parents think that big ol’ yikes of a costume was a good idea is not DC’s fault. But the fact of the matter is that DC is selling Harley simultaneously as an all-ages pal, a cautionary tale, and a kink. Every time they tell a story that revels in her victimization, it makes the stories in which she triumphs over said victimization ring hollow. Every time they sexualize that victimization, it makes the fact that they’re pitching Harley to kids now just a little bit creepier.

Other marquee characters don’t have this problem, because while all DC characters have tragedy in their backgrounds, very few have Harley’s history of abuse, and certainly none of the big names: Wonder Woman, Supergirl, Lois Lane. The only character who comes close is Barbara Gordon, thanks to DC’s love affair with The Killing Joke and her assault by—of course—the Joker.

(Who, DC’s latest movie would like to remind you, is really a very sympathetic character.)

I’m not saying DC needs to excise the Joker from Harley’s past, or from future stories about her. Part of the reason that Harley resonates with so many people is because she’s an abuse survivor, because she’s mentally ill, because of her past with the Joker. I’m saying that DC needs to stop fetishizing it or pitching it as a dark romance. I’m saying that if DC wants to have a character with that kind of history in their stable, they need to approach her with a little more thought.

In other words, by all means, keep selling Mad Love. But do you have to sell it as a coloring book?

Harley’s profile is only going to grow in the next few years, thanks to the movie and TV show, and personally I welcome our new Jewish, bisexual, mentally ill abuse survivor overlord. Her world domination is a triumph for every teenage girl who read Mad Love 25 years ago and saw herself on the page. Yes, I still feel some kind of worried way when someone that young relates that hard to her story, but I’d rather they see themselves in Harley than never see themselves at all.

So before DC gleefully rolls around on their sacks of money like Harley and Ivy after they rob a bank, they should take a moment to remember to treat Harley Quinn with respect and sensitivity. Harley deserves it, and more importantly, so do all the girls she means so much to.

Harley’s profile is only going to grow in the next few years, thanks to the movie and TV show, and personally I welcome our new Jewish, bisexual, mentally ill abuse survivor overlord. Her world domination is a triumph for every teenage girl who read Mad Love 25 years ago and saw herself on the page. Yes, I still feel some kind of worried way when someone that young relates that hard to her story, but I’d rather they see themselves in Harley than never see themselves at all.

So before DC gleefully rolls around on their sacks of money like Harley and Ivy after they rob a bank, they should take a moment to remember to treat Harley Quinn with respect and sensitivity. Harley deserves it, and more importantly, so do all the girls she means so much to.

If you’re not familiar with it, Mad Love is a one-shot comic from 1994 by Paul Dini and Bruce Timm, set in the continuity of the then-running Batman: The Animated Series. It tells the origin story of Harley Quinn, the Joker’s bubbly Girl Friday, who had been introduced two years prior in the cartoon and quickly became a fan favorite. Harleen Quinzel, psychiatrist, gets a job at Arkham Asylum and finds herself falling for the Joker thanks to the sob stories he tells her. She embarks on a life of crime for him, and ultimately almost succeeds in killing Batman. Enraged that she’s come closer to his goal than he ever has, the Joker throws her through a window, landing her in the hospital wing of Arkham.

On the comic’s famous final page, Harley muses sadly on where her love for a violent killer has brought her. “He hit me…” she says. Then she notices the flower he left by her bedside, and brightens: “And it felt like a kiss!” (A reference to the disturbing 1962 song by the same name by The Crystals.)

Mad Love won the Eisner for Best Single Story in 1994. It is currently available in several editions on Amazon, including a coloring book.

To be fair, Mad Love is a very good story: beautifully drawn, perfectly paced, gleefully creative, and genuinely funny in a way that still feels a little daring for a tie-in to a children’s cartoon. (It was adapted for the show five years later, with some of the violence and suggestive humor toned down.) I don’t think it glorifies an abusive relationship. I think it’s a bleak, darkly funny but ultimately sympathetic portrayal of how hard it is to break the cycle.

That said, it still left me feeling some kind of worried way when I got to the end and remembered how my friend had pitched it: “I am Harley Quinn.”

She wasn’t alone. I knew several girls in high school and college who related deeply to Mad Love, and to Harley in general. None of them, to my knowledge, were in abusive relationships. But the character still resonated.

And not just with teenage girls! Harley was popular enough that she was added to the main DCU in 1999 with the prestige format Batman: Harley Quinn; by 2001 she had her first solo series, which ran for 38 issues. In 2009 she teamed up with Poison Ivy and Catwoman for Gotham City Sirens; after the New 52 reboot in 2011 she became a key member of Suicide Squad and has remained so ever since. 2009 was also when she started appearing prominently in the Batman: Arkham series of video games. She has a major role in the Injustice games and tie-in comics as well, eventually joining the Justice League at the end of Injustice 2.

In 2013 Harley got her second solo series, co-written by Amanda Conner and Jimmy Palmiotti, which marked the first time Harley was written by a woman. It was replaced with her third solo series as of 2016’s Rebirth event, but she’s held down her own title without pause for six years with no signs of stopping. These series also begat several spinoff miniseries every year.

Harley has always been beloved, but her meteoric rise in the past five years is truly astonishing. The first issue of her Rebirth series sold 360K issues in a month, handily beating the runner up (All Star Batman #1, at 290K); DC says it shipped more copies than any other Rebirth title. In October of this year alone, Harley headlined an unprecedented five books: Harley Quinn, Harley Quinn and Poison Ivy, Birds of Prey, and Black Label’s Harleen and Joker/Harley: Criminal Sanity. Last month she starred in her own YA graphic novel, Harley Quinn: Breaking Glass. Only Superman and Batman can lay claim to that kind of omnipresence.

If you’re not familiar with it, Mad Love is a one-shot comic from 1994 by Paul Dini and Bruce Timm, set in the continuity of the then-running Batman: The Animated Series. It tells the origin story of Harley Quinn, the Joker’s bubbly Girl Friday, who had been introduced two years prior in the cartoon and quickly became a fan favorite. Harleen Quinzel, psychiatrist, gets a job at Arkham Asylum and finds herself falling for the Joker thanks to the sob stories he tells her. She embarks on a life of crime for him, and ultimately almost succeeds in killing Batman. Enraged that she’s come closer to his goal than he ever has, the Joker throws her through a window, landing her in the hospital wing of Arkham.

On the comic’s famous final page, Harley muses sadly on where her love for a violent killer has brought her. “He hit me…” she says. Then she notices the flower he left by her bedside, and brightens: “And it felt like a kiss!” (A reference to the disturbing 1962 song by the same name by The Crystals.)

Mad Love won the Eisner for Best Single Story in 1994. It is currently available in several editions on Amazon, including a coloring book.

To be fair, Mad Love is a very good story: beautifully drawn, perfectly paced, gleefully creative, and genuinely funny in a way that still feels a little daring for a tie-in to a children’s cartoon. (It was adapted for the show five years later, with some of the violence and suggestive humor toned down.) I don’t think it glorifies an abusive relationship. I think it’s a bleak, darkly funny but ultimately sympathetic portrayal of how hard it is to break the cycle.

That said, it still left me feeling some kind of worried way when I got to the end and remembered how my friend had pitched it: “I am Harley Quinn.”

She wasn’t alone. I knew several girls in high school and college who related deeply to Mad Love, and to Harley in general. None of them, to my knowledge, were in abusive relationships. But the character still resonated.

And not just with teenage girls! Harley was popular enough that she was added to the main DCU in 1999 with the prestige format Batman: Harley Quinn; by 2001 she had her first solo series, which ran for 38 issues. In 2009 she teamed up with Poison Ivy and Catwoman for Gotham City Sirens; after the New 52 reboot in 2011 she became a key member of Suicide Squad and has remained so ever since. 2009 was also when she started appearing prominently in the Batman: Arkham series of video games. She has a major role in the Injustice games and tie-in comics as well, eventually joining the Justice League at the end of Injustice 2.

In 2013 Harley got her second solo series, co-written by Amanda Conner and Jimmy Palmiotti, which marked the first time Harley was written by a woman. It was replaced with her third solo series as of 2016’s Rebirth event, but she’s held down her own title without pause for six years with no signs of stopping. These series also begat several spinoff miniseries every year.

Harley has always been beloved, but her meteoric rise in the past five years is truly astonishing. The first issue of her Rebirth series sold 360K issues in a month, handily beating the runner up (All Star Batman #1, at 290K); DC says it shipped more copies than any other Rebirth title. In October of this year alone, Harley headlined an unprecedented five books: Harley Quinn, Harley Quinn and Poison Ivy, Birds of Prey, and Black Label’s Harleen and Joker/Harley: Criminal Sanity. Last month she starred in her own YA graphic novel, Harley Quinn: Breaking Glass. Only Superman and Batman can lay claim to that kind of omnipresence.

A month of Harleys (roughly).

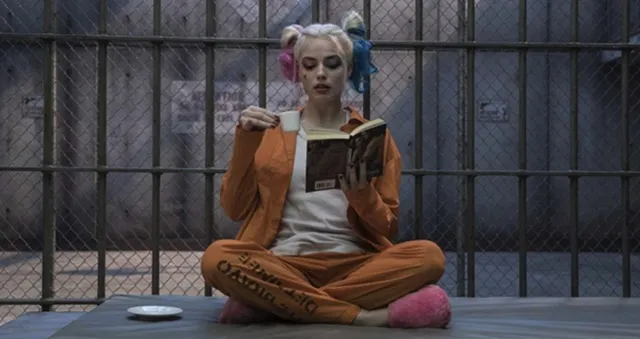

Margot Robbie in Birds of Prey

Harley and Joker in the upcoming animated show

But then, to follow Harley’s career is to immerse yourself in cognitive dissonance. In September, I read Breaking Glass, in which a completely non-sexualized teen Harley fights gentrification. In October, I attended New York City Comic Con, where I saw many Harley cosplayers, but most memorably a girl who was about 12 or 13—the target age for Breaking Glass—in the full Suicide Squad movie costume: “Daddy’s Little Monster” shirt, hot pants, fishnets. She was leading around a grown man dressed as a cop or a prison guard—presumably her father—on a leash.

Now, whatever made this poor kid’s parents think that big ol’ yikes of a costume was a good idea is not DC’s fault. But the fact of the matter is that DC is selling Harley simultaneously as an all-ages pal, a cautionary tale, and a kink. Every time they tell a story that revels in her victimization, it makes the stories in which she triumphs over said victimization ring hollow. Every time they sexualize that victimization, it makes the fact that they’re pitching Harley to kids now just a little bit creepier.

Other marquee characters don’t have this problem, because while all DC characters have tragedy in their backgrounds, very few have Harley’s history of abuse, and certainly none of the big names: Wonder Woman, Supergirl, Lois Lane. The only character who comes close is Barbara Gordon, thanks to DC’s love affair with The Killing Joke and her assault by—of course—the Joker.

(Who, DC’s latest movie would like to remind you, is really a very sympathetic character.)

I’m not saying DC needs to excise the Joker from Harley’s past, or from future stories about her. Part of the reason that Harley resonates with so many people is because she’s an abuse survivor, because she’s mentally ill, because of her past with the Joker. I’m saying that DC needs to stop fetishizing it or pitching it as a dark romance. I’m saying that if DC wants to have a character with that kind of history in their stable, they need to approach her with a little more thought.

In other words, by all means, keep selling Mad Love. But do you have to sell it as a coloring book?

But then, to follow Harley’s career is to immerse yourself in cognitive dissonance. In September, I read Breaking Glass, in which a completely non-sexualized teen Harley fights gentrification. In October, I attended New York City Comic Con, where I saw many Harley cosplayers, but most memorably a girl who was about 12 or 13—the target age for Breaking Glass—in the full Suicide Squad movie costume: “Daddy’s Little Monster” shirt, hot pants, fishnets. She was leading around a grown man dressed as a cop or a prison guard—presumably her father—on a leash.

Now, whatever made this poor kid’s parents think that big ol’ yikes of a costume was a good idea is not DC’s fault. But the fact of the matter is that DC is selling Harley simultaneously as an all-ages pal, a cautionary tale, and a kink. Every time they tell a story that revels in her victimization, it makes the stories in which she triumphs over said victimization ring hollow. Every time they sexualize that victimization, it makes the fact that they’re pitching Harley to kids now just a little bit creepier.

Other marquee characters don’t have this problem, because while all DC characters have tragedy in their backgrounds, very few have Harley’s history of abuse, and certainly none of the big names: Wonder Woman, Supergirl, Lois Lane. The only character who comes close is Barbara Gordon, thanks to DC’s love affair with The Killing Joke and her assault by—of course—the Joker.

(Who, DC’s latest movie would like to remind you, is really a very sympathetic character.)

I’m not saying DC needs to excise the Joker from Harley’s past, or from future stories about her. Part of the reason that Harley resonates with so many people is because she’s an abuse survivor, because she’s mentally ill, because of her past with the Joker. I’m saying that DC needs to stop fetishizing it or pitching it as a dark romance. I’m saying that if DC wants to have a character with that kind of history in their stable, they need to approach her with a little more thought.

In other words, by all means, keep selling Mad Love. But do you have to sell it as a coloring book?

Whose story is DC telling?