The True History of Human Flesh Books and Other Tales

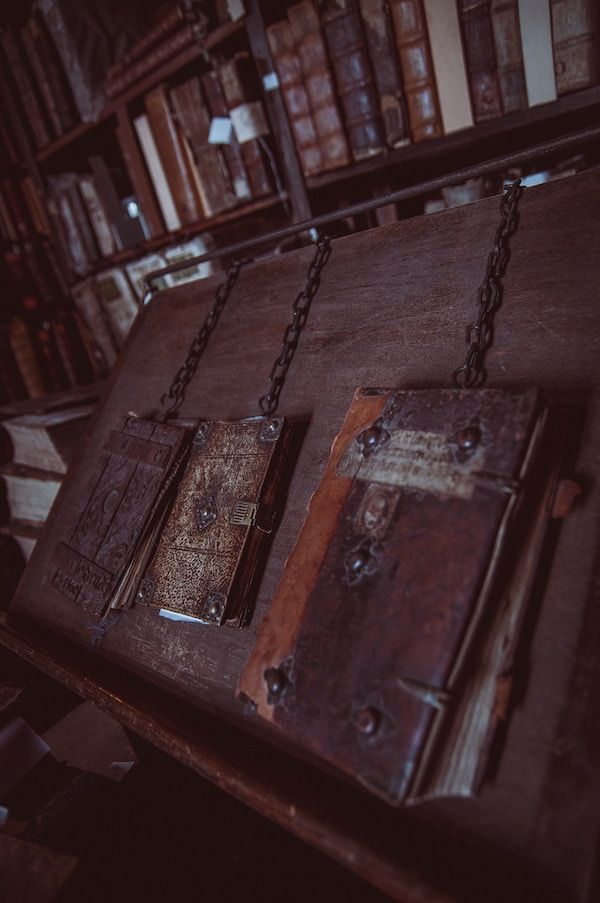

As we creep closer and closer to the best day of the year, Halloween, I decided it would be appropriate to consider the darker side of books: Anthropodermic bibliopegy. Or in plain English: Books bound in human flesh.

Behind the Grisly Practice

Researchers have found such books going back to the 16th century, but the heyday was the 19th century. Some of the texts were medical works while others were books about terrible crimes. Many times books are inscribes with a note that it is made from human flesh.

In an interview with Dr. Lindsey Fitzharris, a medical historian, at Vice in 2015, she identifies three principal reasons for the practice. The first was punishment; many criminals were executed and dissected and their skins were sometimes used to bind books about their crimes. She believes the practice petered out by the end of the 19th because of the changing views on capital punishment.

The second reason was for collectibility. She explains: “Whatever you collect, everybody kinda wants to have that really strange object. And so there were people who collected books bound in human skin.” Tattooed skin was a popular choice. In the Wellcome Trust in London, UK, she cites the example of a 16th century text about female virginity and reproductive organs and bound in the skin of an unknown woman that was carried around by a French anatomist.

The third reason was “memorialization.” She cites the example of the famous text The Highwayman: Narrative of the Life of James Allen alias George Walton (1837), at the Boston Athenaeum, that was bound in James Allen’s skin, as a gift to the man who foiled his crimes. The examples she gives for the first and third reasons are similar. However, the difference might be that criminals didn’t have a choice about the resting place of their skin, while Allen allegedly asked for his skin to be used for the book.

Other medical texts were bound in the skin of patients, such as Mary Lynch who died in an almshouse from several ailments in 1868. Dr. John Stockton Hough took some of her flesh, tanned it in a chamber pot with urine, and then used it for the spines of three books on women’s health.

However, there’s a lot of privilege wrapped up in all three reasons. Fitzharris notes the inbalance between the French anatomist who carried around the book that was made from a woman whose name is lost to time.

In an 2018 interview for Nautilus, Beth Lander, a librarian at the Mutter Museum of the College of Physicians of Philadelphia, noted in the case of medical books with human flesh: “the bindings may have reinforced the feelings of doctors as social superiors, especially to their poorer patients like Mary Lynch.”

Fact vs Fiction

However, there’s definitely a great deal of separating fact from fiction. Many stories of books bound in human flesh are just stories. Libraries in the U.S. (and elsewhere) have legends of these ghastly books, but many of the books turn out to be made from goat and other typical leathers.

For instance, the Newberry Library in Chicago is rumored to have a book with call sign Case Wing Y 4902 M27 made from human flesh, made popular by Audrey Niffenegger’s The Time Traveler’s Wife. According to a specific Q&A about the book, the Newberry explains: “It is the opinion of the conservation staff that the binding material is not human skin, but rather highly burnished goat.”

There’s now The Anthropodermic Book Project that tests books to confirm their human origins. As of May 2019, they report that 50 alleged books have been identified; 31 tested, 18 confirmed as human.

The Project has gotten around some of the challenges of testing the skin, notably that tanning skin destroys a lot of the DNA to test, according to Richard Hark, a chemistry professor at Juniata College in Huntingdon, Pennsylvania. Instead, the scientists use “Peptide mass fingerprinting” that allows them to “distinguish [the sample] among a large number of mammalian species, including human.”

However, the process has its limitations. Nautilus notes: “The method isn’t that precise—Hark and Kirby can’t use it to differentiate between, for example, human and gorilla collagen—but primate samples are sufficiently different from those of cows and sheep for the researchers to determine whether a binding is primate or ungulate in origin.”

Perhaps there are a bunch of allegedly human skin books that are really bound in primate skin? Someday we might develop that kind of specificity in testing.

Researchers do note there were limitations with using human skin. Fitzharris notes that “the skin is a lot thinner, so you can’t stretch it as well.” Unfortunately, she also notes that tanners didn’t keep many records, so the process has not been preserved for scholars. Perhaps that is for the best.

Regardless of who and why, these texts and their long tail legends will continue to hold a fascination for us in the book world.

Want More Ghastly Books?

Check out this list of psychological horror books or these horror books to get you more into the Halloween spirit.