Downright Demotic: Words Are Better Than Pictures

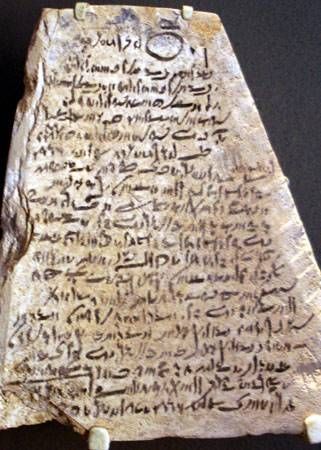

*Even, say, this one?

So I was heartened this week to read in the New York Times—which churns out about 140,000 words in an average edition, and twice that amount each Sunday—that even an ancient people famous for communicating through pictures knew words were what really mattered.

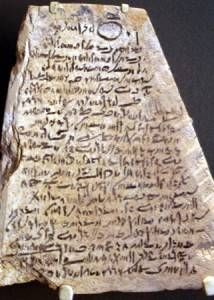

Despite the graffiti that made King Tut’s tomb famous, it turns out that hieroglyphs and other pictograms were not the primary form of written communication in use among the vast majority of Egyptians, who utilized words in script form, known as Demotic. “These were the words of love and family, the law and commerce, private letters and texts on science, religion and literature,” writes the Times’ John Noble Wilford. The language had probably been in use “from the beginning,” before eventually being replaced by Coptic and then Arabic. It was the Greeks who first identified it as Demotic, for “tongue of the demos,” the common people.

Of course, it had largely been Greek to most researchers, too, a scholarly dilemma that will be ameliorated by a new 2,000-page dictionary, 40 years in the making. (In case you’re curious, it’s all online.)

And it will give Egyptologists and fans of so-called “dead” languages (yes, that kind of Latin lover) new insight into ancient daily life that they could never get from, say, a thousand pictograms.

“What the Chicago Demotic Dictionary does is what the Oxford English Dictionary does,” said James P. Allen, an Egyptologist at Brown University. “It gives many samples of what words mean and the range and nuances of their meanings.”

It’s the versatility of words, their meanings, and their nuances that allow us to describe a picture in a thousand words—or two words, or two-hundred-thousand if we so desire.

In other words (har!), the old cliché is really a compliment.

By the way, for something of an entertaining “counterpoint,” check out illustrator Jason Novak’s visual explanation that all words—or, rather, letters—as we know them emerged from pictures.