What We Learned About Writing from Non-Writing Books

This content contains affiliate links. When you buy through these links, we may earn an affiliate commission.

October 20 is the National Day on Writing. It is a day that “celebrates the importance, joy, and evolution of writing through a tweetup, using the hashtag #WhyIWrite and events hosted by thousands of educators across the country.” I like participating in events like this, not only because I’m a writer and I enjoy trying new things for my craft, but because I love seeing how creative others get with it. I also really love to see the huge and diverse range of people who take part.

These kinds of events make me think not only about #WhyIWrite but it also about HOW I write. What influences have there been on my writing? What inspires me? What turns me off? What are the things I love to read? As many famous authors have said in some form or another, if you want to be a successful writer, you first have to be a reader. You cannot write without reading. Of course, that got me thinking about how the books I’ve read have influenced my writing, which in turn made me wonder about the books that I’ve read that aren’t writing books per se but that taught me about writing anyway.

So I asked my fellow contributors to talk to me about books that are not about writing but which have taught them about writing all the same. For example, maybe a character said something about writing that they’ve used as a rule of thumb ever since; maybe it was just the way a book was written that helped them develop their own writing style; maybe it was something else. In any case, these are books that are not actually about the craft of writing, but they taught us about writing all the same. Below are some comments Rioters shared about their favorite writing lessons from non-writing books.

For me, the beauty of Diaz’s writing is how he can take a description of the most everyday, mundane activity and somehow make it sound lyrical. His word choice is key. He doesn’t always go for the most obvious way to phrase something. Instead, he works his way around a description, creating an accessible but poetic metaphor that not only explains the situation- but puts his reader immediately in the action, feeling what the character is feeling. Reading The Brief and Wondrous Life of Oscar Wao started my own experiments with turns of phrase and gave me permission to be more playful with words.

—Elizabeth Allen

I don’t know if this one so much inspired my writing (although I do think it’s a brilliant, moving book) as it had a line that really resonated with me as a writer. “I have hated words and I have loved them, and I hope I have made them right.” I don’t think anything has ever better summed up my own experience as a writer–how I simultaneously love writing while also feeling like I’ve willingly taken on this insane, Sisyphean lifestyle.

Maybe not a lesson, but it’s definitely a good reminder that all writers are facing this strange and incomprehensible task of creating whole new worlds out of marks on a page. Writing can be such a solitary task at times that remembering others have faced, and are facing, the same struggles as you—loving the words and hating them—can be a real comfort. We’ve all been there.

—Rachel Brittain

“Snowman wakes before dawn. He lies unmoving, listening to the tide coming in, wave after wave sloshing over the various barricades, wish-wash, wish-wash, the rhythm of heartbeat. He would so like to believe he is still asleep.”

And so opens Oryx and Crake, the first in an apocalyptic trilogy by Margaret Atwood. The MaddAddam trilogy takes place in a future where science corporations have set up their own communities, separating themselves from the riffraff outside their gated homes and the world’s economic, social, and climate downfall. But then a virus tears through the world, leaving only a very few alive.

As a writer of speculative fiction, I return to this series again and again, particularly the first two. With Oryx and Crake, I look at how Atwood starts. What details she gives to signal this apocalyptic dystopia without infodumping, how she weaves the main character’s past and present together in a single narrative. With The Year of the Flood, and I look at how she uses voice, person, and tense to aid in character development. She switches between two characters in Flood, and with each character she changes person (she uses first and third) and tense (past and present) even though these narratives are occurring simultaneously! She also has many flashbacks. The entire series is such an amazing feat of writing technique. I may be doing myself a disservice by studying how she writes — since I can’t hope to ever reach her level — but I learn something about writing every time I read these books.

— Margaret Kingsbury

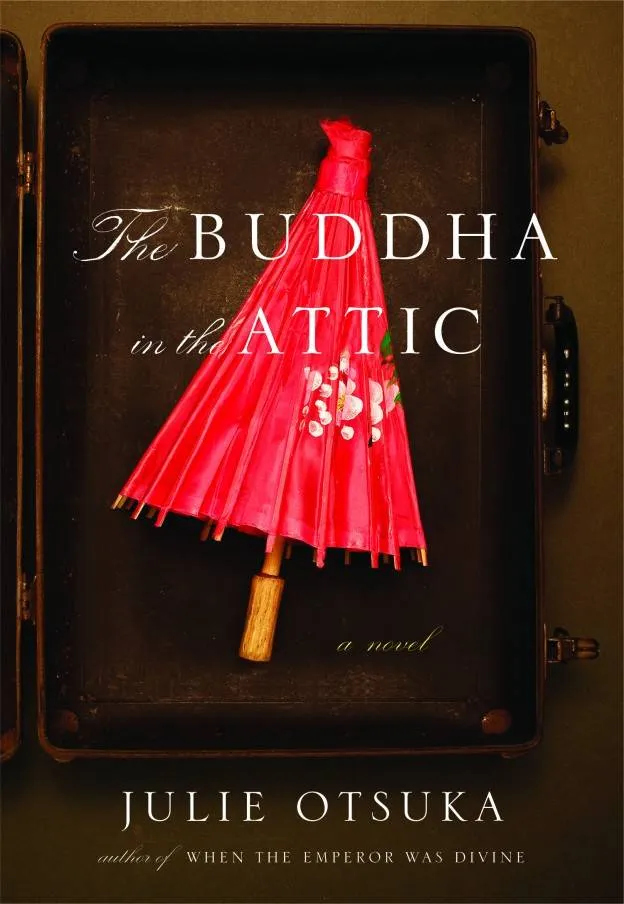

This book is a true gem. It taught me about the lyrical and emotional power of repetition — specifically anaphora, i.e. the repetition of a phrase at the beginning of sentences — and also about how the “we” narrator can work when used well. It led to me writing my favourite thing I’ve ever written, about a very different topic.

— Claire Handscombe

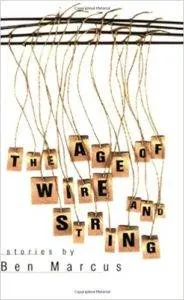

This is a bizarre book. Like, seriously, epicly weird. It’s also fantastic. Ben Marcus does this thing where he invents new ways to look at words. He gives them new meaning in a new world that is sort of like ours but not really because clouds are inside houses, and body parts are given the names of people, and water and birds and nature all act in unexpected ways. There’s no linear quality to this collection, really, except that there is – the linear plot is following the words to their definitions (confusing chapters in between stories provide abstract and odd definitions that don’t help with comprehension at all) and accepting the flow of words as plot. This book taught me, and continues to teach me, that I can experiment and play with language and allow it to tell its own story.

—Ilana Masad

What writing lessons have you learned from non-writing books? How will you participate in the National Day on Writing?