An Insomniac’s Anxiety: Why It Hurts to Read About Sleep

This content contains affiliate links. When you buy through these links, we may earn an affiliate commission.

When you have insomnia, people really want to be helpful. They suggest yoga, meditation, exercise, therapy. These suggestions can be hard for chronic insomniacs, as people often fail to understand how pervasive the disease is to our lives, how unavoidable.

But every once in a while, I would get someone who would assume my ignorance went even farther. “Your body really needs sleep. That’s really bad for your health,” they’d tell me, with a look of concern. As if I didn’t know. As if I wasn’t trying. No one seemed to realize that chronic insomnia was not “staying up too late,” not just being a night owl, not the busyness of life keeping me working ’til late. It was the inability to sleep, even when I was exhausted. They didn’t know that I would lay awake at night thinking of how much I’d hurt the next morning. That every time a friend had a cold I’d shrug, knowing I would soon have it too. That some days, when I called in to say I had a stomach bug, it was actually just that I hadn’t fallen asleep until 4 AM; that other days, I came into work with 4 hours or less and just tried to make it through with a steady caffeine supply.

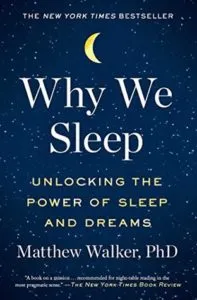

That feeling of being tired and frustrated was sharp and painful as I read Why We Sleep: Unlocking the Power of Sleep and Dreams by Matthew Walker. The tendency to close this book was strong, and a few times, I had turn away for a few hours or even days. The book is meant to be a call to action: it’s meant to tell the people who never get enough sleep that they have to start. But the thing is, I didn’t need to be called. I was already doing my best to get sleep, and failing anyway.

Reading this book, I read about how my years of insomnia could predispose me to cancer, Alzheimer’s, and so many more illnesses, injuries, and conditions. And I am angry at the doctor who told me in 6th grade, after I reported sleeping only 4–6 hours a night, that it was excess energy, and who then told me in 7th grade that it was hormones—ensuring that I wouldn’t bring it up to a doctor again for almost 15 more years.

I’m frustrated thinking of the sprained ankles, low race times, and low concentration that very well may have been influenced from years of insomnia and sleep deprivation, even as early therapists insisted my lack of sleep was caused entirely by my panic, and didn’t treat it as its own concern. I’m frustrated thinking of the flus, the strep throats, the colds, that have taken me out for weeks. And as someone who has been terrified all my life, even as a child, of losing their memory, realizing that sleep itself feeds so much more than I even realized into memory—and that some scientists believe it may be connected to the mystery of Alzheimer’s—hit me like a rock to the chest.

Luckily, at the encouragement of my therapist, I have finally gotten help. I’ve seen a sleep specialist, and my sleep is finally starting to improve with her methods of working against and adapting my body’s natural resistance to sleep. After seeing a psychiatrist, I am also on an SSRI for my anxiety and depression, and it has the lovely side effect of making me tired just before bed, and softening my anxious periods that had the potential to keep me up. I actually have the tools to even out my sleep. And that’s the reason I was able to finish this book—but it didn’t help me reading it.

That feeling of being tired and frustrated was sharp and painful as I read Why We Sleep: Unlocking the Power of Sleep and Dreams by Matthew Walker. The tendency to close this book was strong, and a few times, I had turn away for a few hours or even days. The book is meant to be a call to action: it’s meant to tell the people who never get enough sleep that they have to start. But the thing is, I didn’t need to be called. I was already doing my best to get sleep, and failing anyway.

Reading this book, I read about how my years of insomnia could predispose me to cancer, Alzheimer’s, and so many more illnesses, injuries, and conditions. And I am angry at the doctor who told me in 6th grade, after I reported sleeping only 4–6 hours a night, that it was excess energy, and who then told me in 7th grade that it was hormones—ensuring that I wouldn’t bring it up to a doctor again for almost 15 more years.

I’m frustrated thinking of the sprained ankles, low race times, and low concentration that very well may have been influenced from years of insomnia and sleep deprivation, even as early therapists insisted my lack of sleep was caused entirely by my panic, and didn’t treat it as its own concern. I’m frustrated thinking of the flus, the strep throats, the colds, that have taken me out for weeks. And as someone who has been terrified all my life, even as a child, of losing their memory, realizing that sleep itself feeds so much more than I even realized into memory—and that some scientists believe it may be connected to the mystery of Alzheimer’s—hit me like a rock to the chest.

Luckily, at the encouragement of my therapist, I have finally gotten help. I’ve seen a sleep specialist, and my sleep is finally starting to improve with her methods of working against and adapting my body’s natural resistance to sleep. After seeing a psychiatrist, I am also on an SSRI for my anxiety and depression, and it has the lovely side effect of making me tired just before bed, and softening my anxious periods that had the potential to keep me up. I actually have the tools to even out my sleep. And that’s the reason I was able to finish this book—but it didn’t help me reading it.

It’s strange to read books that are about your own suffering. It is harsh. Walker’s book is meant to tell people why they can’t actually survive on five hours of sleep, and he addresses everything from too-early school hours to the problems of the way society views sleep. I wasn’t surprised to find that I still found a lot of use out of this book, outside of the warnings it gave me about the damage my insomnia has likely already done.

But honestly, the strongest emotion after reading this book was justification. For years, I have been my own advocate, struggling through insomnia and trying desperately to convince doctors to take notice. My therapist was first to validate me; my sleep specialist second; and this book was third. Walker told me that I was right, all this time, to seek help, to worry about my sleep. And I’m glad I read it when I did.

I’m glad that I read this book now instead of before I met my sleep specialist. It’s a record of what I have worked so hard to escape. It’s a record of what I am saving myself from, instead of where I’ll be buried. A record of what damage I will hopefully avoid doing to my body from here on out. And most of all, a record of my persistence, of what I have always known: that my anxiety, my worry, my struggle, is valid.

It’s strange to read books that are about your own suffering. It is harsh. Walker’s book is meant to tell people why they can’t actually survive on five hours of sleep, and he addresses everything from too-early school hours to the problems of the way society views sleep. I wasn’t surprised to find that I still found a lot of use out of this book, outside of the warnings it gave me about the damage my insomnia has likely already done.

But honestly, the strongest emotion after reading this book was justification. For years, I have been my own advocate, struggling through insomnia and trying desperately to convince doctors to take notice. My therapist was first to validate me; my sleep specialist second; and this book was third. Walker told me that I was right, all this time, to seek help, to worry about my sleep. And I’m glad I read it when I did.

I’m glad that I read this book now instead of before I met my sleep specialist. It’s a record of what I have worked so hard to escape. It’s a record of what I am saving myself from, instead of where I’ll be buried. A record of what damage I will hopefully avoid doing to my body from here on out. And most of all, a record of my persistence, of what I have always known: that my anxiety, my worry, my struggle, is valid.

That feeling of being tired and frustrated was sharp and painful as I read Why We Sleep: Unlocking the Power of Sleep and Dreams by Matthew Walker. The tendency to close this book was strong, and a few times, I had turn away for a few hours or even days. The book is meant to be a call to action: it’s meant to tell the people who never get enough sleep that they have to start. But the thing is, I didn’t need to be called. I was already doing my best to get sleep, and failing anyway.

Reading this book, I read about how my years of insomnia could predispose me to cancer, Alzheimer’s, and so many more illnesses, injuries, and conditions. And I am angry at the doctor who told me in 6th grade, after I reported sleeping only 4–6 hours a night, that it was excess energy, and who then told me in 7th grade that it was hormones—ensuring that I wouldn’t bring it up to a doctor again for almost 15 more years.

I’m frustrated thinking of the sprained ankles, low race times, and low concentration that very well may have been influenced from years of insomnia and sleep deprivation, even as early therapists insisted my lack of sleep was caused entirely by my panic, and didn’t treat it as its own concern. I’m frustrated thinking of the flus, the strep throats, the colds, that have taken me out for weeks. And as someone who has been terrified all my life, even as a child, of losing their memory, realizing that sleep itself feeds so much more than I even realized into memory—and that some scientists believe it may be connected to the mystery of Alzheimer’s—hit me like a rock to the chest.

Luckily, at the encouragement of my therapist, I have finally gotten help. I’ve seen a sleep specialist, and my sleep is finally starting to improve with her methods of working against and adapting my body’s natural resistance to sleep. After seeing a psychiatrist, I am also on an SSRI for my anxiety and depression, and it has the lovely side effect of making me tired just before bed, and softening my anxious periods that had the potential to keep me up. I actually have the tools to even out my sleep. And that’s the reason I was able to finish this book—but it didn’t help me reading it.

That feeling of being tired and frustrated was sharp and painful as I read Why We Sleep: Unlocking the Power of Sleep and Dreams by Matthew Walker. The tendency to close this book was strong, and a few times, I had turn away for a few hours or even days. The book is meant to be a call to action: it’s meant to tell the people who never get enough sleep that they have to start. But the thing is, I didn’t need to be called. I was already doing my best to get sleep, and failing anyway.

Reading this book, I read about how my years of insomnia could predispose me to cancer, Alzheimer’s, and so many more illnesses, injuries, and conditions. And I am angry at the doctor who told me in 6th grade, after I reported sleeping only 4–6 hours a night, that it was excess energy, and who then told me in 7th grade that it was hormones—ensuring that I wouldn’t bring it up to a doctor again for almost 15 more years.

I’m frustrated thinking of the sprained ankles, low race times, and low concentration that very well may have been influenced from years of insomnia and sleep deprivation, even as early therapists insisted my lack of sleep was caused entirely by my panic, and didn’t treat it as its own concern. I’m frustrated thinking of the flus, the strep throats, the colds, that have taken me out for weeks. And as someone who has been terrified all my life, even as a child, of losing their memory, realizing that sleep itself feeds so much more than I even realized into memory—and that some scientists believe it may be connected to the mystery of Alzheimer’s—hit me like a rock to the chest.

Luckily, at the encouragement of my therapist, I have finally gotten help. I’ve seen a sleep specialist, and my sleep is finally starting to improve with her methods of working against and adapting my body’s natural resistance to sleep. After seeing a psychiatrist, I am also on an SSRI for my anxiety and depression, and it has the lovely side effect of making me tired just before bed, and softening my anxious periods that had the potential to keep me up. I actually have the tools to even out my sleep. And that’s the reason I was able to finish this book—but it didn’t help me reading it.

It’s strange to read books that are about your own suffering. It is harsh. Walker’s book is meant to tell people why they can’t actually survive on five hours of sleep, and he addresses everything from too-early school hours to the problems of the way society views sleep. I wasn’t surprised to find that I still found a lot of use out of this book, outside of the warnings it gave me about the damage my insomnia has likely already done.

But honestly, the strongest emotion after reading this book was justification. For years, I have been my own advocate, struggling through insomnia and trying desperately to convince doctors to take notice. My therapist was first to validate me; my sleep specialist second; and this book was third. Walker told me that I was right, all this time, to seek help, to worry about my sleep. And I’m glad I read it when I did.

I’m glad that I read this book now instead of before I met my sleep specialist. It’s a record of what I have worked so hard to escape. It’s a record of what I am saving myself from, instead of where I’ll be buried. A record of what damage I will hopefully avoid doing to my body from here on out. And most of all, a record of my persistence, of what I have always known: that my anxiety, my worry, my struggle, is valid.

It’s strange to read books that are about your own suffering. It is harsh. Walker’s book is meant to tell people why they can’t actually survive on five hours of sleep, and he addresses everything from too-early school hours to the problems of the way society views sleep. I wasn’t surprised to find that I still found a lot of use out of this book, outside of the warnings it gave me about the damage my insomnia has likely already done.

But honestly, the strongest emotion after reading this book was justification. For years, I have been my own advocate, struggling through insomnia and trying desperately to convince doctors to take notice. My therapist was first to validate me; my sleep specialist second; and this book was third. Walker told me that I was right, all this time, to seek help, to worry about my sleep. And I’m glad I read it when I did.

I’m glad that I read this book now instead of before I met my sleep specialist. It’s a record of what I have worked so hard to escape. It’s a record of what I am saving myself from, instead of where I’ll be buried. A record of what damage I will hopefully avoid doing to my body from here on out. And most of all, a record of my persistence, of what I have always known: that my anxiety, my worry, my struggle, is valid.