What a Lost Book Taught Me about Parenting, Airplanes, and Passion

This content contains affiliate links. When you buy through these links, we may earn an affiliate commission.

Despite the fact that my dad, stepmother, and son are all pilots, and I can’t even recall a time when everything aviation wasn’t a part of my life, I like ground travel. And I much prefer to move at a walking pace. Or bicycle speed, if I’m in a hurry. Shoot, I don’t even own a car.

But this past week has been all about the airplanes. I traveled (by air) to see my son’s flight team at the National Intercollegiate Flying Association regional competition at the U.S. Air Force Academy in Colorado Springs.

(Just typing all those airplane-y, up-in-the-sky words gives me the vapors.)

My stepmother lives in the Springs, so I stayed with her, and she tried, from the bleachers, to explain some of the lingo to me. In one ear, out the other. What my mind held onto was the cutting of the engines on approach during one event, which…hello? That seems a bad idea indeed.

But the whole experience was fascinating, a visit to a world that is utterly foreign to me.

And then, home again, I happened on Mark Vanhoenacker’s lovely New York Times essay about the 747, which will be retired in the United States this year.

Nearly all of my earliest memories center around events in airports or airplanes, especially the 747. Once, when I was small, I left my favorite doll at flight ops, and didn’t realize the loss until we were out at the gate. We had time to fetch her, so my dad and I hopped back on the crew bus to go back. It was dark and cold, and moving about outside at night in that strange place was terrifying.

As we approached the low building, my dad said, “Look, Nicole! Look!”

He was laughing. Laughing! This was serious business. What if someone had taken her?

And then I saw. Someone had propped the doll in the window, waving. Tied around the wrist of my doll’s other little plastic hand was one of those travel goodie packs. Back in those olden days, children were given little bags of crayons and tiny coloring books, sometimes a toy or candy, and, always, tiny plastic wings to wear. Just like a real pilot. (Or just like a stewardess, if you were a girl. [*cough*] I mean, we’re talking a very long time ago, before we used the term “flight attendant,” when, can you believe it? Everyone was fed on airplanes, actual meals, and we didn’t have to pay for checked baggage.)

I have a specific memory of tying my doll into my coat belt so I could use two hands while climbing the spiral stairs to the lounge of the 747. The stewardess was sympathetic about our ordeal, and helped me strap the doll into her own seatbelt, and found an extra set of wings for the doll.

This left-behind-doll incident must have happened when I was very young. Because I learned pretty quickly that the best part of travel, especially flying standby, which takes forever and a damn day and means so much waiting you cannot imagine—the best part is reading time. Once I began to read, the dolls were relieved of travel-pal duty.

Early on, when the 747s were still new, I remember being allowed on a few occasions to go upstairs, which was a strange and magical place. Family legend has it that once, buying a drink at the lounge bar, my father heard Richard Burton exclaim to his companion, My God! She looks just like Elizabeth! I don’t know if this happened, but it is true that my mother bore an uncanny resemblance to Elizabeth Taylor.

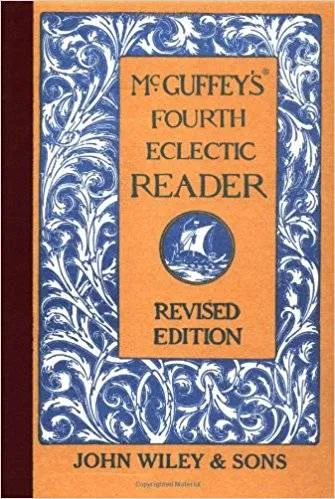

And it was in the upstairs lounge of a 747 that I left behind a book as precious to me as that doll. We had been to visit my great Aunt Ethel and Uncle Harmon in Ohio. It must have been summer, because that was the time I learned that strawberries grow on plants, close to the ground. My Aunt Ethel, who was a parsimonious, manipulative, and unkind woman, in a moment of uncharacteristic generosity, had given me a worn old copy of McGuffey’s Fourth Eclectic Reader.

On second thought, maybe this was a passive-aggressive move, and she thought I needed more reading instruction. Who knows! Whatever the case, I’d never seen anything like that book, and I was fascinated. This was the early 1970s, and children’s books were, in my very humble opinion, absolutely hideous. I loved the font in that old reader, the illustrations, the scent and silky smooth feel of the pages.

At any rate, on the flight home, I was allowed to go play upstairs on the plane. I was getting old enough that I wasn’t interested much in the goodie pack. And I had my own crayons, in a plastic box that made a satisfying sound as the crayon scented air whooshed out when you closed it.

I didn’t realize until we were home that the box and the book were not with us. It had been my mother’s book. She was upset.

As an adult, over the years, I kept my eyes peeled. I’m not close to my mother, but I had a bee in my bonnet to replace that slim little volume. I would peek at the McGuffey’s readers whenever I happened across them in used bookshops or antique stores or garage sales. It was a long while before I found the very same edition, the book I had lost. Not a reprint or facsimile copy, either.

And it was in the upstairs lounge of a 747 that I left behind a book as precious to me as that doll. We had been to visit my great Aunt Ethel and Uncle Harmon in Ohio. It must have been summer, because that was the time I learned that strawberries grow on plants, close to the ground. My Aunt Ethel, who was a parsimonious, manipulative, and unkind woman, in a moment of uncharacteristic generosity, had given me a worn old copy of McGuffey’s Fourth Eclectic Reader.

On second thought, maybe this was a passive-aggressive move, and she thought I needed more reading instruction. Who knows! Whatever the case, I’d never seen anything like that book, and I was fascinated. This was the early 1970s, and children’s books were, in my very humble opinion, absolutely hideous. I loved the font in that old reader, the illustrations, the scent and silky smooth feel of the pages.

At any rate, on the flight home, I was allowed to go play upstairs on the plane. I was getting old enough that I wasn’t interested much in the goodie pack. And I had my own crayons, in a plastic box that made a satisfying sound as the crayon scented air whooshed out when you closed it.

I didn’t realize until we were home that the box and the book were not with us. It had been my mother’s book. She was upset.

As an adult, over the years, I kept my eyes peeled. I’m not close to my mother, but I had a bee in my bonnet to replace that slim little volume. I would peek at the McGuffey’s readers whenever I happened across them in used bookshops or antique stores or garage sales. It was a long while before I found the very same edition, the book I had lost. Not a reprint or facsimile copy, either.

I felt such a satisfaction when I gave it to her.

As she opened the wrapping her face remained impassive. No sign of recognition.

I waited. Nothing. She had forgotten. Even when I told her the story, she showed not the tiniest hint of recollection.

!!!

What was curious to me was that even the story of the lost book and the story of my decades long search wasn’t compelling to my mother. She wasn’t even able to fake an interest. She’d lost the memory of the book itself, and the reunion was meaningless to her, and, sadly, so was the gesture, the gift.

Now, I might not be able to feel the thrill of flight, myself, but I take delight in my son’s passion. When we’re out and about and a plane roars over, his face turns upward. I generally pause in my blathering—he’s not much of a talker, but he’s a good listener—because I know he is thinking about that aircraft. And I know that he will likely be able to name all sorts of details about the machine, whereas I see only a blur in the sky making noise. I can and absolutely do admire that kind of attention, the ability to see and name with specificity. I resonate with the passion itself, even if the object of desire isn’t something that stirs me.

I suppose what I loved about Mark Vanhoenacker’s piece was that he is on fire not just about the plane itself, but all the stories it inspires. Of course I’m also sorry that the 747 will retire, and that future generations will not get to see and enjoy the thrill of that plane, that my son will not get to fly the plane his grandfather loved to fly. But we have the stories. So does Vanhoenacker, and he is keen to share, to “marvel” together. He ends with this invitation:

“Perhaps you’ll tell me about the first time you ever saw a 747, or flew on one, and together we’ll marvel at how it towers above us even at its lowest altitude, even as it rests on the world.”

Marveling, especially from below, down here on terra firma—now that, I can do.

I felt such a satisfaction when I gave it to her.

As she opened the wrapping her face remained impassive. No sign of recognition.

I waited. Nothing. She had forgotten. Even when I told her the story, she showed not the tiniest hint of recollection.

!!!

What was curious to me was that even the story of the lost book and the story of my decades long search wasn’t compelling to my mother. She wasn’t even able to fake an interest. She’d lost the memory of the book itself, and the reunion was meaningless to her, and, sadly, so was the gesture, the gift.

Now, I might not be able to feel the thrill of flight, myself, but I take delight in my son’s passion. When we’re out and about and a plane roars over, his face turns upward. I generally pause in my blathering—he’s not much of a talker, but he’s a good listener—because I know he is thinking about that aircraft. And I know that he will likely be able to name all sorts of details about the machine, whereas I see only a blur in the sky making noise. I can and absolutely do admire that kind of attention, the ability to see and name with specificity. I resonate with the passion itself, even if the object of desire isn’t something that stirs me.

I suppose what I loved about Mark Vanhoenacker’s piece was that he is on fire not just about the plane itself, but all the stories it inspires. Of course I’m also sorry that the 747 will retire, and that future generations will not get to see and enjoy the thrill of that plane, that my son will not get to fly the plane his grandfather loved to fly. But we have the stories. So does Vanhoenacker, and he is keen to share, to “marvel” together. He ends with this invitation:

“Perhaps you’ll tell me about the first time you ever saw a 747, or flew on one, and together we’ll marvel at how it towers above us even at its lowest altitude, even as it rests on the world.”

Marveling, especially from below, down here on terra firma—now that, I can do.

And it was in the upstairs lounge of a 747 that I left behind a book as precious to me as that doll. We had been to visit my great Aunt Ethel and Uncle Harmon in Ohio. It must have been summer, because that was the time I learned that strawberries grow on plants, close to the ground. My Aunt Ethel, who was a parsimonious, manipulative, and unkind woman, in a moment of uncharacteristic generosity, had given me a worn old copy of McGuffey’s Fourth Eclectic Reader.

On second thought, maybe this was a passive-aggressive move, and she thought I needed more reading instruction. Who knows! Whatever the case, I’d never seen anything like that book, and I was fascinated. This was the early 1970s, and children’s books were, in my very humble opinion, absolutely hideous. I loved the font in that old reader, the illustrations, the scent and silky smooth feel of the pages.

At any rate, on the flight home, I was allowed to go play upstairs on the plane. I was getting old enough that I wasn’t interested much in the goodie pack. And I had my own crayons, in a plastic box that made a satisfying sound as the crayon scented air whooshed out when you closed it.

I didn’t realize until we were home that the box and the book were not with us. It had been my mother’s book. She was upset.

As an adult, over the years, I kept my eyes peeled. I’m not close to my mother, but I had a bee in my bonnet to replace that slim little volume. I would peek at the McGuffey’s readers whenever I happened across them in used bookshops or antique stores or garage sales. It was a long while before I found the very same edition, the book I had lost. Not a reprint or facsimile copy, either.

And it was in the upstairs lounge of a 747 that I left behind a book as precious to me as that doll. We had been to visit my great Aunt Ethel and Uncle Harmon in Ohio. It must have been summer, because that was the time I learned that strawberries grow on plants, close to the ground. My Aunt Ethel, who was a parsimonious, manipulative, and unkind woman, in a moment of uncharacteristic generosity, had given me a worn old copy of McGuffey’s Fourth Eclectic Reader.

On second thought, maybe this was a passive-aggressive move, and she thought I needed more reading instruction. Who knows! Whatever the case, I’d never seen anything like that book, and I was fascinated. This was the early 1970s, and children’s books were, in my very humble opinion, absolutely hideous. I loved the font in that old reader, the illustrations, the scent and silky smooth feel of the pages.

At any rate, on the flight home, I was allowed to go play upstairs on the plane. I was getting old enough that I wasn’t interested much in the goodie pack. And I had my own crayons, in a plastic box that made a satisfying sound as the crayon scented air whooshed out when you closed it.

I didn’t realize until we were home that the box and the book were not with us. It had been my mother’s book. She was upset.

As an adult, over the years, I kept my eyes peeled. I’m not close to my mother, but I had a bee in my bonnet to replace that slim little volume. I would peek at the McGuffey’s readers whenever I happened across them in used bookshops or antique stores or garage sales. It was a long while before I found the very same edition, the book I had lost. Not a reprint or facsimile copy, either.

Some of the readers I accidentally bought when I was looking to replace the one I’d lost.