Reading Pathways: Ursula K. Le Guin

This content contains affiliate links. When you buy through these links, we may earn an affiliate commission.

Despite being an avid SFF reader since childhood, I was in my late 20s before I picked up a book by Ursula K. Le Guin, and thus discovered the person who would become one of my favorite authors of all time. It happened when one of the managers at the bookstore where I work casually mentioned he’d finished A Wizard of Earthsea and wondered which one of hers I’d recommend he read next, assuming I was already well versed in her oeuvre. The thing is, because I work at a used bookstore, I’d collected dozens of her books meaning to read them, and just not gotten around to it. I decided that night I would read one.

But instead of reading A Wizard of Earthsea first, I found myself drawn to The Left Hand of Darkness. It was gorgeous. Once I finished it, I immediately picked up The Dispossessed, and that’s the book that sealed the deal for me. I was hooked.

The way Le Guin combines philosophy, anthropology, and a depth of compassion is completely unique to her writing. She brings this combination to everything she’s written, and that’s an epic amount in many different genres. And I’ve fallen hard for them all, from her poetry to her middle grade to her religious translations. One of the reasons I think it took me SO LONG to read her is because she’s written an intimidating amount of books. But please, wait no longer. She will change your reading life. Here are my recommendations for where to start.

I sincerely hope you’ve never watched the less than mediocre TV adaptation or the Studio Ghibli film, one of the rare misses for the studio. When I pitch this book to people, I tell them it’s a magic school before Harry Potter, but that description does a disservice to the wisdom and philosophical contemplations in this slim novel. The book uses fantasy and word magic as a means of exploring identity and self-definition. It’s also a rare fantasy novel of the time (1968) to feature a brown protagonist.

or

Le Guin wrote more science fiction novels than any other genre. In her introduction to this book, she says:

“All fiction is metaphor. Science fiction is metaphor. What sets it apart from older forms of fiction seems to be its use of new metaphors…A metaphor for what?…that the truth is a matter of the imagination.”

Published a year after A Wizard of Earthsea, The Left Hand of Darkness won both the Hugo and Nebula awards. It ponders similar questions of identity but in an utterly different way. In Winter, or Gethen, Gethenians can change their gender. The single human emissary to the planet, Genly, struggles with understanding the Gethenians: their gender, their culture, their attitudes. It’s a fascinating novel and love story.

If you started with A Wizard of Earthsea, then continue on with the series! The Tombs of Atuan is my favorite of the first three.

or

I have three of her books I consider my favorites, and this is one of the three. It made me reconsider socialism. Its subtitle is “An Ambiguous Utopia,” a theme set up from beginning to end. Can there be an ideal civilization? In theory, Anarres should be it. A colony of the capitalist mother planet Urras, the people of Anarres set out to create a truly equitable society. But it comes at a cost. Shevek, a genius physicist, feels that cost in his lack of ability to truly dedicate himself to his science. And he has questions about the nature of civilization and humanity that burn to be answered.

Her poems are completely realistic and completely beautiful. She once wrote in an essay that she found herself unable to write fantasy or science fiction in her poetry. Instead, her poems are odes to nature, most similar to Mary Oliver’s, though less like prayers and more like character drawings. They’re very accessible, and I consider her books of poetry some of the best in my collection. I wish more people read them.

or

This epic volume collects many of Le Guin’s best short stories. I particularly recommend reading “The Ones Who Walk Away from Omelas” and “Buffalo Gals, Won’t You Come Out Tonight.”

or

Lavinia retells The Aeneid from Lavinia’s perspective. While Lavinia is barely mentioned in the epic (like in many ancient epics), Virgil says she’s the reason the war ended. Now we get her story, in this fantastic meditation that reminds me of Till We Have Faces by C.S. Lewis.

Another one of my three favorites, Always Coming Home is an anthropological text of the fictional Kesh people, who live along the California coast. It takes place an indeterminate amount of time after an apocalypse scenario that has eliminated a lot of technology. The narrator is an anthropologist from the East observing the Kesh, and collecting their traditions, songs, and folktales into this text. She also has Stone Telling, a Kesh woman, tell her autobiography, which is interspersed throughout. There is no other book remotely similar to this one. It’s difficult to sink into at first, but unforgettable in the end. She and composer Todd Barton even created an accompanying soundtrack!

or

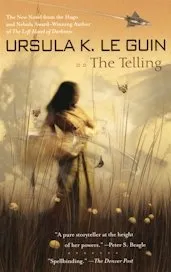

This is one of her more dense and lyrical novels, and the final of my top three books. Sutty is an anthropologist who crosses space to study the intentionally illiterate Aka society. They were once a literate culture but found literacy to be detrimental to society, so anything textual is banned. While it may sound similar to Always Coming Home, it’s written as a novel and is very different. Sutty herself comes from Terra, a future Earth racked with religious extremism. Being among the oppressive Aka regime sends her reeling into her past traumas of religious suppression. This book is masterfully written, with echos of Daoism, a religion and philosophy Le Guin greatly admired (she even translated the Tao Te Ching).

As a note, many of her science fiction novels are listed as Hainish #X. You can and should read these in any order. They are not meant to be read sequentially and do not have the same characters or plots. If it makes you feel better, Le Guin herself would prefer you not to give any heed to the numbers:

“People write me nice letters asking what order they ought to read my science fiction books in — the ones that are called the Hainish or Ekumen cycle or saga or something. The thing is, they aren’t a cycle or a saga. They do not form a coherent history. There are some clear connections among them, yes, but also some extremely murky ones. And some great discontinuities…”

I hope she makes as big an impact on your reading life as she has mine! Also check out this list of her books by what age you should read them (um, any age btw).

A documentary about her life, Worlds of Ursula K. Le Guin, airs on PBS Friday, August 2.