The Rocky Balboa School of Writing: Alex George

When I first heard the story behind the publication of Twilight, (Stephenie Meyer had a dream about vampires, wrote it down and used a lot of adverbs, and three months after her 130,000 word dream had a book deal), I threw up in my mouth a little bit. This has become a glorified story, and I don’t like what it’s glorifying.

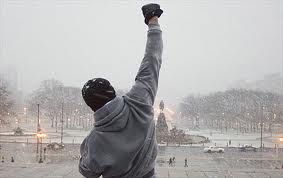

So I want to do some “Rocky Balboa School of Writing” interviews with authors who have faced a long, long road to publication. These are men and women who have jogged up and down the proverbial steps of the Philadelphia Art Museum more times than they can count. These authors have worked their asses off, and that hard work is now paying off like triple cherries lining up in a Vegas slot machine. I want these to be the stories that get the glory.

We’re starting with Alex George, whose novel A Good American just came out February 7th, 2012, and is already garnering huge buzz, including some Oprah magazine love.

____________________________

Kit Steinkellner: So to start, I’d love it if you could lay out a mini-timeline of your road to publication. You know, how long the initial draft took, and the approximate amount of time each step took along the way. Then we can dig into specifics.

We had recently moved to Missouri from England, and I had started – and abandoned – two other novels. One was about a concert pianist with nine fingers who lived in Occupied France during WWII, the other was about the Algerian War of Independence, which was a subject that I – but apparently only I – found fascinating. Anyway, neither of those ideas was going anywhere, and so I began this book instead.

When I began I had just requalified as an attorney. I had to take the Missouri bar exam which required six months of full-time study, and I hadn’t written at all during that time. That meant it was a relief to get back to writing again. At the same time as I began, I was looking for a job, but nobody wanted to hire a lawyer with a funny accent around here, so I had plenty of time to work on the book.

Finally, in 2005, I became a partner in a law firm in Jefferson City – about 45 minutes away from where I live – and things got more complicated. At that point I went back to the old routine that I had employed when I lived in London, which was to get up early and write each morning before going off to work. Only rather than get up at 6, I got up at 5.

KS: Let’s talk about that for a quick second: HOW DID YOU DO THAT? Did you go to bed right after dinner? Did you subsist entirely on caffeinated beverages? Are you one of the X-Men?

AG: I used to go to bed at about 10:30. After a while your body gets used to the early starts. I would get up, drink some coffee, and be ready to go. Once I’m up, I am ready to write, and since it’s early my brain is relatively unclogged up by the usual baggage that can accumulate over the course of a day. I tried to write in the evenings and was always too tired or distracted by whatever had gone on that day.

KS: I’ll let you get back to your timeline.

AG: So I kept on with the early mornings, and about five years later, I had a book! I gave it to a few close friends to read, and they seemed to like it. I sent it to my agent in London, Bruce Hunter. And he liked it too. He then sent it to my New York agent, Emma Sweeney. And she liked it too. We decided to do simultaneous submissions in London and New York. I settled back to watch the bidding wars escalate.

The first response we got back was from Amy Einhorn. She rejected the manuscript, saying “This is one of those rejections that kind of breaks your heart.” She loved the first two-thirds of the novel but felt that the last part really let it down. She felt that the problems were too big to be overcome in the editorial process, but said that she would welcome the chance to look at it again if I ever rewrote it.

On we went. There followed a series of glowing emails from all the major publishers. None of whom wanted to publish it.

It was a tough time. The downside of the whole 5 a.m. thing and living in a different time zone to my agent is that these rejection emails would be waiting for me in my inbox each morning. It was like taking a punch in the gut first thing in the morning.

A few months in, I called a halt to the submissions process. Clearly there was something wrong with the book as it was. So then I spent six months doing a massive rewrite. And while I wasn’t thinking only of Amy’s comments, what she had said made an awful lot of sense.

KS: And is it possible to talk about what some of those thoughts were?

SPOILER ALERT!

(Well, semi-spoiler alert, because we’re going to be talking about a bunch of things that no longer exist in the novel.)

When he returned home from fighting he began a hermit’s existence in a small house in the woods in the bootheel of Missouri. The final bit of the story was all about that, and how Kames, the narrator, tried to bring him back into the family fold. Anyway, that all went.

END SPOILER ALERT!

AG: So… the manuscript goes back to Amy Einhorn, who promises to read it. And we wait. And we wait. And nothing.

KS: Amyyyyyyy.

AG: Then my friend Nancy Woodruff, whom I used to be in a writers’ group with in London, invites me to a party for her book launch in New York. So, I gratefully accept, fly to New York, and go to this party. And there is Amy Einhorn, who is very lovely, and just about remembers who I am, and tells me she is still reading the manuscript. And I smile bravely and say, terrific!

Amy read the book and wanted to make an offer. But, she had warned, it needed a lot of work. So she and I spoke on the telephone several times, for several hours. She needed to see if I was willing to take her notes, and I needed to see that I was happy with the general direction she wanted to steer me in.

There was other stuff that she, and I quote, “didn’t love.” For example – the family’s business was originally a barbershop. She couldn’t see the logic of it, and wondered if there might be something else… and so I suggested a restaurant. Immediately this opened up a wealth of other avenues I could take the story down. In addition, the female characters could work there, too. It was a simple idea – although it required a LOT of rewriting – which infinitely improved the book.

So we talked and talked. And then I got a nine page letter with very specific editorial comments from her. And that letter was my template for the next rewrite – which took another six months.

I submitted the revised manuscript, and it came back two or three times with more comments from Amy as she gently guided me, encouraging certain themes and slowly pruning and honing all along the way. Real editing, in other words. That process took, I suppose, several more months.

She was very good not only at pulling out the broader themes, but also the close-in technical stuff – making suggestions as to how to restructure a particular passage or chapter – or series of chapters – to make more sense and to sustain tension or interest.

After the big structural edits were out of the way, we went through line edits, copy edits, all that fun stuff.

I’ve often heard it said that editors don’t edit any more – they merely acquire books which are ready to go. That may be true with some, but Amy was ready to roll up her sleeves and get to work on the text for as long as it took. I don’t know how many other editors would be prepared to do that.

KS: So now that we’ve gone over the narrative arc of the evolution of your novel, I want to ask, considering there were so many setbacks, if you ever had “a dark night of the soul” with this book, a moment where you feared all hope was lost?

AG: I wrote the first two-thirds of it not knowing how it was going to end. It’s grossly unprofessional of me, I know – but I tend to write very organically. Anyway, I became increasingly anxious as I got closer to the point when I knew I was going to have to make a decision about what happened to the characters. And I really didn’t know. Perhaps that’s why everyone rejected the first draft. The ending just wasn’t right.

There were times when I was tempted to throw up my hands and give up, but in the end I just refused. I had too much invested in the book to throw it away and start something else. I wanted to make THIS book the best I could

But – you just keep on keeping on. You haul your ass out of bed every morning, switch on the computer, and plod on. I always say that stamina and bloody-mindedness are the two most important attributes for a writer to have.

KS: You’re going to have to define bloody-mindedness for me so that I can use it in sentences all the time from now on.

AG: Is that not an expression that is used [in the United States]? It mean obstinancy. A refusal to give up.

KS: So, Frodo of course, does not come back from Mount Doom the same Hobbit? Have you thought about the ways, small and large, that the process of writing this novel has changed you as a writer/person?

AG: I’m a better writer than I was when I started. Writing is a craft like any other, and the more you do, the better (one hopes) you get.

I feel more equipped now to address more ambitious themes. One of the writers I admire most is Richard Powers, for the sheer scope of the books he writes. His novels have taught me to aim higher than I used to. To give you some context, my first few books were appalling, vacuous trash – the male equivalent of chick lit, only without the humor. A Good American is quite a departure away from that.

This book has made me think very hard about the curious position I find myself in – living 4,000 miles from my home, away from my family and friends. Writing it has helped crystalize some of that experience in my head and I feel equipped to deal with some of the stuff that occasionally arises as a result.

KS: Thanks so much for taking the time out to talk, Alex.

AG: I hope it was useful stuff. I do witter on.

KS: It’s good wittering.