The Reality of Reading Our Heroes

This content contains affiliate links. When you buy through these links, we may earn an affiliate commission.

This is a guest post from Carissa Lee. A proud Slytherin, Carissa spends her days researching for her Master’s Thesis at the University of Melbourne, with the ambition to publish a non-fiction work on Aesthetics in Indigenous Intracultural Theatre. Carissa also works as a freelance writer, researcher, actor and model. She is a stone-cold bibliophile with a soft spot for maudlin novels, classic literature, and rich autobiographies about rock stars and alternative thinkers. She resides in Melbourne with her partner, surrounded by inspiring cultural leaders and kick-arse academics who tell her she swears too much. Follow her on Twitter @rissless.

I have always loved Amanda Palmer and Marilyn Manson. I fell in love with them around the same age. Manson at sixteen, because I was trying to impress a boy I’d had a crush on since primary school, and Palmer at seventeen, because I hated men altogether by that stage. A lot can happen in a year, I guess. However, when you love an artist as much as I love these two, approach their biographies with caution.

Humans are not so easy to love, as we find in day-to-day life, and sometimes the reality of our heroes isn’t always an intimacy we are necessarily ready for. The idolising we have of these giants of another world seems to grow from a place of necessity.

Although I initially used Manson as a way to seem more appealing to someone, he was later used as a way to rebel from an abusive relationship, and in the end, he helped me learn that I’d become “a diamond that is tired of all the faces I’ve acquired” (“Spade,” The Golden Age of Grotesque) and gave me the strength to opt out of the freak masquerade I’d somehow signed up for. He was the ultimate middle finger to the world, and as I grew older, like him, I started believing that I wasn’t born with enough of them. At seventeen, and a restraining order from aforementioned ex later, this was the adrenalin-dump and aftermath of wreckage that had drained me of all the fight I’d had left.

I was sleep-deprived and feeling very much alone when I heard “Coin-Operated Boy” on Rage late one night, by the bizarre gothy-cabaret duet The Dresden Dolls. Amanda Palmer’s beautiful, raw, out-of-key melodies and honest lyrics saved me from the deepest of depressions, and lifted me back into Mansonesque fighting spirit once again.

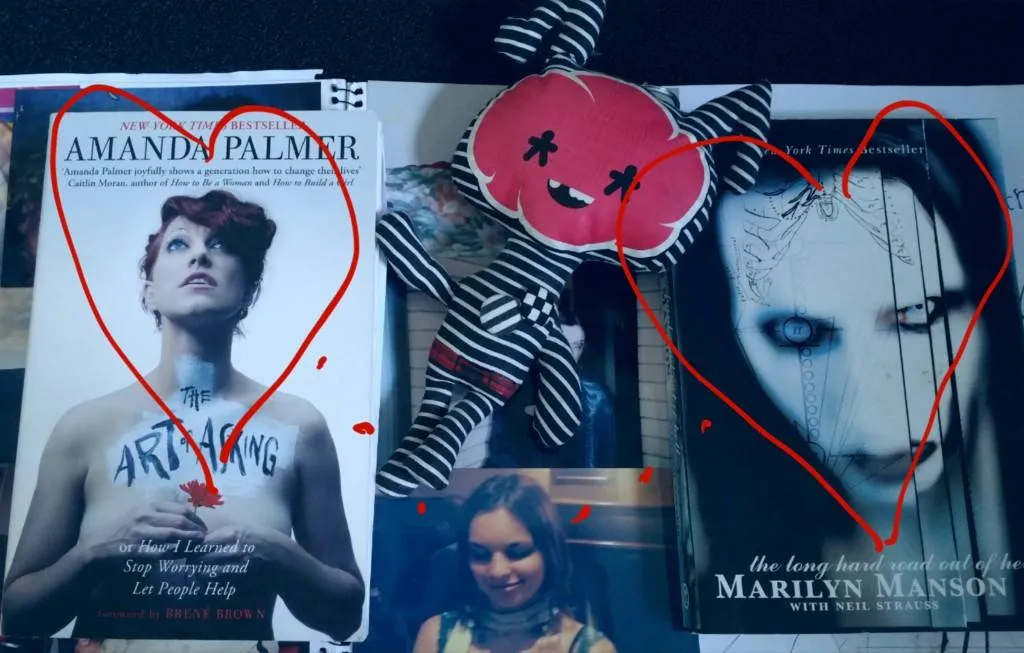

Later, in my early twenties, I read Manson’s biography, written in accompaniment with a favourite Rolling Stones author Neil Strauss, The Long Hard Road Out of Hell. At first I was taken aback by his vulnerability in writing of his early years as a teen, introduced by a dusty scene of discovering pornography depicting acts of beastiality in his grandfather’s basement.

Later we are met with his surprising initial terror of God during his early years of schooling. Reading of the horror stories of eventual apocalypse he was spoon-fed at the Christian heritage school he attended, I was left only relieved when his eventual turning point in life came at age 15, when he decided that he no longer believed in God. Fifteen is a recurring and significant number with Manson, which I love. However, once Manson was moved to public school, his eagerness to lose his virginity and become the infamous God of Fuck that we all know and love, led him down a somewhat steep path of bizarre illnesses and injuries, getting beaten up by jealous boyfriends, and STDs. The graphic honesty of retelling the discovery of crabs in his pubic hair definitely killed what little physical attraction I’d had for him at the time (and believe me, there wasn’t much). However, what really got me was his admission to coaxing people into friendship, and once he had them in a moment of vulnerability, he would intentionally emotionally destroy them by any means necessary. His stories of drugs and sexcapades were all to be expected (a surprisingly abusive relationship and repeated heartache for him, not-so-much) and the journey of his friendship with Trent Reznor left me sad, and hoping they might be friends again one day. In all of the content I was not yet ready to read, Manson was honest in his delivery. He didn’t feign intentions other than what was, and it was almost a sense of “do you still love me?” at the end of it. And because of this, I do.

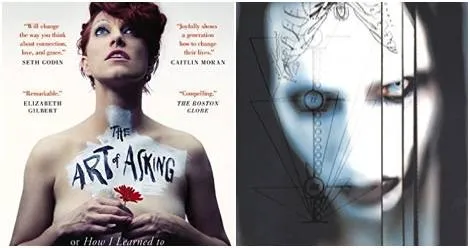

In my late twenties, I was so thrilled that now solo artist Amanda Palmer had released her book The Art of Asking. Not only a biography, but a little bit of an insight into her journey as an emerging artist, following her TED Talk by the same title (which you can watch here).

Amanda Palmer has always been a strong female figure for me. Not only because of her music, but because of her candour in the face of shit topics like break-ups and asking for help when you need it, and having been abused, telling a reputable record label to go to hell for asking her to be something she’s not, and still getting on with making music, getting married, and writing a book.

She tells of her humbling beginnings as a street performer The Eight-foot-bride, and learning to become acquainted with this trusting exchange of asking and receiving from passers-by as a means to make a living. However, she has been a subject of controversy with her use of crowd-funding to get an album put together since her drop from the label mentioned above.

Through blogging, an insanely active social media presence, and just taking the time to get to know her fans and gifting her donors, she was able to raise 1.2 million dollars to go towards her album. So here lies the rub. In her book she is quite straightforward about getting fans to perform with her on tour for free, or sometimes passing a hat around, asking for donations to pay the band. Not to mention her regular opting for couch-surfing with strangers. That was one thing that really got to me in this book– although there were tales of wonderful people doing kind things, there was always the odd douchebag who’d take it too far (like one audience-member at a gig who thought it was fine to pretty much molest her), and you’ve only got to listen to her music to know that she’s encountered proper fuckwits before, but the risks not only she took, but she encouraged her performers to take when on tour, opting to trust someone staying at their house when anything could go wrong.

The one thing that I really loved about the book was her relationship with Neil. How they awkwardly came together, the private pain they’d had to endure and overcome, as well as the turbulent days of Gaiman having to help Palmer condense her word count before sending her manuscript to her editor, having to remind her that he’d done this before, as well as the simply beautiful act of teaching him about grief. But one thing that seemed too bizarre (but in some way, I half-understood) was the fact that Amanda found it so difficult to ask her own husband for help. But I suppose when you’re an independent woman, which we all are these days, it can be a little tricky to ask for help and still feel like one. Within The Art of Asking, Amanda not only admits that she makes mistakes, she finds triumphs in the risks she takes coming good, because people are good. Families will give up beds for her and her performers, and she will receive, because she feels secure in the knowledge that her music has changed people’s lives for the better, and this is merely their half of the exchange. I imagine this would be a wonderful feeling to have, but I personally still wouldn’t feel ok about it.

I love Manson despite his shortcomings; however, Amanda’s image has changed for me. I suppose upon hearing the rumours of her allegedly ripping off artists to get free labour, I was wanting to discover a chapter in her book that would disprove it, as opposed to an entire publication dedicated to justifying it. I respect the way she lives, and if adult artists want to partake, then that’s their choice.

But if there’s one thing that Manson’s book (and life in general) has taught me, it’s that you can’t trust so openly, you can’t leave yourself so vulnerable. Whether it’s openly loving your audience and letting them draw on your naked body, or like Manson, leaving your acid-addled frame to the mercy of those around you, if there’s one question I’d like to leave, it’s a quote from Mr. Warner himself: “When you are taught to love everyone, to love your enemies, then what value does that place on your love?”

I have always loved Amanda Palmer and Marilyn Manson. I fell in love with them around the same age. Manson at sixteen, because I was trying to impress a boy I’d had a crush on since primary school, and Palmer at seventeen, because I hated men altogether by that stage. A lot can happen in a year, I guess. However, when you love an artist as much as I love these two, approach their biographies with caution.

Humans are not so easy to love, as we find in day-to-day life, and sometimes the reality of our heroes isn’t always an intimacy we are necessarily ready for. The idolising we have of these giants of another world seems to grow from a place of necessity.

Although I initially used Manson as a way to seem more appealing to someone, he was later used as a way to rebel from an abusive relationship, and in the end, he helped me learn that I’d become “a diamond that is tired of all the faces I’ve acquired” (“Spade,” The Golden Age of Grotesque) and gave me the strength to opt out of the freak masquerade I’d somehow signed up for. He was the ultimate middle finger to the world, and as I grew older, like him, I started believing that I wasn’t born with enough of them. At seventeen, and a restraining order from aforementioned ex later, this was the adrenalin-dump and aftermath of wreckage that had drained me of all the fight I’d had left.

I was sleep-deprived and feeling very much alone when I heard “Coin-Operated Boy” on Rage late one night, by the bizarre gothy-cabaret duet The Dresden Dolls. Amanda Palmer’s beautiful, raw, out-of-key melodies and honest lyrics saved me from the deepest of depressions, and lifted me back into Mansonesque fighting spirit once again.

Later, in my early twenties, I read Manson’s biography, written in accompaniment with a favourite Rolling Stones author Neil Strauss, The Long Hard Road Out of Hell. At first I was taken aback by his vulnerability in writing of his early years as a teen, introduced by a dusty scene of discovering pornography depicting acts of beastiality in his grandfather’s basement.

Later we are met with his surprising initial terror of God during his early years of schooling. Reading of the horror stories of eventual apocalypse he was spoon-fed at the Christian heritage school he attended, I was left only relieved when his eventual turning point in life came at age 15, when he decided that he no longer believed in God. Fifteen is a recurring and significant number with Manson, which I love. However, once Manson was moved to public school, his eagerness to lose his virginity and become the infamous God of Fuck that we all know and love, led him down a somewhat steep path of bizarre illnesses and injuries, getting beaten up by jealous boyfriends, and STDs. The graphic honesty of retelling the discovery of crabs in his pubic hair definitely killed what little physical attraction I’d had for him at the time (and believe me, there wasn’t much). However, what really got me was his admission to coaxing people into friendship, and once he had them in a moment of vulnerability, he would intentionally emotionally destroy them by any means necessary. His stories of drugs and sexcapades were all to be expected (a surprisingly abusive relationship and repeated heartache for him, not-so-much) and the journey of his friendship with Trent Reznor left me sad, and hoping they might be friends again one day. In all of the content I was not yet ready to read, Manson was honest in his delivery. He didn’t feign intentions other than what was, and it was almost a sense of “do you still love me?” at the end of it. And because of this, I do.

In my late twenties, I was so thrilled that now solo artist Amanda Palmer had released her book The Art of Asking. Not only a biography, but a little bit of an insight into her journey as an emerging artist, following her TED Talk by the same title (which you can watch here).

Amanda Palmer has always been a strong female figure for me. Not only because of her music, but because of her candour in the face of shit topics like break-ups and asking for help when you need it, and having been abused, telling a reputable record label to go to hell for asking her to be something she’s not, and still getting on with making music, getting married, and writing a book.

She tells of her humbling beginnings as a street performer The Eight-foot-bride, and learning to become acquainted with this trusting exchange of asking and receiving from passers-by as a means to make a living. However, she has been a subject of controversy with her use of crowd-funding to get an album put together since her drop from the label mentioned above.

Through blogging, an insanely active social media presence, and just taking the time to get to know her fans and gifting her donors, she was able to raise 1.2 million dollars to go towards her album. So here lies the rub. In her book she is quite straightforward about getting fans to perform with her on tour for free, or sometimes passing a hat around, asking for donations to pay the band. Not to mention her regular opting for couch-surfing with strangers. That was one thing that really got to me in this book– although there were tales of wonderful people doing kind things, there was always the odd douchebag who’d take it too far (like one audience-member at a gig who thought it was fine to pretty much molest her), and you’ve only got to listen to her music to know that she’s encountered proper fuckwits before, but the risks not only she took, but she encouraged her performers to take when on tour, opting to trust someone staying at their house when anything could go wrong.

The one thing that I really loved about the book was her relationship with Neil. How they awkwardly came together, the private pain they’d had to endure and overcome, as well as the turbulent days of Gaiman having to help Palmer condense her word count before sending her manuscript to her editor, having to remind her that he’d done this before, as well as the simply beautiful act of teaching him about grief. But one thing that seemed too bizarre (but in some way, I half-understood) was the fact that Amanda found it so difficult to ask her own husband for help. But I suppose when you’re an independent woman, which we all are these days, it can be a little tricky to ask for help and still feel like one. Within The Art of Asking, Amanda not only admits that she makes mistakes, she finds triumphs in the risks she takes coming good, because people are good. Families will give up beds for her and her performers, and she will receive, because she feels secure in the knowledge that her music has changed people’s lives for the better, and this is merely their half of the exchange. I imagine this would be a wonderful feeling to have, but I personally still wouldn’t feel ok about it.

I love Manson despite his shortcomings; however, Amanda’s image has changed for me. I suppose upon hearing the rumours of her allegedly ripping off artists to get free labour, I was wanting to discover a chapter in her book that would disprove it, as opposed to an entire publication dedicated to justifying it. I respect the way she lives, and if adult artists want to partake, then that’s their choice.

But if there’s one thing that Manson’s book (and life in general) has taught me, it’s that you can’t trust so openly, you can’t leave yourself so vulnerable. Whether it’s openly loving your audience and letting them draw on your naked body, or like Manson, leaving your acid-addled frame to the mercy of those around you, if there’s one question I’d like to leave, it’s a quote from Mr. Warner himself: “When you are taught to love everyone, to love your enemies, then what value does that place on your love?”

I have always loved Amanda Palmer and Marilyn Manson. I fell in love with them around the same age. Manson at sixteen, because I was trying to impress a boy I’d had a crush on since primary school, and Palmer at seventeen, because I hated men altogether by that stage. A lot can happen in a year, I guess. However, when you love an artist as much as I love these two, approach their biographies with caution.

Humans are not so easy to love, as we find in day-to-day life, and sometimes the reality of our heroes isn’t always an intimacy we are necessarily ready for. The idolising we have of these giants of another world seems to grow from a place of necessity.

Although I initially used Manson as a way to seem more appealing to someone, he was later used as a way to rebel from an abusive relationship, and in the end, he helped me learn that I’d become “a diamond that is tired of all the faces I’ve acquired” (“Spade,” The Golden Age of Grotesque) and gave me the strength to opt out of the freak masquerade I’d somehow signed up for. He was the ultimate middle finger to the world, and as I grew older, like him, I started believing that I wasn’t born with enough of them. At seventeen, and a restraining order from aforementioned ex later, this was the adrenalin-dump and aftermath of wreckage that had drained me of all the fight I’d had left.

I was sleep-deprived and feeling very much alone when I heard “Coin-Operated Boy” on Rage late one night, by the bizarre gothy-cabaret duet The Dresden Dolls. Amanda Palmer’s beautiful, raw, out-of-key melodies and honest lyrics saved me from the deepest of depressions, and lifted me back into Mansonesque fighting spirit once again.

Later, in my early twenties, I read Manson’s biography, written in accompaniment with a favourite Rolling Stones author Neil Strauss, The Long Hard Road Out of Hell. At first I was taken aback by his vulnerability in writing of his early years as a teen, introduced by a dusty scene of discovering pornography depicting acts of beastiality in his grandfather’s basement.

Later we are met with his surprising initial terror of God during his early years of schooling. Reading of the horror stories of eventual apocalypse he was spoon-fed at the Christian heritage school he attended, I was left only relieved when his eventual turning point in life came at age 15, when he decided that he no longer believed in God. Fifteen is a recurring and significant number with Manson, which I love. However, once Manson was moved to public school, his eagerness to lose his virginity and become the infamous God of Fuck that we all know and love, led him down a somewhat steep path of bizarre illnesses and injuries, getting beaten up by jealous boyfriends, and STDs. The graphic honesty of retelling the discovery of crabs in his pubic hair definitely killed what little physical attraction I’d had for him at the time (and believe me, there wasn’t much). However, what really got me was his admission to coaxing people into friendship, and once he had them in a moment of vulnerability, he would intentionally emotionally destroy them by any means necessary. His stories of drugs and sexcapades were all to be expected (a surprisingly abusive relationship and repeated heartache for him, not-so-much) and the journey of his friendship with Trent Reznor left me sad, and hoping they might be friends again one day. In all of the content I was not yet ready to read, Manson was honest in his delivery. He didn’t feign intentions other than what was, and it was almost a sense of “do you still love me?” at the end of it. And because of this, I do.

In my late twenties, I was so thrilled that now solo artist Amanda Palmer had released her book The Art of Asking. Not only a biography, but a little bit of an insight into her journey as an emerging artist, following her TED Talk by the same title (which you can watch here).

Amanda Palmer has always been a strong female figure for me. Not only because of her music, but because of her candour in the face of shit topics like break-ups and asking for help when you need it, and having been abused, telling a reputable record label to go to hell for asking her to be something she’s not, and still getting on with making music, getting married, and writing a book.

She tells of her humbling beginnings as a street performer The Eight-foot-bride, and learning to become acquainted with this trusting exchange of asking and receiving from passers-by as a means to make a living. However, she has been a subject of controversy with her use of crowd-funding to get an album put together since her drop from the label mentioned above.

Through blogging, an insanely active social media presence, and just taking the time to get to know her fans and gifting her donors, she was able to raise 1.2 million dollars to go towards her album. So here lies the rub. In her book she is quite straightforward about getting fans to perform with her on tour for free, or sometimes passing a hat around, asking for donations to pay the band. Not to mention her regular opting for couch-surfing with strangers. That was one thing that really got to me in this book– although there were tales of wonderful people doing kind things, there was always the odd douchebag who’d take it too far (like one audience-member at a gig who thought it was fine to pretty much molest her), and you’ve only got to listen to her music to know that she’s encountered proper fuckwits before, but the risks not only she took, but she encouraged her performers to take when on tour, opting to trust someone staying at their house when anything could go wrong.

The one thing that I really loved about the book was her relationship with Neil. How they awkwardly came together, the private pain they’d had to endure and overcome, as well as the turbulent days of Gaiman having to help Palmer condense her word count before sending her manuscript to her editor, having to remind her that he’d done this before, as well as the simply beautiful act of teaching him about grief. But one thing that seemed too bizarre (but in some way, I half-understood) was the fact that Amanda found it so difficult to ask her own husband for help. But I suppose when you’re an independent woman, which we all are these days, it can be a little tricky to ask for help and still feel like one. Within The Art of Asking, Amanda not only admits that she makes mistakes, she finds triumphs in the risks she takes coming good, because people are good. Families will give up beds for her and her performers, and she will receive, because she feels secure in the knowledge that her music has changed people’s lives for the better, and this is merely their half of the exchange. I imagine this would be a wonderful feeling to have, but I personally still wouldn’t feel ok about it.

I love Manson despite his shortcomings; however, Amanda’s image has changed for me. I suppose upon hearing the rumours of her allegedly ripping off artists to get free labour, I was wanting to discover a chapter in her book that would disprove it, as opposed to an entire publication dedicated to justifying it. I respect the way she lives, and if adult artists want to partake, then that’s their choice.

But if there’s one thing that Manson’s book (and life in general) has taught me, it’s that you can’t trust so openly, you can’t leave yourself so vulnerable. Whether it’s openly loving your audience and letting them draw on your naked body, or like Manson, leaving your acid-addled frame to the mercy of those around you, if there’s one question I’d like to leave, it’s a quote from Mr. Warner himself: “When you are taught to love everyone, to love your enemies, then what value does that place on your love?”

I have always loved Amanda Palmer and Marilyn Manson. I fell in love with them around the same age. Manson at sixteen, because I was trying to impress a boy I’d had a crush on since primary school, and Palmer at seventeen, because I hated men altogether by that stage. A lot can happen in a year, I guess. However, when you love an artist as much as I love these two, approach their biographies with caution.

Humans are not so easy to love, as we find in day-to-day life, and sometimes the reality of our heroes isn’t always an intimacy we are necessarily ready for. The idolising we have of these giants of another world seems to grow from a place of necessity.

Although I initially used Manson as a way to seem more appealing to someone, he was later used as a way to rebel from an abusive relationship, and in the end, he helped me learn that I’d become “a diamond that is tired of all the faces I’ve acquired” (“Spade,” The Golden Age of Grotesque) and gave me the strength to opt out of the freak masquerade I’d somehow signed up for. He was the ultimate middle finger to the world, and as I grew older, like him, I started believing that I wasn’t born with enough of them. At seventeen, and a restraining order from aforementioned ex later, this was the adrenalin-dump and aftermath of wreckage that had drained me of all the fight I’d had left.

I was sleep-deprived and feeling very much alone when I heard “Coin-Operated Boy” on Rage late one night, by the bizarre gothy-cabaret duet The Dresden Dolls. Amanda Palmer’s beautiful, raw, out-of-key melodies and honest lyrics saved me from the deepest of depressions, and lifted me back into Mansonesque fighting spirit once again.

Later, in my early twenties, I read Manson’s biography, written in accompaniment with a favourite Rolling Stones author Neil Strauss, The Long Hard Road Out of Hell. At first I was taken aback by his vulnerability in writing of his early years as a teen, introduced by a dusty scene of discovering pornography depicting acts of beastiality in his grandfather’s basement.

Later we are met with his surprising initial terror of God during his early years of schooling. Reading of the horror stories of eventual apocalypse he was spoon-fed at the Christian heritage school he attended, I was left only relieved when his eventual turning point in life came at age 15, when he decided that he no longer believed in God. Fifteen is a recurring and significant number with Manson, which I love. However, once Manson was moved to public school, his eagerness to lose his virginity and become the infamous God of Fuck that we all know and love, led him down a somewhat steep path of bizarre illnesses and injuries, getting beaten up by jealous boyfriends, and STDs. The graphic honesty of retelling the discovery of crabs in his pubic hair definitely killed what little physical attraction I’d had for him at the time (and believe me, there wasn’t much). However, what really got me was his admission to coaxing people into friendship, and once he had them in a moment of vulnerability, he would intentionally emotionally destroy them by any means necessary. His stories of drugs and sexcapades were all to be expected (a surprisingly abusive relationship and repeated heartache for him, not-so-much) and the journey of his friendship with Trent Reznor left me sad, and hoping they might be friends again one day. In all of the content I was not yet ready to read, Manson was honest in his delivery. He didn’t feign intentions other than what was, and it was almost a sense of “do you still love me?” at the end of it. And because of this, I do.

In my late twenties, I was so thrilled that now solo artist Amanda Palmer had released her book The Art of Asking. Not only a biography, but a little bit of an insight into her journey as an emerging artist, following her TED Talk by the same title (which you can watch here).

Amanda Palmer has always been a strong female figure for me. Not only because of her music, but because of her candour in the face of shit topics like break-ups and asking for help when you need it, and having been abused, telling a reputable record label to go to hell for asking her to be something she’s not, and still getting on with making music, getting married, and writing a book.

She tells of her humbling beginnings as a street performer The Eight-foot-bride, and learning to become acquainted with this trusting exchange of asking and receiving from passers-by as a means to make a living. However, she has been a subject of controversy with her use of crowd-funding to get an album put together since her drop from the label mentioned above.

Through blogging, an insanely active social media presence, and just taking the time to get to know her fans and gifting her donors, she was able to raise 1.2 million dollars to go towards her album. So here lies the rub. In her book she is quite straightforward about getting fans to perform with her on tour for free, or sometimes passing a hat around, asking for donations to pay the band. Not to mention her regular opting for couch-surfing with strangers. That was one thing that really got to me in this book– although there were tales of wonderful people doing kind things, there was always the odd douchebag who’d take it too far (like one audience-member at a gig who thought it was fine to pretty much molest her), and you’ve only got to listen to her music to know that she’s encountered proper fuckwits before, but the risks not only she took, but she encouraged her performers to take when on tour, opting to trust someone staying at their house when anything could go wrong.

The one thing that I really loved about the book was her relationship with Neil. How they awkwardly came together, the private pain they’d had to endure and overcome, as well as the turbulent days of Gaiman having to help Palmer condense her word count before sending her manuscript to her editor, having to remind her that he’d done this before, as well as the simply beautiful act of teaching him about grief. But one thing that seemed too bizarre (but in some way, I half-understood) was the fact that Amanda found it so difficult to ask her own husband for help. But I suppose when you’re an independent woman, which we all are these days, it can be a little tricky to ask for help and still feel like one. Within The Art of Asking, Amanda not only admits that she makes mistakes, she finds triumphs in the risks she takes coming good, because people are good. Families will give up beds for her and her performers, and she will receive, because she feels secure in the knowledge that her music has changed people’s lives for the better, and this is merely their half of the exchange. I imagine this would be a wonderful feeling to have, but I personally still wouldn’t feel ok about it.

I love Manson despite his shortcomings; however, Amanda’s image has changed for me. I suppose upon hearing the rumours of her allegedly ripping off artists to get free labour, I was wanting to discover a chapter in her book that would disprove it, as opposed to an entire publication dedicated to justifying it. I respect the way she lives, and if adult artists want to partake, then that’s their choice.

But if there’s one thing that Manson’s book (and life in general) has taught me, it’s that you can’t trust so openly, you can’t leave yourself so vulnerable. Whether it’s openly loving your audience and letting them draw on your naked body, or like Manson, leaving your acid-addled frame to the mercy of those around you, if there’s one question I’d like to leave, it’s a quote from Mr. Warner himself: “When you are taught to love everyone, to love your enemies, then what value does that place on your love?”