What Do 10 Years of the New York Times Young Adult Bestseller Lists Say About YA?

Prior to December 6, 2012, there was no standalone New York Times Best Seller list for young adult novels. At that time, young adult books were merged with other chapter books, creating a list that was a mix of young adult and middle grade titles. This change made it possible to better differentiate among the books for young readers — middle grade and young adult — and it opened up the possibility for more titles within each category to hit the list. The New York Times Best Seller list for Young Adults began by including sales totals that included hardcover, paperback, and ebooks.

Like other NYT Bestseller lists, the Young Adult lists have evolved over their ten years in existence. August 2015 marked the biggest shift since the lists development. Now, rather than a single list that captured sales of all formats of a book, the lists would separate out the Young Adult Bestsellers in paperback and hardcover; ebook sales were separated out; and series books would appear on a separate list that also included middle grade titles. This change made sense, as paperback titles dominated the bestseller list; it was much easier and cheaper to sell boatloads of copies of titles in paperback than in hardcover. This helped open up the lists to more titles and more accurately reflected what was selling and how.

But those changes did not last too long. In October 2017, the lists changed again. August of that year saw the end of the YA ebook list — a list wherein titles that were put on mega sale in that format were able to earn the designation of “New York Times Bestseller.” October brought the shift of the YA paperback bestseller list to a monthly roundup, keeping its YA hardcover as the prime list, published weekly. This year was particularly interesting for the New York Times YA Best Seller list, as it showed how easily the list could be manipulated with the right amount of time, money, and effort.

In 2013, I pulled together a look at the list and the demographics represented. The first post of two has, unfortunately, been lost to server migrations. The second post, though, is still available. The list at the time had been very white and very male dominated. This was when paperback and hardcover were combined and when ebook sales were a fraction of a fraction of sales.

This critical look at representation came at the height of book blogging, and it came at the same time the YA community engaged in large-scale discussions about representation…and the lack thereof. We Need Diverse Books launched in 2014, setting off significant changes in the industry. Those changes, still ongoing and still evolving, were certainly reflected in the New York Times Best Seller lists for Young Adults.

Now that the list has celebrated its tenth birthday, what has changed? What can we learn or observe from a decade of tracking the bestselling literature in a category?

Data Limitations and Notes

First and foremost: we have no idea how the lists are tabulated. It is ostensibly sales, but sales from where remains a question. There are reporting institutions, but not all bookstores report sales to the NYT. What is listed represents some metric of sales, and yet, it might not actually represent true sales of any title. This is especially true for smaller publishers, who can see significant sales of their titles but they may never be picked up by the Times.

All of the information below is pulled from the Young Adult Hardcover lists only. Because the lists have shifted over the years, including and excluding paperbacks and series books, it made the most sense to stick to one standard. The lists pre-2015 will have all formats, but following those lists, the titles explored were only those on the hardcover list.

The biggest limitation in this look at ten years of the New York Times Young Adult Best Sellers list is, perhaps, the most frustrating. Full lists of data from 2012 to 2015 are not included. Despite several methods of searching, deep dives into paper’s archives, searches in archived paper databases, and asking for help on social media, the full ten title lists are nowhere to be found. Instead, all of the data for Young Adult NYT Best Sellers from 2012 to 2015 include only the top five titles; they were all archived in an Open Data archive, and thus, they represent only half of the titles which hit the list in the early years.

Despite that limitation, there is still a lot to be learned and considered with the data.

The work of compiling, sorting, and categorizing the books on ten years’ worth of lists took a lot of time, and there was certainly an element of subjectivity involved. I’ve been blogging about YA books and the YA book world for over 15 years, and my knowledge of this category is broad and deep. That said, there will be mistakes, and there will be categorization choices you don’t agree with. I welcome you to do your own work and share your findings if something doesn’t sit right with you.

The data used begins December 6, 2012, the first day of a separate YA list. The final data used is December 25, 2022.

That all articulated, let’s dive in.

The NYT YA Bestseller List By The Numbers

Total Number of Books on the New York Times YA Bestseller List

Remember that there are three years’ of data that only include half of the lists, so these numbers reflect the available data and not the titles which are missing.

- A total of 4,446 YA books have graced the lists

- 522 unique YA books have hit the list

Gender Breakdown: Who Is Hitting the List?

Determining the gender breakdown of the New York Times Young Adult Best Sellers list is tricky. It requires defining gender to begin with, which we know is fluid as opposed to rigid. To make determinations on gender, I went by the pronouns used by each of the authors. This is not deterministic of gender, but it is the easiest tool to create a breakdown by gender for comparison sake.

There were three broad categories of gender assessed: those using he/him pronouns were put in the “male” bucket; those using she/her pronouns were put in the “female” bucket; those using they/them or any neo-pronouns were put into the “nonbinary/genderqueer” bucket.

An additional hiccup in this data is that two authors are utilizing pseudonyms that could account for multiple authors of any number of genders. We know that Pittacus Lore is a fictitious name for authors working in the James Frey packager, and we know that A.W. Jantha, the author attributed to the book Hocus Pocus and the All New Sequel, is also a pseudonym. I’ve put books like that under the “??” bucket for gender.

Author gender was counted each time they had a book on the list. Again: three years’ of data only include half of the full list. These numbers below represent singular authors on the list, so books where only one author is named.

- 2,941 were female authors by themselves

- 874 were male authors by themselves

- 144 authors were included in the nonbinary/genderqueer category

- 36 pseudonyms were used, constituting the “??” gender

But solo authors weren’t the only ones making the list. There were many author duos, author/illustrator collaborations, and other combinations of people working on a book that hit the list. I categorized the genders of these authors based on how they were listed on the book title. In some cases, this meant that alphabetically, a female author came before her male coauthor; in other cases, the male author came first because he was the primary author and the female coauthor or illustrator was secondary.

Again: this is per time the title appeared on the list. There were not, for example, 48 different groups of four men who wrote a YA bestseller together; in that instance, it represents a single group of four showing up 48 times. It may be the case there were several different female writing duos included in the count for that category, though.

- 29 women collaborated with other women on their YA bestsellers

- 1 trio of women created a bestseller

- 12 groups of four women collaborated on work together

- 3 groups of six women collaborated on a book together

- 139 collaborations happened between women and men (that is, the female author was listed first)

- 76 men collaborated with women (that is, the male author was listed first)

- 1 male author worked with 2 female collaborators

- 141 men collaborated with other male authors

- 48 male quad writing groups were represented

Some firsts:

- The first female author on the YA Best Seller list is Veronica Roth for Divergent, which reached #2 on the very first list, December 6, 2012. Insurgent was on the same list at #4.

- The first openly nonbinary author to grace the list was Marike Nijkamp with This Is Where It Ends, March 20, 2016.

Diversity in the Young Adult New York Times Bestsellers List

Same caveat here applies in that the first three years do not include the entire lists, so data here may be undercounting.

Each author’s identity was determined by their own bios. If they included their ethnic or racial background as one that was not white, they were included here. It is and has to be imperfect, but it is as close as can be accurate. Again, this number indicates instances, not unique numbers. So one author could be included in this count 50 or 100 times.

A hitch in this is as follows: these numbers represent individual BOOKS, not individual authors. In some cases, this means books written by an author duo composed of one Black author and one white author was popped into the bucket of “diverse books.” A book by six Black authors was a singular title, as opposed to six separate titles.

- 1,347 diverse books were represented on the list

In isolation, what does this number even mean? 1,347 books out of 4,446 were diverse. This comes out to about 30% of the total titles were by authors of color. Not too bad, given that the U.S. population itself is roughly 40% people of color.

More interesting, though, is the TREND in diverse books.

- 2012: 2 diverse books

- 2013: 2 diverse books

- 2014: 1 diverse book

- 2015: 20 diverse books

- 2016: 52 diverse books

- 2017: 165 diverse books

- 2018: 182 diverse books

- 2019: 228 diverse books

- 2020: 258 diverse books

- 2021: 244 diverse books

- 2022: 193 diverse books

In 2017, we saw the publication of Angie Thomas’s phenomenal The Hate U Give, which remained on and off the bestseller list up until the last year. We saw diverse books hit their peak in representation on the list in 2020, and they have been slipping back down again in the last two years. In 2020, diverse books represented almost half of the total books on the list.

Does the dip in diverse books in the last two years represent anything? It’s hard to say. The big players on the YA Best Sellers list in the last two years have been books by Karen McManus, Holly Jackson, and franchise tie-ins to Hocus Pocus, The Nightmare Before Christmas, and Star Wars, the vast majority of which are by white authors.

This is an area to keep an eye on. Is the marketing of books by authors of color softening? Is a lack of adaptations by these authors contributing to the slip in numbers? We know that both play a role in ensuring the list accurately represents not only the books being published but also in the readers being served.

Recall that series books move from the hardcover bestseller list to the series list. This dip could be representative of books making the leap in lists.

Some firsts:

- The first author of color to hit the New York Times Young Adult Best Sellers list: Gabby Douglas, for her memoir Grace, Gold, and Glory.

- Don’t want to count a celebrity memoir? Keeping in mind that the data from early lists is missing, the next author of color to land on the list is Prodigy by Marie Lu, on February 17, 2013.

Queer Books on the YA Bestsellers List of the New York Times

How do you quantify queerness of books? Is it the author’s identity, suggesting that whatever a queer author writes comes from a queer perspective? If so, then what happens when the author’s sexuality evolves? Is one more “real” than the other? (The answer is no.)

If it’s content of the book, this, too, gets tricky. Queer books have queer-themed content, but does that mean it needs to be a main character who is queer? Or is it just a mention of something related to the LGBTQ+ community? A side character?

The answer is there is no good answer.

Malinda Lo has been at the forefront of tracking queer YA since the beginning of her career. I cannot recommend enough that you spend some time with her data, as she’s thought through these questions and offered insights into the patterns and trends in queer YA books.

For the sake of this data collection, “queer” is defined as a major theme or a major character in the story. This could be indicated by personal knowledge of the book, or by a search for how frequently the book is categorized as LGBTQ+ on bookish social media. This may be an under, as opposed to over, count, and I think that is important to consider. Books where queerness is not overt — books like The Perks of Being a Wallflower, which many consider now to have a big queer theme — are not included because they were not seen as such in 2012.

The number here is based on books, not on authors, and it is inclusive of repeat titles, rather than unique titles.

- 268 queer books have appeared on the YA bestseller list.

That is roughly 5% of the lists, representing what major polls have suggested as about the rate of U.S. individuals identifying as queer. Of course, the core audience of YA books — young people — identify at higher rates, so this number is tiny in comparison.

How does this look by year?

- 2012: 0 queer books

- 2013: 0 queer books

- 2014: 0 queer books

- 2015: 2 queer books

- 2016: 10 queer books

- 2017: 4 queer books

- 2018: 35 queer books

- 2019: 19 queer books

- 2020: 18 queer books

- 2021: 34 queer books

- 2022: 143 queer books

The growth here is extremely promising to see.

And some firsts to know. Again, remember the data for three years is incomplete, so this is based off accessible information:

- David Levithan was the first openly queer author with a book on the list (Another Day, which landed March 20, 2015)

- Not counting Another Day, which does not center the queer experience, the first queer YA book on the list was Carry On by Rainbow Rowell on October 25, 2015.

Nonfiction on the YA Best Seller List

Despite campaigns for the New York Times to consider YA nonfiction separate from fiction, the lists continue to count nonfiction against fiction. What this means is most nonfiction never has a shot at the list. The titles that do land there are those with a celebrity name attached or that are by big name YA authors. I’ve included, for example, poetry as nonfiction, so Ain’t Burned All The Bright by Jason Reynolds and Jason Griffin is included here.

- 197 titles over ten years were nonfiction

YA nonfiction is diverse, wide-ranging, and often heavily ignored by major industry resources. These numbers show just that.

Fun Trends in YA Seen via the NYT Best Seller List

We’ve now looked at some of the biggest categories and topics that have emerged on the New York Times Best Selling Young Adult Books list. How about some fun or off-beat stuff, too?

- The Hate U Give is the most frequently occurring book title, followed by One Of Us Is Lying, The Fault In Our Stars, Looking for Alaska, and Five Feet Apart.

- The year with the most royalty related book titles — think Court, Queen, Sword — was 2016.

- But in 2017, those titles shifted to a celestial theme: Moon, Stars, Night, Sun.

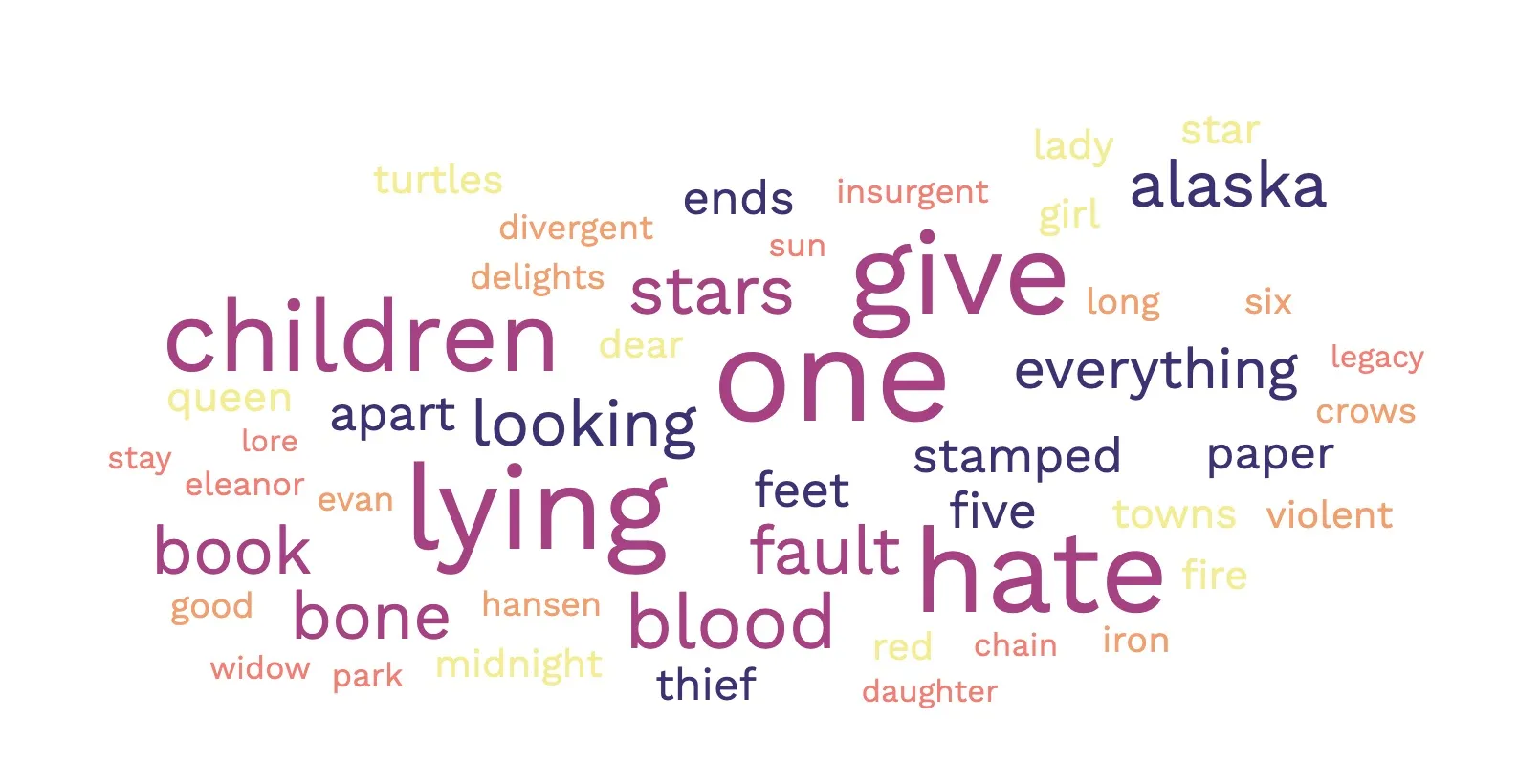

Finally, for a little more fun, here’s a WordCloud visualizing the most popular words in YA book titles from the last 10 years of the New York Times YA Best Seller list.

If there’s one thing to take away from this, let it be that the louder we advocate for inclusive literature — books by and about BIPOC and queer people — the more money we put into ensuring their success…those successes pay off.

But in a culture where these books are on the line, where radical book banners want to eradicate these books and the people behind them and represented in them, we need to do a lot more than simply buy them. We need to show up on the front lines and demand intellectual freedom for ALL.