The Life and Work of Christine de Pizan, Feminist Writer of the Middle Ages

This content contains affiliate links. When you buy through these links, we may earn an affiliate commission.

Women during the Middle Ages tend to be seen as oppressed, robbed of all agency, and constantly under the guardianship of a man. Even though the lives of women during the Middle Ages were more circumvented than the lives of women living in Europe and the United States today, the idea that they lacked control is not entirely true.

Nor is it entirely true that medieval women were prevented from expressing their views in public, or that they were prevented from pursuing artistic careers because of the burdens laid upon them as mothers, wives, and daughters.

In fact, during the Middle Ages there were plenty of women who led independent lives, excelling as politicians, artists, and writers. One of these women was Christine de Pizan, a French renaissance poet who is the first known woman in France to have made her living solely from writing. Christine is also known as one of the earliest feminist writers, publishing protest poems, utopian fiction about a city inhabited only by women, and a celebration of the achievements of Joan of Arc.

Born in 1365 in Venice, Christine de Pizan grew up at the court of King Charles V of France, where her father was the royal astrologer and alchemist. The royal court in Paris gave Christine ample opportunity to explore the libraries at the palace and to participate in the intellectual environment.

At the age of fifteen, Christine married Etienne de Castel, employed at the royal court as court secretary. Together they had three children before he passed away ten years later. Barely twenty-five years old and a widow, Christine faced the daunting task of supporting her three children, as well as her widowed mother.

Christine turned to writing.

Throughout her writing career Christine de Pizan produced a total of ten volumes of poetry, most notably a number of so-called complaints, which in medieval literature means “protest poems.” Complaints were short political songs or satirical poems targeting a specific vice or injustice.

Born in 1365 in Venice, Christine de Pizan grew up at the court of King Charles V of France, where her father was the royal astrologer and alchemist. The royal court in Paris gave Christine ample opportunity to explore the libraries at the palace and to participate in the intellectual environment.

At the age of fifteen, Christine married Etienne de Castel, employed at the royal court as court secretary. Together they had three children before he passed away ten years later. Barely twenty-five years old and a widow, Christine faced the daunting task of supporting her three children, as well as her widowed mother.

Christine turned to writing.

Throughout her writing career Christine de Pizan produced a total of ten volumes of poetry, most notably a number of so-called complaints, which in medieval literature means “protest poems.” Complaints were short political songs or satirical poems targeting a specific vice or injustice.

Her most famous work today is the utopian story The Book of the City of Ladies, which was published in 1405. The story highlights the accomplishments of women, resulting in the establishment of a city populated only by women. In the sequel, The Treasure of the City of Ladies, also published in 1405, Christine furthers her argument that women can make great contributions to society if they are allowed a level playing field.

Christine de Pizan died in 1430. The previous year, she had completed her final work, titled Le Ditié de Jeanne d’Arc (Song in Honor of Joan of Arc). Here, she celebrates the victories and achievements of Joan of Arc, the only known such celebration written in French during Joan’s lifetime.

In her writings, Christine de Pizan took aim at the patriarchy, arguing in favor of women’s rights to an education and their right to be considered as men’s equals. It is uncertain how widely spread her books and poems were among the French population, but it is believed that her ideas did have an impact on French legislation.

But how could Christine de Pizan criticize the misogyny and injustices of medieval France so openly and get away with it?

She achieved this because of her high social status and her connections among the royal court. Also, she embedded her criticism and satire in Christian thought and doctrine. But most importantly, she was a widow. Widows in the Middle Ages were their own legal guardians. Soon after her husband died, Christine de Pizan made the conscious decision not to remarry and instead focus on her writing.

And we owe her a debt of gratitude for it.

In addition to the titles mentioned above, Christine de Pizan’s work is also available in English in the following editions.

Her most famous work today is the utopian story The Book of the City of Ladies, which was published in 1405. The story highlights the accomplishments of women, resulting in the establishment of a city populated only by women. In the sequel, The Treasure of the City of Ladies, also published in 1405, Christine furthers her argument that women can make great contributions to society if they are allowed a level playing field.

Christine de Pizan died in 1430. The previous year, she had completed her final work, titled Le Ditié de Jeanne d’Arc (Song in Honor of Joan of Arc). Here, she celebrates the victories and achievements of Joan of Arc, the only known such celebration written in French during Joan’s lifetime.

In her writings, Christine de Pizan took aim at the patriarchy, arguing in favor of women’s rights to an education and their right to be considered as men’s equals. It is uncertain how widely spread her books and poems were among the French population, but it is believed that her ideas did have an impact on French legislation.

But how could Christine de Pizan criticize the misogyny and injustices of medieval France so openly and get away with it?

She achieved this because of her high social status and her connections among the royal court. Also, she embedded her criticism and satire in Christian thought and doctrine. But most importantly, she was a widow. Widows in the Middle Ages were their own legal guardians. Soon after her husband died, Christine de Pizan made the conscious decision not to remarry and instead focus on her writing.

And we owe her a debt of gratitude for it.

In addition to the titles mentioned above, Christine de Pizan’s work is also available in English in the following editions.

Christine de Pizan (Charity Cannon Willard, editor, Sumner Willard, translator), The Book of Deeds of Arms and of Chivalry. Because of its subject matter, one of Christine de Pizan’s lesser known works. Published by Christine de Pizan in 1410, this book discusses the technology and strategies of French contemporary warfare. For a long time it was claimed that Christine had only copied the military writings of others, but as the editor and the translator of this edition show, Christine de Pizan knew her warfare as well as she knew her French renaissance rhetoric.

Christine de Pizan (Charity Cannon Willard, editor and translator), The Writings of Christine de Pizan. A collection of excerpts of Christine de Pizan’s works, including The Book of the City of Ladies and Song in Honor of Joan of Arc.

Christine de Pizan (Charity Cannon Willard, editor, Sumner Willard, translator), The Book of Deeds of Arms and of Chivalry. Because of its subject matter, one of Christine de Pizan’s lesser known works. Published by Christine de Pizan in 1410, this book discusses the technology and strategies of French contemporary warfare. For a long time it was claimed that Christine had only copied the military writings of others, but as the editor and the translator of this edition show, Christine de Pizan knew her warfare as well as she knew her French renaissance rhetoric.

Christine de Pizan (Charity Cannon Willard, editor and translator), The Writings of Christine de Pizan. A collection of excerpts of Christine de Pizan’s works, including The Book of the City of Ladies and Song in Honor of Joan of Arc.

Christine de Pizan (Renate Blumenfeld-Kosinski, editor, and Kevin Brownlee, translator), Selected Writings of Christine de Pizan. This Norton Critical Edition contains eighteen of Christine de Pizan’s writings, complete with annotations and manuscript illuminations. Also included in this volume are critical essays discussing the selected texts.

Christine de Pizan (Renate Blumenfeld-Kosinski, editor, and Kevin Brownlee, translator), Selected Writings of Christine de Pizan. This Norton Critical Edition contains eighteen of Christine de Pizan’s writings, complete with annotations and manuscript illuminations. Also included in this volume are critical essays discussing the selected texts.

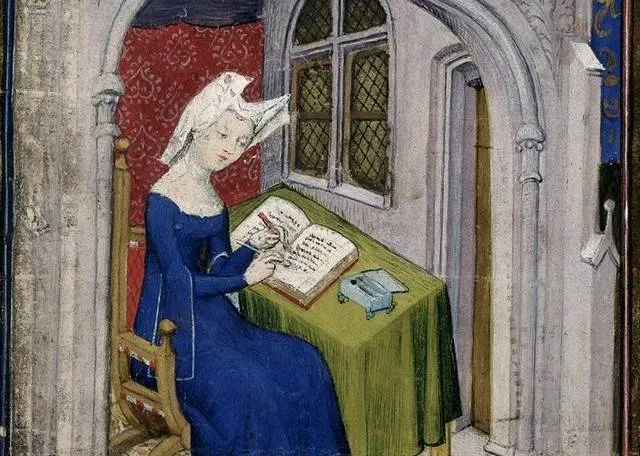

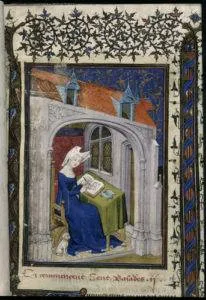

Portrait of Christine de Pizan (British Library, Harley MS 4431 f. 4).

Her most famous work today is the utopian story The Book of the City of Ladies, which was published in 1405. The story highlights the accomplishments of women, resulting in the establishment of a city populated only by women. In the sequel, The Treasure of the City of Ladies, also published in 1405, Christine furthers her argument that women can make great contributions to society if they are allowed a level playing field.

Christine de Pizan died in 1430. The previous year, she had completed her final work, titled Le Ditié de Jeanne d’Arc (Song in Honor of Joan of Arc). Here, she celebrates the victories and achievements of Joan of Arc, the only known such celebration written in French during Joan’s lifetime.

In her writings, Christine de Pizan took aim at the patriarchy, arguing in favor of women’s rights to an education and their right to be considered as men’s equals. It is uncertain how widely spread her books and poems were among the French population, but it is believed that her ideas did have an impact on French legislation.

But how could Christine de Pizan criticize the misogyny and injustices of medieval France so openly and get away with it?

She achieved this because of her high social status and her connections among the royal court. Also, she embedded her criticism and satire in Christian thought and doctrine. But most importantly, she was a widow. Widows in the Middle Ages were their own legal guardians. Soon after her husband died, Christine de Pizan made the conscious decision not to remarry and instead focus on her writing.

And we owe her a debt of gratitude for it.

In addition to the titles mentioned above, Christine de Pizan’s work is also available in English in the following editions.

Her most famous work today is the utopian story The Book of the City of Ladies, which was published in 1405. The story highlights the accomplishments of women, resulting in the establishment of a city populated only by women. In the sequel, The Treasure of the City of Ladies, also published in 1405, Christine furthers her argument that women can make great contributions to society if they are allowed a level playing field.

Christine de Pizan died in 1430. The previous year, she had completed her final work, titled Le Ditié de Jeanne d’Arc (Song in Honor of Joan of Arc). Here, she celebrates the victories and achievements of Joan of Arc, the only known such celebration written in French during Joan’s lifetime.

In her writings, Christine de Pizan took aim at the patriarchy, arguing in favor of women’s rights to an education and their right to be considered as men’s equals. It is uncertain how widely spread her books and poems were among the French population, but it is believed that her ideas did have an impact on French legislation.

But how could Christine de Pizan criticize the misogyny and injustices of medieval France so openly and get away with it?

She achieved this because of her high social status and her connections among the royal court. Also, she embedded her criticism and satire in Christian thought and doctrine. But most importantly, she was a widow. Widows in the Middle Ages were their own legal guardians. Soon after her husband died, Christine de Pizan made the conscious decision not to remarry and instead focus on her writing.

And we owe her a debt of gratitude for it.

In addition to the titles mentioned above, Christine de Pizan’s work is also available in English in the following editions.

Christine de Pizan (Charity Cannon Willard, editor, Sumner Willard, translator), The Book of Deeds of Arms and of Chivalry. Because of its subject matter, one of Christine de Pizan’s lesser known works. Published by Christine de Pizan in 1410, this book discusses the technology and strategies of French contemporary warfare. For a long time it was claimed that Christine had only copied the military writings of others, but as the editor and the translator of this edition show, Christine de Pizan knew her warfare as well as she knew her French renaissance rhetoric.

Christine de Pizan (Charity Cannon Willard, editor and translator), The Writings of Christine de Pizan. A collection of excerpts of Christine de Pizan’s works, including The Book of the City of Ladies and Song in Honor of Joan of Arc.

Christine de Pizan (Charity Cannon Willard, editor, Sumner Willard, translator), The Book of Deeds of Arms and of Chivalry. Because of its subject matter, one of Christine de Pizan’s lesser known works. Published by Christine de Pizan in 1410, this book discusses the technology and strategies of French contemporary warfare. For a long time it was claimed that Christine had only copied the military writings of others, but as the editor and the translator of this edition show, Christine de Pizan knew her warfare as well as she knew her French renaissance rhetoric.

Christine de Pizan (Charity Cannon Willard, editor and translator), The Writings of Christine de Pizan. A collection of excerpts of Christine de Pizan’s works, including The Book of the City of Ladies and Song in Honor of Joan of Arc.

Christine de Pizan (Renate Blumenfeld-Kosinski, editor, and Kevin Brownlee, translator), Selected Writings of Christine de Pizan. This Norton Critical Edition contains eighteen of Christine de Pizan’s writings, complete with annotations and manuscript illuminations. Also included in this volume are critical essays discussing the selected texts.

Christine de Pizan (Renate Blumenfeld-Kosinski, editor, and Kevin Brownlee, translator), Selected Writings of Christine de Pizan. This Norton Critical Edition contains eighteen of Christine de Pizan’s writings, complete with annotations and manuscript illuminations. Also included in this volume are critical essays discussing the selected texts.