The Joy of Seeing Yourself in Literature

In the spring of last year when I was in the throes of a complicated identity crisis, reading Filipina author Mia P. Manansala’s cozy mystery debut Arsenic and Adobo felt like validating my entire existence. With its mention of tasty Filipino fare, I felt a shift in me as I was struggling to find a sense of my place in this world. Since most of the time I don’t see myself in the books I read, it made me feel seen long after I turned the last page.

Though I read many books written by authors from my community, this cozy culinary mystery somehow stirred up emotions in me different from what I usually experience. There aren’t as many books published as there should in the United States that draw attention to the traditions and cultures of marginalized groups. There are even fewer Filipino American books that do.

The last book that made me feel this way was America Is Not the Heart by Elaine Castillo, which I read way back in 2018. In it, there are untranslated words from my native language, Pangasinan. Pangasinan doesn’t get a lot of mainstream mentions, nor does it have social prestige like a language like French does. It’s basically lying on its deathbed.

There’s also a character in Castillo’s book that comes from the very place where I was born, somewhere in the north of the Philippines. Having read those untranslated texts in mainstream publishing and having been acquainted with this particular character that speaks my native tongue made me feel proud of my roots. The effect was instantaneous: I felt…validated. Like, somehow, my place in this world would always feel secure, no matter where I was. For many people, this may feel like a big leap. For me, it was a rare, ecstatic moment.

Unfortunately, that validating moment came years after I joined the publishing industry, which I had been disappointed to discover was still “overwhelmingly white.” I learned that there were hardly ever books published with people of color as central characters. This deep lack of diverse material makes people like me feel ostracized. Forgotten. Overlooked.

Day of Reckoning

This needs to change by the industry’s acknowledgment of its prejudiced past, as everything is rooted to this very industry we are all in. “Author diversity at major publishing houses has increased in recent years, but white writers still dominate,” wrote The New York Times opinion writers in 2020, following the Black Lives Matter protests. Just reading about how authors of color are paid significantly less than their white counterparts is just unbelievable and sad. By fixing this glaring pay disparity, I hope that more books by other people whose struggles we haven’t heard of yet will get published more often. I hope that it will encourage more unknown voices to be heard.

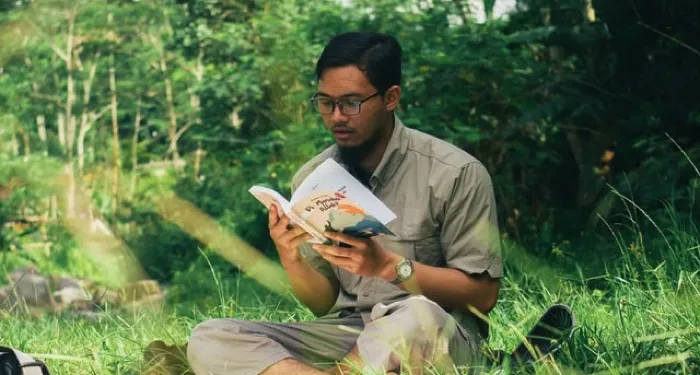

Representation, which can be explained as simply as seeing yourself in the books you read, is a triumph for diversity. It also helps to dispel some long-held racial stereotypes. It can make one feel like they belong to a society that has previously shunned them. It can also make marginalized people feel that their struggles are valid, too, and that they deserve to carve spaces for themselves. Whenever I read something in books that hits close to home — something that is similar to my experiences in life — I involuntarily smile. Sometimes, I can’t help but tear up.

Fortunately, works from people of color are starting to get more recognition. These days, I see books by Asian, Black, and Latine authors in many different lists and bookshelves. Many publishers are also making changes to how they usually work. Still, I hope that it’s not only a passing trend or some corporate tokenism. I hope that companies aren’t jumping on the bandwagon to only end up having their diverse titles archived, forgotten, or shelved for a year.

After that defining event with Arsenic and Adobo (and ultimately, the rest of Tita Rosie’s Kitchen Mystery series) and America Is Not the Heart, I never stopped looking for books that incorporate characters that look like me, act like me, and speak like me. Unfortunately, my search has not resulted in as many books as I would like. That’s why, though my experience may seem trivial for some, for people like me who rarely see themselves represented in the books being published these days, representation is consequential.

To see yourself in the books you read is an acknowledgment of your reality. That you’re alive, you’re here, you belong, and the world acknowledges your presence. That no matter how different you feel you are from the rest, it means that your whole life matters, too.