The Hatred of Poetry: A Bibliography

This content contains affiliate links. When you buy through these links, we may earn an affiliate commission.

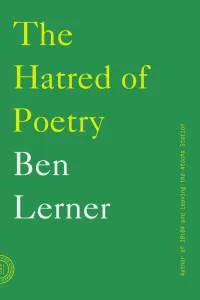

I had so much fun reading Ben Lerner’s The Hatred of Poetry last week. As you can tell from the title, the essay is about why we hate poetry. I thought that the book would be either a justification of this hatred, or perhaps a justification with a twist ending that would explain why we should all love poetry. It’s actually neither of those things. Rather, the author’s thesis is something like this: We all possess an indelible draw to poetry (capital P, Poetry), yet the poems themselves tend to the get in the way.

The essay proposes something sort of wonderful: that our hatred of poetry is not a hatred of the form itself, but an intuitive recognition that poetry is cursed to always fall short of its mark. Poetry is an ideal, and poems are real, and what is real is often problematic. So if you say you hate poetry, what you actually hate is perhaps not so much the words on the page and their particular combination, as the fact that poetry always forces us to confront the innate banality of human expression. It is a thesis that Lerner conveys with humor and grace and a superb ear toward the truly special moments that we experience when we encounter poetry.

So I recommend that you go read the book, particularly if you (like me) feel a certain ambivalence toward poetry in general. But in the meantime, here is a little bibliography (with spare annotation) because I especially enjoyed making a mental map of the poets and essayists that Lerner mentions. It’s always fun to see who exactly is floating around inside the head of a writer.

Beginning with the famous line: “I, too, dislike it” Lerner initiates his reflections on our hatred of the genre with an amusing tale of his choosing to memorize Marianne Moore’s “Poetry” (the 1967 version) in school.

The 7th century Caedmon (as read by Allen Grossman) is the first known poet in the English language, who, according to legend, was gifted the ability to praise God in song by an angel appearing in a dream. Allen Grossman draws from this story in his poem “The Caedmon Room” and in his 1983 essay “My Caedmon: Thinking about Poetic Vocation.” (Note: These pieces are not mentioned by name, but this is where he takes his observations about Caedmon from.)

The Republic by Plato, of course. Wherein the infamous argument is made that poets should be expelled from the Republic because they cannot write of truth but only of their imaginings.

The Defense of Poesy by Philip Sidney, Elizabethan poet and defender of the art, in which the author claims that poetry is superior to philosophy and history in that it elicits emotion.

Percy Bysshe Shelley, the one and only, who writes that “the most glorious poetry that has ever been communicated to the world is probably a feeble shadow of the original conception of the poet.” It’s an idea that is essential to Lerner’s own theory of poetry, concisely portraying the frustration with poetry’s infinite potential and finite effects.

Arthur Rimbaud and George Oppen: two famous poetic quitters who are also, according to Lerner, perennially popular among budding poets because they embody the vocation of the poet while shrugging off the burden of actual poetry.

I had so much fun reading Ben Lerner’s The Hatred of Poetry last week. As you can tell from the title, the essay is about why we hate poetry. I thought that the book would be either a justification of this hatred, or perhaps a justification with a twist ending that would explain why we should all love poetry. It’s actually neither of those things. Rather, the author’s thesis is something like this: We all possess an indelible draw to poetry (capital P, Poetry), yet the poems themselves tend to the get in the way.

The essay proposes something sort of wonderful: that our hatred of poetry is not a hatred of the form itself, but an intuitive recognition that poetry is cursed to always fall short of its mark. Poetry is an ideal, and poems are real, and what is real is often problematic. So if you say you hate poetry, what you actually hate is perhaps not so much the words on the page and their particular combination, as the fact that poetry always forces us to confront the innate banality of human expression. It is a thesis that Lerner conveys with humor and grace and a superb ear toward the truly special moments that we experience when we encounter poetry.

So I recommend that you go read the book, particularly if you (like me) feel a certain ambivalence toward poetry in general. But in the meantime, here is a little bibliography (with spare annotation) because I especially enjoyed making a mental map of the poets and essayists that Lerner mentions. It’s always fun to see who exactly is floating around inside the head of a writer.

Beginning with the famous line: “I, too, dislike it” Lerner initiates his reflections on our hatred of the genre with an amusing tale of his choosing to memorize Marianne Moore’s “Poetry” (the 1967 version) in school.

The 7th century Caedmon (as read by Allen Grossman) is the first known poet in the English language, who, according to legend, was gifted the ability to praise God in song by an angel appearing in a dream. Allen Grossman draws from this story in his poem “The Caedmon Room” and in his 1983 essay “My Caedmon: Thinking about Poetic Vocation.” (Note: These pieces are not mentioned by name, but this is where he takes his observations about Caedmon from.)

The Republic by Plato, of course. Wherein the infamous argument is made that poets should be expelled from the Republic because they cannot write of truth but only of their imaginings.

The Defense of Poesy by Philip Sidney, Elizabethan poet and defender of the art, in which the author claims that poetry is superior to philosophy and history in that it elicits emotion.

Percy Bysshe Shelley, the one and only, who writes that “the most glorious poetry that has ever been communicated to the world is probably a feeble shadow of the original conception of the poet.” It’s an idea that is essential to Lerner’s own theory of poetry, concisely portraying the frustration with poetry’s infinite potential and finite effects.

Arthur Rimbaud and George Oppen: two famous poetic quitters who are also, according to Lerner, perennially popular among budding poets because they embody the vocation of the poet while shrugging off the burden of actual poetry.

Pegasus Descending, edited by Keith and Rosemarie Waldrop, is an “anthology of truly abysmal poetry” that I cannot wait to acquire. Most importantly, it contains a poem called “The Tay Bridge Disaster” by 19th century Scottish writer William Topaz McGonagall, with which Lerner has the proverbial field day.

“Ode on a Grecian Urn” by John Keats contains the helpful line “Heard melodies are sweet, but those unheard/Are sweeter,” one of many examples in which a poet evokes the potential poem (or ‘virtual poem,’ after Grossman,) that cannot be realized.

Emily Dickinson’s “I Dwell in Possibility–“ is another such example of the poet’s emphasizing of the potential rather than the actual. Poem for Dickinson – and perhaps for us all – is Possibility, as opposed to Prose and definiteness.

Pegasus Descending, edited by Keith and Rosemarie Waldrop, is an “anthology of truly abysmal poetry” that I cannot wait to acquire. Most importantly, it contains a poem called “The Tay Bridge Disaster” by 19th century Scottish writer William Topaz McGonagall, with which Lerner has the proverbial field day.

“Ode on a Grecian Urn” by John Keats contains the helpful line “Heard melodies are sweet, but those unheard/Are sweeter,” one of many examples in which a poet evokes the potential poem (or ‘virtual poem,’ after Grossman,) that cannot be realized.

Emily Dickinson’s “I Dwell in Possibility–“ is another such example of the poet’s emphasizing of the potential rather than the actual. Poem for Dickinson – and perhaps for us all – is Possibility, as opposed to Prose and definiteness.

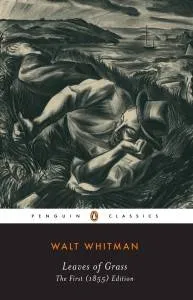

Walt Whitman’s Leaves of Grass (see particularly “Song of Myself”) is an important part of Lerner’s thinking. One of the reasons Whitman is so lauded as a poet (despite our collective hatred of poetry) is that he stands simultaneously for individuality and collectivity. (This has everything to do with the state of a secular, democratic nation in the mid-19th century.)

Unfortunately this is a bit of a problem considering that he – unlike much of America at that time and henceforth – is a white male (re: not exactly a universal figure…). This general problematic is brought about in the totally fantastic essay “On Whiteness and The Racial Imaginary” by Claudia Rankine and Beth Loffreda that Lerner wisely cites.

Walt Whitman’s Leaves of Grass (see particularly “Song of Myself”) is an important part of Lerner’s thinking. One of the reasons Whitman is so lauded as a poet (despite our collective hatred of poetry) is that he stands simultaneously for individuality and collectivity. (This has everything to do with the state of a secular, democratic nation in the mid-19th century.)

Unfortunately this is a bit of a problem considering that he – unlike much of America at that time and henceforth – is a white male (re: not exactly a universal figure…). This general problematic is brought about in the totally fantastic essay “On Whiteness and The Racial Imaginary” by Claudia Rankine and Beth Loffreda that Lerner wisely cites.

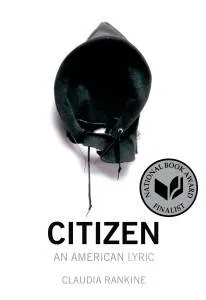

Rankine’s Don’t Let Me Be Lonely: An American Lyric and Citizen: An American Lyric also feature prominently toward the end of the book. According to Lerner, her work explores the deeply personal experience of being depersonalized (as an African-American woman living in the contemporary USA). In some way, this seems to adapt the Whitmanian individual/collective to a world where the universal cannot be represented by white males.

I’m leaving out a few pieces and many names simply for the sake of brevity. But above all, to accompany the essay, I would recommend reading the essays of Allen Grossman, whose figure haunts the book in a significant way. Indeed, Grossman’s death (in 2014) is written into the essay itself, with simple and stark emotion that is quite moving, and appropriately so for a critical exploration that deals with Poetry as a life-or-death praxis that means to confront and understand the transcendent properties of human existence.

Rankine’s Don’t Let Me Be Lonely: An American Lyric and Citizen: An American Lyric also feature prominently toward the end of the book. According to Lerner, her work explores the deeply personal experience of being depersonalized (as an African-American woman living in the contemporary USA). In some way, this seems to adapt the Whitmanian individual/collective to a world where the universal cannot be represented by white males.

I’m leaving out a few pieces and many names simply for the sake of brevity. But above all, to accompany the essay, I would recommend reading the essays of Allen Grossman, whose figure haunts the book in a significant way. Indeed, Grossman’s death (in 2014) is written into the essay itself, with simple and stark emotion that is quite moving, and appropriately so for a critical exploration that deals with Poetry as a life-or-death praxis that means to confront and understand the transcendent properties of human existence.