THE GIRL WHO DRANK THE MOON Is About Questioning the Status Quo

Content Note: discussion of book spoilers, as well as abduction and abuse in fiction.

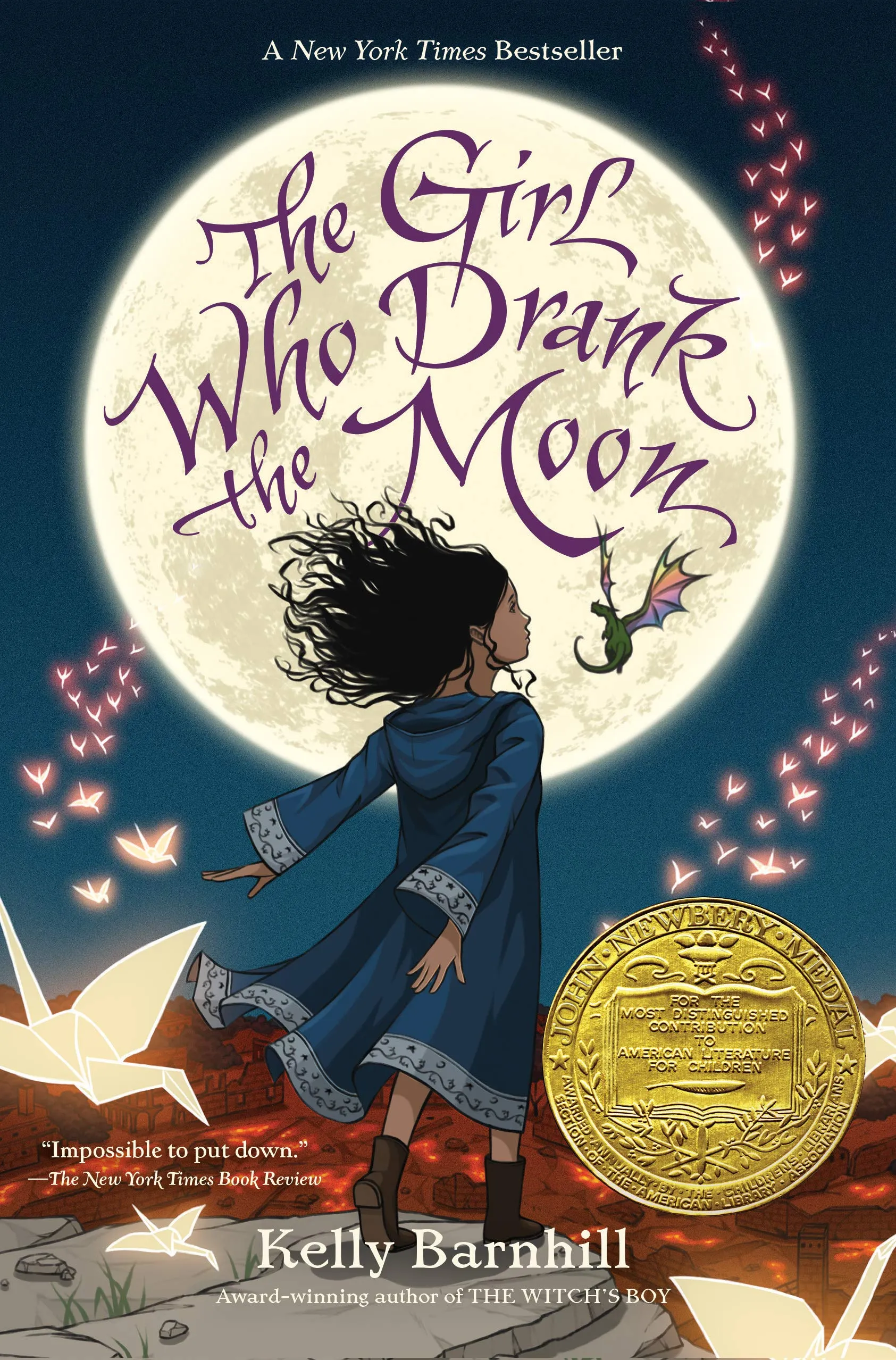

In fantasies with great worldbuilding, lore is the tip of the iceberg, hinting at a lived-in world. Magical settings have a unique ability to clarify and question ideologies, without muddling issues by critiquing any real society. The Girl Who Drank the Moon, the 2016 Newbery Medal–winning middle grade book by Kelly Barnhill, shows characters bravely challenging the status quo. Diana Wagman’s 2016 New York Times review included questioning the status quo among its many possible lessons. Broadly, the status quo means the current situation. In an unjust society, it can become the circular lie that life must be this way because it’s always been this way.

In the book, each year, the Protectorate’s citizens “sacrifice” their newest baby to the evil witch. The Protectorate’s elders abduct babies from their families, then abandon them to die in the forest. No one knows why the witch demands babies or what she does to them. No one questions this belief, either, assuming the annual sacrifice is necessary for their society to function. Stories about the witch, presented as true, blame her for everything from infanticide to pollution. These stories scare and control kids, but more insidiously, they indoctrinate children, discouraging them from second-guessing authority.

The narrative soon gives us both sides of the story. The witch, Xan, is not evil at all. She’s baffled to find babies abandoned near her doorstep every year. She always feeds them starlight, making them into Star Children, and finds loving adoptive families for them. When she accidentally feeds one baby moonlight instead of starlight, the child, Luna, becomes incredibly powerful. Xan adopts Luna, who will someday become the next witch.

Luna’s birth mom defies tradition and the elders by cursing and threatening them: “You cannot have her” (7). Unlike most parents in the Protectorate, she doesn’t accept the sacrifice as inevitable. The elders act as if her reaction to them taking her daughter is somehow irrational or “hysterical.”

Oppression doesn’t just happen. Instead, powerful people often maintain their dominance through violence, lies, and propaganda while pretending this is just the way things are. The elders might be utilitarians, trying to justify their actions as the greatest good for the greatest number of people. Or maybe they’re cynical and self-serving. The rulers of the Protectorate use both systemic oppression and interpersonal abuse to control people who refuse to conform.

After the elders abduct Luna, her birth mother is called “the Madwoman” and imprisoned in a tower. The Sisters of the Star, keepers of the Protectorate’s knowledge, tell her, “Your madness is getting worse…You never had a baby.” (249) Gaslighting, an abuse tactic that makes victims question themselves and reality, is an over- and misused term. However, this is a perfect example. They use her mental illness to make her question every aspect of her life. Whether her mental illness is genetic, from her trauma, or both, is irrelevant. This is an ableist, sexist, murderous society that weaponizes a mother’s grief against her.

Antain, Grand Elder Gherland’s nephew, witnessed Luna’s abduction in horror. As a teen, Antain was supposed to be an Elder-in-Training. His family is disappointed in him when he questions their customs and rejects the privileges they enjoy. Years later, when Antain and his wife, Ethyne, realize their baby will be that year’s sacrifice, Antain vows to kill the witch himself.

Ethyne and Antain gradually piece together who is controlling them and why.

“A story can tell the truth, she knew, but a story can also lie. Stories can bend and twist and obfuscate. Controlling stories is power indeed. And who would benefit most from such a power?” (309) Ideology has narratives — sometimes false ones to benefit certain people and marginalize others. These questions and ideas may seem obvious to adults, but the book illustrates abstract ideas for kids in a concrete, entertaining story.

Indoctrination can be subtle. Prejudices may be unconscious or taken for granted. The elders and the Sisters shift blame from themselves, scapegoating Xan. Diana Wagman wrote in her NYT review that children may find deeper messages in The Girl Who Drank the Moon years after first reading it. I agree, but I’m not a parent, teacher, or the target age for middle grade books. But I do remember the books I read at age 10 or 11, like Lois Lowry’s The Giver, that encouraged me to ask similar questions, even back then. Good stories can help readers of any age reexamine why they believe what they do or imagine change.

Further reading on middle grade books and middle grade fantasy: