Spider-Man Vs. Mental Health: How Our Heroes (Don’t) Cope with Trauma

Let me start this essay with something less than bookish: a jar of pizza sauce.

Like many people, I have trouble opening jars. I do, however, own a handy-dandy jar opener. It consists of a thick rubber band looped through a plastic handle. All I have to do is fit the band around the jar’s lid, pull, and voila. Open jar. Now I can make pizza bagels.

Sometimes I feel like a wimp for using this device. Isn’t it cheating? Shouldn’t I try harder to open a jar the “normal” way, even if it means making my hands hurt and I probably won’t succeed?

Wait a minute. How is preventing unnecessary pain “cheating?” And what’s all this got to do with Spider-Man?

Part of what we like about superheroes is their perseverance. No matter how high the odds are stacked against them, superheroes keep pushing forward, determined to do the right thing even if it costs them dearly. This may be a great character trait when you face imminent death on a daily basis, and it can certainly inspire readers to work harder and help others in real life.

But does it come with a downside? How does it affect them during less urgent moments? Can too much perseverance end up backfiring and doing more harm than good? The essays in Spider-Man Psychology: Untangling Webs, edited by Travis Langley and Alex Langley, offer insights into just that topic, among others.

Up to Eleven

Many people, including some of the authors in this collection, rightfully praise Spider-Man for his refusal to give up, ever. They specifically cite the scene in Amazing Spider-Man #33, in which our hero gets himself out from under “tons of fallen steel” in order to deliver medicine that might save his Aunt May. After that, he still has to fight his way through a whole army of Doctor Octopus’s goons with an injured leg.

In a situation like this, it makes sense for Peter to push himself so hard: he’s alone, it’s an emergency, and someone he loves will die if he doesn’t push. Unfortunately, for many heroes, “pushing too hard” is the norm, even when circumstances are not so dire. Iron Man has been known to have a heart attack and then get back in the armor the very same day. And the entire Batman family seems to be allergic to doctors.

There’s the sense that, because they’re a hero, they have to be better than everyone else. As Spidey puts it during his fight with Ock’s goons, “What if my leg is injured? What if they are more rested? They’re just a gang of mangy crooks — but I’m Spider-Man!”

Several essays in the Langleys’ book suggest that Spidey’s self-destructive tendencies are the result of survivor guilt. Peter only became a hero after he selfishly chose to let a thief escape, giving that thief the chance to murder Peter’s Uncle Ben that same night. As he’s psyching himself up to take action in Amazing Spider-Man #33, you can see that he is still haunted by this decision, and he uses that guilt just as much as he uses his love for Aunt May to drive his escape.

Early trauma is by no means a problem unique to Spider-Man: most superheroes suffered the loss of a parent or parents, domestic abuse, substance abuse in the home, or another adverse childhood experience (ACE) that could have shattered their sense of security and trust, leading to the lone wolf behavior we so often see in our heroes.

Compulsion. Guilt. These are not things we should be seeking to emulate. Spidey is certainly a great hero, but not because he is on “a lifelong treadmill of being controlled by his sense of responsibility to others.”

If you were to purposely cause pain to another person just to show how tough you are, most people would consider you a bad guy. But if you purposely cause pain to yourself for the same purpose, all of a sudden you’re a macho man deserving of admiration and blockbuster action movies.

Use Your Words

Is there anything Spidey and similarly self-sacrificing heroes could do to wage a healthier war against crime? Absolutely! Unfortunately, it is something that heroes are universally bad at: honest communication.

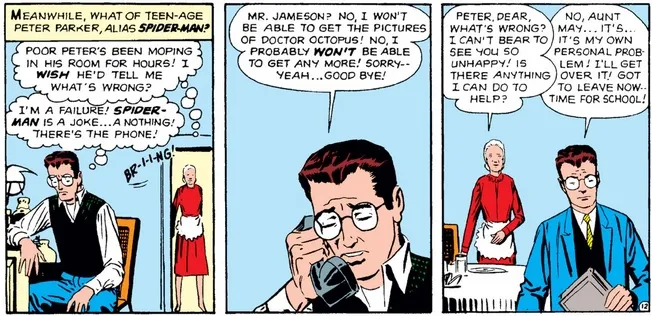

In her essay “Finding Your Inner Superhero: Adolescent Moral Identity Development,” Apryl Alexander states that “Peter’s choice to isolate himself as Spider-Man also isolates him from typical sources of guidance,” in particular his Aunt May, his legal guardian. Whereas most kids can turn to a mentor — whether it be a parent, guardian, teacher, religious leader, or someone else — for advice when times get tough, Peter can’t, because doing so would jeopardize his secret identity and, by extension, May’s life.

As you may imagine, this causes problems for young Peter, in both of his identities. Having a source of advice and support is a critical ingredient for growing into a well-adjusted adult. Denying himself that, even for a good cause, leads to feelings of inadequacy and isolation and a lack of perspective that further harm his mental state.

In “Behind the Mask: The Web of Loneliness,” Janina Scarlet and Jenna Busch write that “many people are deemed to be ‘strong’ for not showing emotions and are praised for wearing metaphorical ‘I’m fine’ masks,” even though humans are “wired for belonging” and can only thrive when in open, honest communication with other human beings.

If you were to purposely cause pain to another person just to show how tough you are, most people would consider you a bad guy. But if you purposely cause pain to yourself for the same purpose, all of a sudden you’re a macho man deserving of admiration and blockbuster action movies.

This attitude is not just stupid but also ableist. The idea that you can only be heroic, admired, and accomplished by pushing yourself beyond your limits is unhealthy and unsustainable — and it implies that anyone who fails to do so is more akin to the “98-pound weakling” used to appear in body-building comic book ads.

And yet, Spidey seems incapable of breaking free of such harmful behavioral patterns. Brittani Oliver Sillas-Navarro’s essay “Attachment and Adverse Childhood Experiences” says that we can blame his lack of communication skills — much like his tendency to overextend himself — on his traumatic past: “Had [Peter] had a different trajectory in his experiences, he may have had an opportunity to feel more emboldened to be more transparent…interpersonally about his trial[s] and tribulations.”

A Few More Words

Please don’t take this criticism to mean that I think superheroes must all be paragons of mental health and perfect role models for readers. They are fictional characters. They’d be pretty dull if they had no flaws. And if you do want to view superheroes as role models, you can learn just as much from what they do wrong as what they do right.

Are there some circumstances where people — both in fiction and in real life — really do have to tough it out, even at the expense of their well-being? Sure. But if you’ve got friends, family, or even acquaintances who are ready, willing, and able to lend you a hand, that is not that type of situation. It’s okay to ask for back-up. To stay in bed until your wounds heal. To use the stinkin’ jar opener.

For more superhero psychology, check out my article on mental illness in Batman comics!