Is There Worth In Shock Value?

José Saramago is one of Portugal’s most prominent writers, and he came to international attention after having won the Nobel prize for literature in 1998. As per my understanding, and memory, he also pretty much came to the general attention of his home country after that particular win, especially outside of Portugal’s literary community.

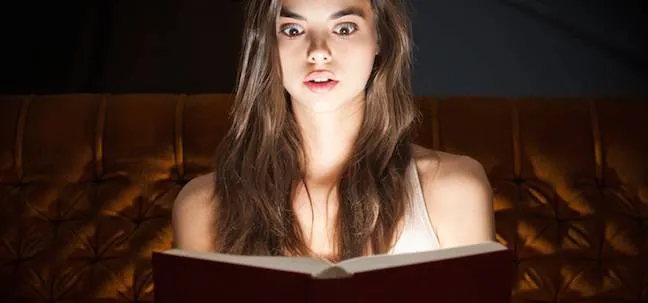

I was 18 when I decided to read him for the first time, and I was advised to read The Gospel According To Jesus Christ, which many still consider one of his best works of fiction. I borrowed the book from my local library, and I ended up returning it to the library’s shelf unread. Well, mostly unread.

The book is a reimagination of the life of Jesus Christ, and it starts with quite the scene: Mary and Joseph in bed, early in the day, having sex. The sex is very matter of fact, devoid of apparent emotion, straight to business kinda sex. Joseph finishes and he immediately gets up, out of bed, and on to take care of other, more pressing businesses.

There is no soul connection, no cuddling after, no looking into each other’s eyes and declaring unconditional love, or any love whatsoever, for that matter; as much as the idea of unconditional love irks me, it seemed at the time adequate for the parents of the messiah. Also, I used to read a lot of fade-to-black-when-there’s-a-sex-scene romances at the time, so I had some standards. I’m not saying the standards were good or bad, but they were there.

I am not religious anymore, but I was at 18. I didn’t like going to church nor did I take part in any other activity pertinent to religion. But like Smash Mouth, I was a believer, and being raised in a religious — and rather conservative — environment, I had certain ideas of what was okay to say and do (and write) and not. That scene shocked me, and I could not read beyond those first two pages.

When others gave up on Saramago because of his incredibly long sentences and lack of punctuation — it’s his signature style — I gave up on him because he dared to image Joseph and Mary having practical, patriarchal morning sex.

I haven’t yet gotten back to that book, not because of that scene — I would certainly be able to stomach it easily now, and even laugh at Saramago’s audacity of writing that in a prude society like the Portuguese one was in 1998, which has very easily rejected his attempts at challenging the church. I simply still haven’t gotten around to buying the book yet, but it is fitting to mention Saramago’s Gospel, since reading it was the first time that, without knowing the term, I considered the concept of shock value.

In my young, religious mind, I couldn’t conceive why someone would expressly decide to include this scene in these terms in a book: open with it, even.

But as I grew older and shed most of the prejudices I was taught growing up (along with my religious upbringing), I’ve encountered similar situations a few other times, and they always leave me with a feeling of uneasiness, and questioning myself: am I being a prude, or is this scene really unnecessary? Which point is it trying to make?

The Discomfort

I moved to the Netherlands two years ago, and I’ve been working at a Dutch indie bookshop since 2020.

Marieke Lucas Rijneveld published The Discomfort Of Evening in 2018; since I didn’t grow up surrounded by Dutch literature, I’m usually curious to know how and what Dutch authors write.

There is actually one particularity I’ve considered a few times since I’ve left Portugal: there are always things imbued in a country’s culture that makes it almost impossible, as a foreigner, to catch up to said culture. I’ll never know every single small Dutch celebrity, nor will I burst out singing to the familiar Dutch hits some of my friends grew up with, stuff that comes so natural to them as breathing or eating hagelslag, because they learned about these things in the same way they learned the language: by being exposed to it since childhood. But I can try to at least become familiar with the literature scene, especially because it’s intrinsic to my job.

The Discomfort Of Evening was the first Dutch novel to win the international Booker Prize. I understand why the book became a hit, and won awards: both the plot and the writing are quite extraordinary. There is a sadness seeping from the pages, and although the narrative is clear and straightforward, a lot of it is atmosphere. A ten year old girl, a family, a lost brother. The way the family navigates away from each other consumed by the loss and the grief. It’s really, really good, and it’s based on Rijneveld’s own experience losing a sibling at that age.

Chapter 8, however, opens with a scene that disturbed me. Which is weird, because the scene isn’t exactly brutal: the little girl is constipated and her father is helping her sort it out. Now, I know what you’re thinking: they’re in the toilet, working some sort of enema. Wrong. The description continues and it is rather graphic: the child is laying on her side on the sofa, the father cutting pieces of soap and inserting them in her anus: “Before I can think about it any further, Dad has shoved the chunk of soap deep into my bum hole with his index finger”, and it continues, the scene in question alternating between what is happening, and what the child is doing to try and distract herself. This, which may seem to some rather untroubling, rattled me.

Because, you see, I wondered: why was this scene necessary? Especially told from the child’s perspective? I’ve read a few more pages and I don’t understand how relevant to the plot this was, or why the author had decided to include something so particular and, honestly, weird in the book. What was the purpose of it? I could not see it and I ended up setting the book aside.

It didn’t help that I’ve seen similar reviews regarding this book ever since: people complaining that it contains pretty shocking scenes which, while not exactly removing the value of the book as a whole, seem to be there simply to shock and disturb readers.

The Melting

A few weeks ago, in that same journey of getting to know Dutch writers, I picked up The Melting, by Lize Spit.

Spit is actually Belgian, but she writes originally in Dutch, and after finishing The Melting, I wondered: is writing to shock a Dutch literary fiction thing? Is this like much of well-known Portuguese cinema, where cursing and cheap, graphic sex scenes seem to be the norm? Is this a cultural thing? To this I have no final answer, but I’ve spoken with other (Dutch) readers who seem to share similar views on these two books.

The Melting is about a group of kids in a small town. I immediately felt affinity for the main character, who is friends with a boy whose parents own a cow farm.

I lived in a small town most of my life and, as a child, I too had a friend whose parents owned a cow farm. I used to spend entire afternoons there, helped take the cows for milking, and even learned to drive a tractor. There was a lot of the story I could relate to, and I can see how much of it rings true to a small town setting. But as the story progressed, the wilder the relationship between the main character and her two best friends — kids turning teenagers — became.

Eventually, more to the end of the book, it all turned a bit too wild to be believable. And don’t get me wrong: maybe somewhere these stories could have happened, but at several points I really thought the author had went too much over the edge. And not in an I-am-religious-and-maybe-a-bit-conservative way — I’m way past that — but more as what exactly is the purpose of all this violence in the development of the plot? And I came out empty handed.

The scenes in question did not have to be that violent, that sexual, and abusive, for the whole thing to make sense and to work. Actually, their effect was the opposite: had those scenes been less shocking, the story would have rang much more true.

This is not to say I didn’t like the book — I gave it a 4.5 star rating, and I still recommend it. It is still a fantastic piece of literature. But the half-point lost from my rating was due to the shameless use of violence. Because I still think a lot of it feels, even if it wasn’t, to have been written for pure shock value. Because shock value, very often, makes people talk, which sells. And not often enough, in my opinion, is it questioned.

A Little Life

When I first started mapping this article out, I was not going to mention A Little Life. But after accessing shock value and my relationship to the books above, I think it makes sense to bring A Little Life to the table as well.

I don’t usually enjoy long books, so I tend to choose books that are between 200 and 350 pages, but there was so much love around the internet for A Little Life back in 2015 that I ended up buying it.

To be honest, I don’t think I was aware of how many pages the book had when I picked it up: I got it for my ereader, and in the articles I read concerning it, either they didn’t mention it was a long book, or I didn’t pay attention. I remember stumbling upon it in a bookstore after having read it, and being surprised by how thick it was.

I simply picked it up and, like most people, I loved it. I cried, I looked at it with sorrow once it was finished, because that book wrecked me. But a few months later, as I was considering the book again at a distance, a few questions started to pop up. Who wrote this book? I know their name, but who are they, and what legitimacy do they have to write this particular story?

Now, I don’t necessarily agree that writers should only write their own personal experiences or identities (it should work on a case by case basis, in my opinion). Fiction serves a purpose, and it is because writers can imagine a different world and life besides their own, that we have stories. But A Little Life is a book that seems to live off only of its own tragedy.

Hanya Yanagihara is a talented writer, there is absolutely no doubt of that, but when does the tragedy surpasses itself, and become trauma-porn? Why was this author telling the story of a queer, disabled, sexually abused man, a story where there was no redemption for suffering, except a different type of tragedy?

The more I thought about this book, and why most people gushed about it, the more bothered I become. And yes, to a certain extent, it is human vulnerability — and yes, suffering — that pulls us to the page. A lot of the books I love are absolutely sad and dramatic, with no sliver of joy in them, but A Little Life went beyond what I tend to accept when it comes to someone’s imagined suffering. And yet, I gobbled it up, and only then did I wonder: where is the line between telling a good story, opening up wounds and tragedies to be seen and understood by others, and writing for shock value?

The truth is, I don’t have an answer. The line is different for everyone, and some will read the same books I have read and find them perfectly acceptable, each shocking scene absolutely relevant for the development of the plot. To me, these books become more like strangers, a story I want to detangle myself from, because they went a bit too far, a bit too deep. They touch a spot that should very well have been left alone.

No matter where our line is, it is important to keep questioning these things, to see shocking scenes — especially abusive ones — through a wider lens. Otherwise we will continue to commit the mistake of using people that are real outside of literature as a propulsion tool for the stories of others, diminishing and objectifying certain groups. When we stereotype the same communities over and over, using them as mere plot devices in fiction, and laying our own prejudices against them, many will start to believe the stereotypes to be true — and the prejudices to be justified — even outside of the fiction field.

I always take a step back to try and figure out why certain books shock me. Is it my own prejudices, like with Saramago? Or is it something outside of myself that should be questioned and addressed? Is there worth in shock value? This is an invitation to consider all this.

Here is another post written by our contributor Ashley that reflects on shock value and the sweary titles of self-help books that you may want to read next.