Sharing Our Love of Books, One Way or Another

This is a guest post by Josh Corman. Josh splits his slivers of free time between his incredibly patient wife, his wildly energetic son, the Kentucky Wildcats, and a tall stack of books. He also teaches high school English and blogs about faith, fatherhood, and culture at thethingaboutflying.com. His novels, short stories, and a memoir have appeared on his computer screen and in various desk drawers. Follow him on Twitter @JoshACorman.

My grandmother – “Nanny,” as we called her – and I had two things in common. The first was a pathological obsession with the University of Kentucky Men’s Basketball program (which we shared with more than a few other family members and friends) and the other was a love for reading (which… not so much).

Now, she’s not the person with whom I usually traded sacred favorites or to whom I gushed about my first brush with a new favorite author. She read mostly grocery store paperbacks (and continuously – she stacked them in kitchen cabinets when finished and donated a pile when she could no longer close the door) and adopted a flat, accommodating smile if I ever talked too analytically about the books I studied in college and later taught to my high school students.

But even though our reading paths rarely crossed, I did work up the courage on a couple of occasions to bring her books that I thought she might appreciate for one reason or another. The last of these was Marilynne Robinson’s Gilead. When I went to visit my grandfather after her death in early December, I noticed it on the counter, stacked atop a couple Patricia Cornwell novels. During the only conversation we ever had about the novel – a brilliant epistolary meditation on faith, grace, and family – she described it as “deep” and made a face that suggested indigestion more than revelation.

And yet.

When I think about the way she always asked if I was reading anything good at the moment, about the gifts she bought my young son – including a Nook Color (because it could “do children’s books”) and a box of abridged classics that he won’t be able to read for at least a few more years – for the few of his birthdays she lived to see, I realize how concerned she was with keeping a reading legacy alive in our family. Nanny never attended college, and she never seemed overly concerned with wider cultural overtures, but she knew what kind of a window reading could be into the world beyond her own experience, what kind of a leg up a voracious reading appetite afforded her in the day to day. Reading made her tougher, more self-assured, and more generous. And so her love of reading has become the lens through which I appreciate her most memorable attributes; I simply cannot separate her from it.

A few weeks ago my dad called and told me that my aunt was overseeing the clearing out of Nanny’s antique shop, a converted nursing home now stuffed with Amish furniture, glassware, and myriad other country relics. He said that if there was anything from the shop that I might want, I should go there to set it aside.

I piled my son into the car and drove over. When I got there, the place already looked half-empty. Crowded tables lined the walls of many of the rooms and a few of my cousins were negotiating the disassembly and removal of a couple of large items. My son tailed me from room to room, asking me with the unflagging persistence particular to three-year-olds what everything was. Meanwhile, none of the old quilts or decorative pillows or silver tea sets called my name. I mean, none of that stuff was really hers anyway, not in the family heirloom sense; she had bought it to sell it.

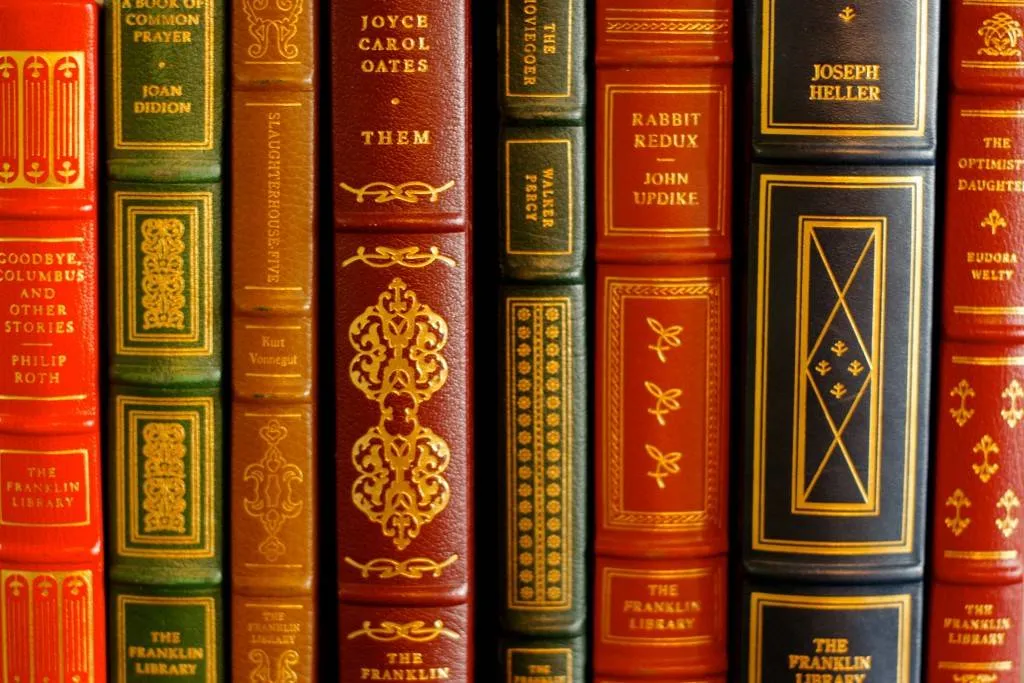

But when we came to a small room near the back of the shop, a candidate came forth. On a tall professor’s bookshelf (the kind with glass-front doors that lift out and then slide back into the shelf space), there rested a set of books, all uniformly bound in dark leather covers and printed on gold leaf pages. I squinted at the spines and saw among the titles works by Truman Capote, Tennessee Williams, Arthur Miller, Ralph Ellison, Joseph Heller, James Baldwin, Joan Didion, Joyce Carol Oates, and Norman Mailer. Aha! Here was my claim. Even though they weren’t Nanny’s books in a traditional sense, they felt more connected to my memories of her than any copper wash basin or bronze oil lamp.

I pulled some boxes from a stack near the back of the shop and began piling the books into them while my son played hide-and-seek with an old teddy bear. For no real reason at all, I slid a red volume from the shelf, a collection of Philip Roth’s stories, and flipped through the pages. My eyes stopped on the title page where, tucked behind a slip of tissue paper, Roth’s signature just sat there, acting in no way responsible for what I felt sure was an impending cardiac episode.

I sat down the Roth and picked up an Updike. It too was signed. As was the Sartre, the Vidal, and all the books by all the authors I mentioned above. Sixty in total, I would later learn, all Pulitzer Prize winners.

And there I stood, my three-and-a-half-year-old son the only witness to my silent euphoria at having discovered something about which I can only assume nobody, not even Nanny, knew. There was no price tag on the set; they were simply dressing for the shelf. A few of them had even been moved to other shelves for appearances’ sake. Some felt so stiff that I’m nearly certain they hadn’t been opened since the authors signed them.

I have no idea how those books came to rest on that shelf, but a friend of mine, who professes not to believe in coincidence, told me that she thinks that Fate had led them there and was waiting for me to collect them. And although my friend and I don’t see coincidence in quite the same way, stumbling upon these books does feel significant. They feel like a collective symbol of the idea that reading finds a way to continue its hold, in one form or another, generation after generation, the hope that our children and grandchildren will carry our love of books into the often unforeseeable future.

My son paid little attention to the books crowding his car seat on the ride home, choosing instead to occupy his imagination with a tiny plastic dinosaur, but I hope that one day they’ll catch his eye and I’ll tell him the story of their discovery and his eyes will widen at all the right moments. Mostly though, I hope that reading finds a way into his soul the way it found its way into mine, passed on by a parent, grandparent, or a teacher. Or by simple coincidence. Or even, as may be the case, by the hands of Fate.

My grandmother – “Nanny,” as we called her – and I had two things in common. The first was a pathological obsession with the University of Kentucky Men’s Basketball program (which we shared with more than a few other family members and friends) and the other was a love for reading (which… not so much).

Now, she’s not the person with whom I usually traded sacred favorites or to whom I gushed about my first brush with a new favorite author. She read mostly grocery store paperbacks (and continuously – she stacked them in kitchen cabinets when finished and donated a pile when she could no longer close the door) and adopted a flat, accommodating smile if I ever talked too analytically about the books I studied in college and later taught to my high school students.

But even though our reading paths rarely crossed, I did work up the courage on a couple of occasions to bring her books that I thought she might appreciate for one reason or another. The last of these was Marilynne Robinson’s Gilead. When I went to visit my grandfather after her death in early December, I noticed it on the counter, stacked atop a couple Patricia Cornwell novels. During the only conversation we ever had about the novel – a brilliant epistolary meditation on faith, grace, and family – she described it as “deep” and made a face that suggested indigestion more than revelation.

And yet.

When I think about the way she always asked if I was reading anything good at the moment, about the gifts she bought my young son – including a Nook Color (because it could “do children’s books”) and a box of abridged classics that he won’t be able to read for at least a few more years – for the few of his birthdays she lived to see, I realize how concerned she was with keeping a reading legacy alive in our family. Nanny never attended college, and she never seemed overly concerned with wider cultural overtures, but she knew what kind of a window reading could be into the world beyond her own experience, what kind of a leg up a voracious reading appetite afforded her in the day to day. Reading made her tougher, more self-assured, and more generous. And so her love of reading has become the lens through which I appreciate her most memorable attributes; I simply cannot separate her from it.

A few weeks ago my dad called and told me that my aunt was overseeing the clearing out of Nanny’s antique shop, a converted nursing home now stuffed with Amish furniture, glassware, and myriad other country relics. He said that if there was anything from the shop that I might want, I should go there to set it aside.

I piled my son into the car and drove over. When I got there, the place already looked half-empty. Crowded tables lined the walls of many of the rooms and a few of my cousins were negotiating the disassembly and removal of a couple of large items. My son tailed me from room to room, asking me with the unflagging persistence particular to three-year-olds what everything was. Meanwhile, none of the old quilts or decorative pillows or silver tea sets called my name. I mean, none of that stuff was really hers anyway, not in the family heirloom sense; she had bought it to sell it.

But when we came to a small room near the back of the shop, a candidate came forth. On a tall professor’s bookshelf (the kind with glass-front doors that lift out and then slide back into the shelf space), there rested a set of books, all uniformly bound in dark leather covers and printed on gold leaf pages. I squinted at the spines and saw among the titles works by Truman Capote, Tennessee Williams, Arthur Miller, Ralph Ellison, Joseph Heller, James Baldwin, Joan Didion, Joyce Carol Oates, and Norman Mailer. Aha! Here was my claim. Even though they weren’t Nanny’s books in a traditional sense, they felt more connected to my memories of her than any copper wash basin or bronze oil lamp.

I pulled some boxes from a stack near the back of the shop and began piling the books into them while my son played hide-and-seek with an old teddy bear. For no real reason at all, I slid a red volume from the shelf, a collection of Philip Roth’s stories, and flipped through the pages. My eyes stopped on the title page where, tucked behind a slip of tissue paper, Roth’s signature just sat there, acting in no way responsible for what I felt sure was an impending cardiac episode.

I sat down the Roth and picked up an Updike. It too was signed. As was the Sartre, the Vidal, and all the books by all the authors I mentioned above. Sixty in total, I would later learn, all Pulitzer Prize winners.

And there I stood, my three-and-a-half-year-old son the only witness to my silent euphoria at having discovered something about which I can only assume nobody, not even Nanny, knew. There was no price tag on the set; they were simply dressing for the shelf. A few of them had even been moved to other shelves for appearances’ sake. Some felt so stiff that I’m nearly certain they hadn’t been opened since the authors signed them.

I have no idea how those books came to rest on that shelf, but a friend of mine, who professes not to believe in coincidence, told me that she thinks that Fate had led them there and was waiting for me to collect them. And although my friend and I don’t see coincidence in quite the same way, stumbling upon these books does feel significant. They feel like a collective symbol of the idea that reading finds a way to continue its hold, in one form or another, generation after generation, the hope that our children and grandchildren will carry our love of books into the often unforeseeable future.

My son paid little attention to the books crowding his car seat on the ride home, choosing instead to occupy his imagination with a tiny plastic dinosaur, but I hope that one day they’ll catch his eye and I’ll tell him the story of their discovery and his eyes will widen at all the right moments. Mostly though, I hope that reading finds a way into his soul the way it found its way into mine, passed on by a parent, grandparent, or a teacher. Or by simple coincidence. Or even, as may be the case, by the hands of Fate.

My grandmother – “Nanny,” as we called her – and I had two things in common. The first was a pathological obsession with the University of Kentucky Men’s Basketball program (which we shared with more than a few other family members and friends) and the other was a love for reading (which… not so much).

Now, she’s not the person with whom I usually traded sacred favorites or to whom I gushed about my first brush with a new favorite author. She read mostly grocery store paperbacks (and continuously – she stacked them in kitchen cabinets when finished and donated a pile when she could no longer close the door) and adopted a flat, accommodating smile if I ever talked too analytically about the books I studied in college and later taught to my high school students.

But even though our reading paths rarely crossed, I did work up the courage on a couple of occasions to bring her books that I thought she might appreciate for one reason or another. The last of these was Marilynne Robinson’s Gilead. When I went to visit my grandfather after her death in early December, I noticed it on the counter, stacked atop a couple Patricia Cornwell novels. During the only conversation we ever had about the novel – a brilliant epistolary meditation on faith, grace, and family – she described it as “deep” and made a face that suggested indigestion more than revelation.

And yet.

When I think about the way she always asked if I was reading anything good at the moment, about the gifts she bought my young son – including a Nook Color (because it could “do children’s books”) and a box of abridged classics that he won’t be able to read for at least a few more years – for the few of his birthdays she lived to see, I realize how concerned she was with keeping a reading legacy alive in our family. Nanny never attended college, and she never seemed overly concerned with wider cultural overtures, but she knew what kind of a window reading could be into the world beyond her own experience, what kind of a leg up a voracious reading appetite afforded her in the day to day. Reading made her tougher, more self-assured, and more generous. And so her love of reading has become the lens through which I appreciate her most memorable attributes; I simply cannot separate her from it.

A few weeks ago my dad called and told me that my aunt was overseeing the clearing out of Nanny’s antique shop, a converted nursing home now stuffed with Amish furniture, glassware, and myriad other country relics. He said that if there was anything from the shop that I might want, I should go there to set it aside.

I piled my son into the car and drove over. When I got there, the place already looked half-empty. Crowded tables lined the walls of many of the rooms and a few of my cousins were negotiating the disassembly and removal of a couple of large items. My son tailed me from room to room, asking me with the unflagging persistence particular to three-year-olds what everything was. Meanwhile, none of the old quilts or decorative pillows or silver tea sets called my name. I mean, none of that stuff was really hers anyway, not in the family heirloom sense; she had bought it to sell it.

But when we came to a small room near the back of the shop, a candidate came forth. On a tall professor’s bookshelf (the kind with glass-front doors that lift out and then slide back into the shelf space), there rested a set of books, all uniformly bound in dark leather covers and printed on gold leaf pages. I squinted at the spines and saw among the titles works by Truman Capote, Tennessee Williams, Arthur Miller, Ralph Ellison, Joseph Heller, James Baldwin, Joan Didion, Joyce Carol Oates, and Norman Mailer. Aha! Here was my claim. Even though they weren’t Nanny’s books in a traditional sense, they felt more connected to my memories of her than any copper wash basin or bronze oil lamp.

I pulled some boxes from a stack near the back of the shop and began piling the books into them while my son played hide-and-seek with an old teddy bear. For no real reason at all, I slid a red volume from the shelf, a collection of Philip Roth’s stories, and flipped through the pages. My eyes stopped on the title page where, tucked behind a slip of tissue paper, Roth’s signature just sat there, acting in no way responsible for what I felt sure was an impending cardiac episode.

I sat down the Roth and picked up an Updike. It too was signed. As was the Sartre, the Vidal, and all the books by all the authors I mentioned above. Sixty in total, I would later learn, all Pulitzer Prize winners.

And there I stood, my three-and-a-half-year-old son the only witness to my silent euphoria at having discovered something about which I can only assume nobody, not even Nanny, knew. There was no price tag on the set; they were simply dressing for the shelf. A few of them had even been moved to other shelves for appearances’ sake. Some felt so stiff that I’m nearly certain they hadn’t been opened since the authors signed them.

I have no idea how those books came to rest on that shelf, but a friend of mine, who professes not to believe in coincidence, told me that she thinks that Fate had led them there and was waiting for me to collect them. And although my friend and I don’t see coincidence in quite the same way, stumbling upon these books does feel significant. They feel like a collective symbol of the idea that reading finds a way to continue its hold, in one form or another, generation after generation, the hope that our children and grandchildren will carry our love of books into the often unforeseeable future.

My son paid little attention to the books crowding his car seat on the ride home, choosing instead to occupy his imagination with a tiny plastic dinosaur, but I hope that one day they’ll catch his eye and I’ll tell him the story of their discovery and his eyes will widen at all the right moments. Mostly though, I hope that reading finds a way into his soul the way it found its way into mine, passed on by a parent, grandparent, or a teacher. Or by simple coincidence. Or even, as may be the case, by the hands of Fate.

My grandmother – “Nanny,” as we called her – and I had two things in common. The first was a pathological obsession with the University of Kentucky Men’s Basketball program (which we shared with more than a few other family members and friends) and the other was a love for reading (which… not so much).

Now, she’s not the person with whom I usually traded sacred favorites or to whom I gushed about my first brush with a new favorite author. She read mostly grocery store paperbacks (and continuously – she stacked them in kitchen cabinets when finished and donated a pile when she could no longer close the door) and adopted a flat, accommodating smile if I ever talked too analytically about the books I studied in college and later taught to my high school students.

But even though our reading paths rarely crossed, I did work up the courage on a couple of occasions to bring her books that I thought she might appreciate for one reason or another. The last of these was Marilynne Robinson’s Gilead. When I went to visit my grandfather after her death in early December, I noticed it on the counter, stacked atop a couple Patricia Cornwell novels. During the only conversation we ever had about the novel – a brilliant epistolary meditation on faith, grace, and family – she described it as “deep” and made a face that suggested indigestion more than revelation.

And yet.

When I think about the way she always asked if I was reading anything good at the moment, about the gifts she bought my young son – including a Nook Color (because it could “do children’s books”) and a box of abridged classics that he won’t be able to read for at least a few more years – for the few of his birthdays she lived to see, I realize how concerned she was with keeping a reading legacy alive in our family. Nanny never attended college, and she never seemed overly concerned with wider cultural overtures, but she knew what kind of a window reading could be into the world beyond her own experience, what kind of a leg up a voracious reading appetite afforded her in the day to day. Reading made her tougher, more self-assured, and more generous. And so her love of reading has become the lens through which I appreciate her most memorable attributes; I simply cannot separate her from it.

A few weeks ago my dad called and told me that my aunt was overseeing the clearing out of Nanny’s antique shop, a converted nursing home now stuffed with Amish furniture, glassware, and myriad other country relics. He said that if there was anything from the shop that I might want, I should go there to set it aside.

I piled my son into the car and drove over. When I got there, the place already looked half-empty. Crowded tables lined the walls of many of the rooms and a few of my cousins were negotiating the disassembly and removal of a couple of large items. My son tailed me from room to room, asking me with the unflagging persistence particular to three-year-olds what everything was. Meanwhile, none of the old quilts or decorative pillows or silver tea sets called my name. I mean, none of that stuff was really hers anyway, not in the family heirloom sense; she had bought it to sell it.

But when we came to a small room near the back of the shop, a candidate came forth. On a tall professor’s bookshelf (the kind with glass-front doors that lift out and then slide back into the shelf space), there rested a set of books, all uniformly bound in dark leather covers and printed on gold leaf pages. I squinted at the spines and saw among the titles works by Truman Capote, Tennessee Williams, Arthur Miller, Ralph Ellison, Joseph Heller, James Baldwin, Joan Didion, Joyce Carol Oates, and Norman Mailer. Aha! Here was my claim. Even though they weren’t Nanny’s books in a traditional sense, they felt more connected to my memories of her than any copper wash basin or bronze oil lamp.

I pulled some boxes from a stack near the back of the shop and began piling the books into them while my son played hide-and-seek with an old teddy bear. For no real reason at all, I slid a red volume from the shelf, a collection of Philip Roth’s stories, and flipped through the pages. My eyes stopped on the title page where, tucked behind a slip of tissue paper, Roth’s signature just sat there, acting in no way responsible for what I felt sure was an impending cardiac episode.

I sat down the Roth and picked up an Updike. It too was signed. As was the Sartre, the Vidal, and all the books by all the authors I mentioned above. Sixty in total, I would later learn, all Pulitzer Prize winners.

And there I stood, my three-and-a-half-year-old son the only witness to my silent euphoria at having discovered something about which I can only assume nobody, not even Nanny, knew. There was no price tag on the set; they were simply dressing for the shelf. A few of them had even been moved to other shelves for appearances’ sake. Some felt so stiff that I’m nearly certain they hadn’t been opened since the authors signed them.

I have no idea how those books came to rest on that shelf, but a friend of mine, who professes not to believe in coincidence, told me that she thinks that Fate had led them there and was waiting for me to collect them. And although my friend and I don’t see coincidence in quite the same way, stumbling upon these books does feel significant. They feel like a collective symbol of the idea that reading finds a way to continue its hold, in one form or another, generation after generation, the hope that our children and grandchildren will carry our love of books into the often unforeseeable future.

My son paid little attention to the books crowding his car seat on the ride home, choosing instead to occupy his imagination with a tiny plastic dinosaur, but I hope that one day they’ll catch his eye and I’ll tell him the story of their discovery and his eyes will widen at all the right moments. Mostly though, I hope that reading finds a way into his soul the way it found its way into mine, passed on by a parent, grandparent, or a teacher. Or by simple coincidence. Or even, as may be the case, by the hands of Fate.