Reading Pathways: Beyond the Politics – Orhan Pamuk

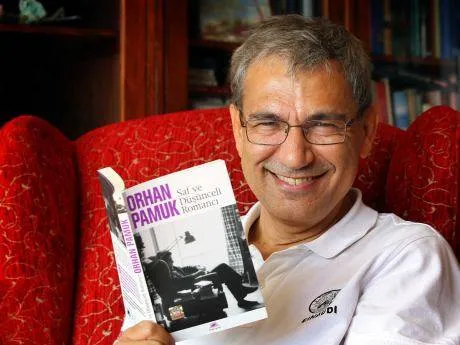

In the early 2000s, Orhan Pamuk was a established and respected writer, both in his home country and internationally. But what unfortunately brought him to widespread notice was when he became something of a cause celebre in 2005 after giving an interview to a Swiss magazine in which he dared to speak of the Armenian genocide as a fact. This was enough for him to be sued by a lawyer back home for “insulting Turkishness” (Turkey still does not officially recognize that a genocide occurred). The outrage was swift and widespread- and was unfortunately the way that many readers, like myself, became aware of his work for the first time.

However, please let me assure you, dear readers, that if my interest in him started out as political, it didn’t end that way. Pamuk is a fascinating writer who is interested in many themes on some occasions, but in two, always and ever. The first is his depiction of his inner battle between his and his country’s “Western” and “Eastern” identities, and all the anxieties, tragedies and strange beauties that come along with being a society of crossroads and change. The second, in part inspired by this, is his constant, Proustian sense of nostalgia and loss, and being forever in search of lost time that is, affectingly, never quite gone.

If you weren’t quite sure if there was anything behind the headlines and politics with Pamuk, or if you weren’t quite sure he deserved that Nobel for literary rather than political reasons, please, please let these three books, which I recommend reading in the below order, convince you that he absolutely did:

Istanbul: Memories and The City

This is the book that initially hooked me. It is a biography-cum-portrait of a city that chronicles Pamuk’s over fifty years of residence in Istanbul, where he still lives in the same house where he was born. It simultaneously gives us Pamuk’s memories and personal history as it develops over the back half of the twentieth century, intertwined with the history of the city’s somewhat confused, surreal progress as a forcibly modernized country (a process that began under Turkey’s founder, Kemal Ataturk), still encumbered, literally and figuratively, with centuries of past history that was, almost overnight, seemingly made obsolete. He is the sort of person whose knowledge intentionally goes deep and narrow- and what a deep, enthralling well it is.

This is a whole different animal. This book will tell you it is a murder mystery set in 16th century Istanbul, focusing especially on some of the meticulous artisans of the city and their families. But in actuality it is an exploration of the many different “perspectives” that make up the city- some of which are human, some of which are decidedly more metaphoric in nature (a coin, a corpse, Satan and the color red all get to have their say on events). It is a disorienting tapestry of many colors that articulates deep anxiety about the meaning of identity and self-hood, a lingering and mixed sadness for a lost history that could never be really reckoned with after the establishment of modernized Turkey, and what it is like to live in a society where you are never quite able to speak with your own voice. The prose draws a bit from magical realism, more than a bit from experimental European traditions, and, as ever, from his own deep love of his complex, ever-changing city.

This book is arguably Pamuk’s most directly political, and the least about his beloved Istanbul, which is perhaps why some readers find it the most dense. It centers on the journey of the poet Ka, who is visiting the city of Kars, a remote city in the Anatolian interior. He is drawn there to cover a recent spate of suicides among young girls. He then proceeds to encounter the full range of political, intellectual and societal possibilities of Turkey, in a plot that seems to become simultaneously more absurdist and more realistically possible with every passing minute. power derives from a discussion that is unfortunately still all too relevant these days: of the very real and every-day effects of the longing for an identity, as well as the long-term mental and emotional damage that comes along with living life as a minority in a dominant culture that differs from yours. Pamuk said in his Nobel acceptance speech that he, in part, writes to understand why he is so “very, very angry” at the world- this is perhaps his most clearly articulated vision of why.

So really. Please. Look beyond the politics, go beyond the controversy and even the Nobel- the books themselves are reason enough to lose yourself in Pamuk’s gorgeous, tortured, nostalgic world.