Turning the Page: On Publishing’s Controversies and Challenges

I should preface this by saying that I watch publishing as an enthusiastic outsider; I don’t work in the industry. Everything here is just my opinion, but I can’t be the only one who’s noticed the climbing rates of controversies in publishing.

A hundred years ago, a publishing controversy was the sort of thing that happened when people got a bit too excited about love scenes in novels. Times have really changed — these days, a sexy novel wouldn’t raise many eyebrows. Rock on, Jilly Cooper.

Publishing has a golden sort of veneer to it, a legacy perhaps of the hundreds of years of book and pamphlet publishing by community gatekeepers and tastemakers. In the new social media world where people are highly engaged and knowledgeable, that veneer has started to slip a bit, and a previously very opaque industry has seen some light chip in.

As there are more calls for transparency in decision making and a commitment to equality in practice, there are key questions about the nature of gatekeeping, the jurisdictions of storytelling, and the rights of an artist to make art.

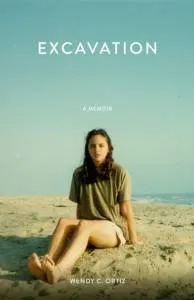

Some of the recent publishing controversies have been about writers and the stories they’re telling. When My Dark Vanessa by Kate Elizabeth Russell was published following a seven figure advance and huge publicity train, Latina author Wendy C Ortiz noted similarities between it and her 2014 memoir Excavation. In the end, Russell felt compelled to put a statement on her website noting that the book had relevance to her own younger experiences. Should any woman, ever, feel compelled to justify themself like Russell did? And should a white author receive such a large advance compared to a Latina author, when the subject matter is similar?

When American Dirt by Jeanine Cummins was published, book lovers challenged it for stereotypes and appropriation, as the author herself wasn’t Mexican; American Dirt is the story of a Mexican woman’s journey to the border with her son. Though it is a work of fiction, the furore around the book contributed to the ongoing debate about who can tell what stories. To be honest, some of this might have seemed less offensive had the publisher not used barbed-wire centrepieces at a bookseller dinner. Adding insult to injury, they noted that Cummins’s husband was an undocumented migrant, as though this would help; Cummins’s husband is Irish.

It’s not just about ‘who can tell what stories’, though. Sometimes it’s about ‘who told that story first, and did someone copy it?’ Jojo Moyes The Giver of Stars and Kim Michele Richardson’s The Book Women of Troublesome Creek were released five months apart in 2019. Both books cover the same subject, the Pack Horse Library project in Kentucky. Richardson felt that Moyes’s book was too similar, right down to plot devices, while Moyes’s publisher told Buzzfeed that Moyes’s work was wholly original. Evidence has been collated — but I’m not sure it makes things clear cut for me even now.

Then we have the questions about basic integrity. The Woman in the Window author AJ Finn is really Dan Mallory, who was the subject of a New Yorker piece which noted a long history of strange behaviour, including fabricating cancer diagnoses, lying about having a PhD, and lying about deaths of family members who are very much still alive. This one is stranger than fiction, and Mallory has pointed to bipolar disorder for some of the stories that have come out. The book itself has also come in for claims of similarities that defy mere literary influence.

It’s not all author scandal, though. Sometimes, publishers themselves make the headlines for all the wrong reasons. In 2020, I saw tweets noting that Audible would allow readers to return books and make a new choice, for up to a year after purchase — and even if you’d read the book. I had never known about this, but I was genuinely shocked to see that when such an exchange occurred, the narrator, producer, and author of the returned audiobook lost royalties. Twelve thousand authors protested and Amazon have changed their terms, but it’s not a reverse: now, Audible pays royalties for a title returned more than seven days after purchase, which is still ridiculous. Creators should be paid for their creations: #AudibleGate rumbles on.

There have been an influx of book deals for the rich and famous, presumably because trading on their names guarantees larger readership. Well off, well known people are lower risk than first time authors with no podium. In the tense political context of the past few years, a series of right-wing politicians, transphobic commentators, and abusive personalities have surged to the spotlight with shiny book deals. Where the opacity of publishing in the old days would likely keep these hidden for too long, the cracks of transparency have enabled reading communities to push back.

Publishing has some significant problems, among them a deeply challenging commercial model in an ever-changing world. To me though, the biggest controversy lately has been #PublishingPaidMe, a hashtag started by LL McKinney to bring some transparency to the inequalities in publishing. The tag exploded, with many well-known authors chipping in to tell their advance figures. What emerged was deafening evidence that Black authors — including famous and award-winning people — earn small advances compared to white authors — among them virtual unknowns with no publishing history.

And of course, publishing doesn’t pay itself either. Insiders have told The Bookseller that low salaries of £20,000 to live in London are inaccessible to all but the richest, with partners and parents often lending and gifting money for basic life expenses. In the UK, Penguin has noted in its 2020 gender pay gap report that women earn 86p for every £1 that men earn. At HarperCollins, it’s 91p : £1 , at Bloomsbury 80p : £1.

It’s clear that publishing has a hard road ahead. The industry of gatekeepers needs to be accountable for the sustained inequality for authors. It also needs to address the ethics of its decisions around who to publish, and why. And along the way, it needs to treat its own workers better, too.